Joe had a sturdy mustache and a firm handshake. He didn’t say much to us at the airport, just loaded us into the back of his flatbed truck and gunned it. As he picked up speed, the wind cooled and whipped my hippy hair against my face. Fifteen minutes later, we were parked at the docks.

“Do either of you have a license?” Joe asked as we got down from the truck.

“I do,” Joel said.

“And you’re an American citizen?”

“Yeah.”

“You’re 21?”

“Yeah.”

Joel had just turned 21. My birthday was still two weeks away. Not that it mattered—I didn’t have a license.

“And no felonies?” Joe asked.

“I’m sorry?”

“On your record? Felonies?”

“No felonies.”

“Great,” he said. “You’ll be driving the truck then.”

We were in Cordova—an Alaskan fishing village of 2,200 people. Cordova is hemmed in on three sides by the Chugach National Forest, a temperate rainforest of 6.9 million acres (approximately the size of Haiti) with mountain peaks over 10,000 feet high. It is the snowiest place on earth. The town sits on the Prince William Sound, at the mouth of the Copper River Delta, in south-central Alaska. If you imagine Alaska as a headless, armless man with one leg (the Aleutian Islands) stretching out towards Russia, and another leg (the Inside Passage) stretching down alongside Canada, then Cordova is right in the crotch.

There’s no road linking Cordova to other settlements, but if you really want to get out, you can take the 13-mile highway to Merle K. (Mudhole) Smith Airport, where you can catch flights to Anchorage, Juneau, Seattle, and Yakutat. The closest community of comparable size is the “city” of Valdez (population 3,976), 45 miles to the northwest and a five-hour ferry ride away.

We’d come to work at Copper River Seafoods. Until that moment, it had been just a website. Thereafter, it was a mess of aluminum single-story buildings set out on weary, stained docks at the northernmost edge of Orca Inlet, from where one could glimpse a few uninhabited offshore islands. Out on the inlet, we saw dozens of bald eagles rested on pylons while hundreds more flew lazy circles overhead, staring down at the water. They were in Cordova for the same reason we were.

* * *

We had heard working at the Alaskan fish canneries was a lucrative gig. Because of the long hours and labor-friendly state laws, even incompetent morons with no work experience (like us) could supposedly make bank quickly.

Alaska has a higher minimum wage than most of the country; when we went in 2004, it was $7.15 an hour, a full two dollars higher than the federal rate. And ever since 1959—when the Last Frontier became the 49th state—Alaskan statutes have also provided universal dual-overtime protection: anyone who works more than forty hours in a week or more than eight hours in a day is entitled to time and a half.

That’s important, because salmon are migratory, and in the summer, they swarm the Alaskan coast. They do this because, like sea turtles, salmon return to their natal homes to reproduce, but for Pacific salmon born so far north, anadromous migration can only happen when their natal streams have thawed out. The fish that crowd the waterways of Alaska create a veritable traffic jam; in 2005, an estimated 222 million salmon returned to spawn in the Land of the Midnight Sun.

It’s a ton of fish in a comparably small amount of water. The fisheries catch them easily en masse, after which they need to be cleaned, packaged, and sold immediately. We figured that if we went to Alaska during the summer, we’d work 80–100-hour weeks, and then blow our money on the second half of the summer traveling across Japan.

Lots of Americans from the lower 48 have gone north to fish for money. Hillary Clinton worked at a salmon cannery in the summer of 1969, when she and some fellow Wellesley graduates went to Valdez. In an interview with Lena Dunham, she called it “a great experience for being in politics.” Modest Mouse’s lead singer Isaac Brock went as well, or, at the very least, he romanticized the idea of it enough to write a song about it. In 1997, at the age of 22 and fresh out of school, Brock wrote and recorded the salmon-canning ode “Grey Ice Water” for his group’s EP Other People’s Lives.

The word of the money up north has spread, so much so that out-of-towners now dominate the industry. According to the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development, 75% of the Alaskan seafood processing laborers between 2006 and 2011 were not Alaskan natives.

* * *

Room and board, Joe informed us, would cost $12 per day, which would be deducted from our paychecks. Alternatively, we could camp in the forest and forage for berries. We elected for the former, so Joe took us to the dorm rooms. I was to room with Mike and Alejandro; Joel was bunking with Bang-Bang.

I entered the room and threw down my belongings.

“You must be the new guy,” said a voice from the top bunk. “I’m Mike,” he said, putting down his book. He was white, thin, with wire rim glasses. He looked to be in his late twenties. The sleeping middle-aged Mexican man in the bottom bunk, I surmised, was Alejandro.

I introduced myself and we began to chat. Mike was from Oklahoma and was here “because of fucking Lisa.” His life had been a series of bad mistakes: at 17 years old, he married a stripper and then joined the Army. Lisa took his surname, became addicted to methamphetamines, wrote $13,000 in bad checks, and then left him with her debt.

“Interesting,” I said. “I’m a rising junior at Bard College.”

Alejandro awoke and groggily poured himself a glass of vodka with a splash of Gatorade. “Mexican Kool-Aid,” he told me, then said nothing else to me for the rest of the summer.

Joel came into our room a few moments later.

“Hi guys, I’m Joel. Would it be okay if I take the fourth bed in this room? My roommate is smoking crack—it’s kind of a weird scene.”

* * *

On our first day of work, we didn’t clean fish. Instead, under Joe’s instruction, we headed down to the Copper River Delta and cleaned out old water coolers with BioSol, then dumped the soap scum into the ocean. Afterwards, we went to the mess hall for dinner. It was a drab room, with cheap-looking black Formica tables. The food (salmon, potato, and some overcooked canned greens) was served from deep, disposable tin trays. We found a seat with Jamie—the administrative assistant who had handled our W-2s—and a blonde Czech man named Pavel, who offered to sell us rain jackets, yellow overalls, and secondhand rain boots.

“Do we need that stuff?” I asked him.

“Are you working at the wash tank?”

“I don’t know. Are we?” I asked.

“Have you ever worked at a fishery before?” he asked.

“You’re working at the wash tank,” Jamie said.

Pavel sold us the gear for $83 each. Between our one-way flights from Anchorage to Cordova on Alaska Airways ($100 each), the day of room and board, and the rain gear, on our first day of work, we had already dug ourselves into a sizable hole.

After dinner, Jamie, Joel, and I bought a six-pack of Bud Light ($10) and headed down to the riverbanks in the forest behind the factory. Neither Joel nor I had much experience binge drinking, and Jamie laughed when we told her we didn’t know how to shotgun beer. She busted holes in our cans for us and we downed them quickly.

“How long have you lived here?” Joel asked her.

“Man, I’m Alaskan,” Jamie said, seemingly insulted by the question. “Half Inuit. My parents are Alaskan. My grandparents: Alaskan.”

“Well, it’s very nice here,” I said.

She stared down the river.

“It’s nice, but it’s dangerous if you don’t know what you’re doing,” she said. “I don’t go into the woods without at least a .22. There are so many Kodiaks around here, and they are no joke. Honestly, it’s kind of crazy we’re here without one now.”

“What’s your long term play here?” I asked. “Do you want to be a fish factory president?” I was feeling playful. Feeling my buzz.

“I’d like to be a bush pilot. That’s what my mom did. She was such a badass. On the Fourth of July there’s a huge party, and she’d always do barrel rolls between those mountains over there,” she said, pointing at the white peaks behind us. “She’d shoot firecrackers out her open window while she did it.”

“That’s awesome,” Joel said.

“Kinda,” Jamie said. “She died in a plane crash.”

Neither of us knew what to say to that, so we all looked at the river instead. I wanted to see a salmon, to get a sense of what we’d be coming up against. Suddenly, Jamie started to laugh.

“How funny would it be,” Jamie said, “if you guys both took out your dicks and asked me to blow you?”

Joel and I laughed awkwardly. No one said anything. Jamie shotgunned a second beer.

“Alright,” she said, tossing the empty into the gravel riverbed. “Let’s get out of here.”

* * *

We woke up to shouting the next morning.

“Come on boys, get up!” Mike said.

I sat up and looked around. It was bright as always. 7:15 a.m.

“Grab some breakfast if you want any,” Mike said. “But don’t overeat. The first day on the slime line can mess people up.”

“Are we working today?” I asked.

“Oh, hell yeah,” he said. “It’s an opener!”

* * *

Commercial Fishing Periods, referred to colloquially as “openers,” are set by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG). They establish when fish can and can’t be caught, which for me and Joel meant that they were effectively determining how much money we’d be making.

Because salmon are so easy to catch when they’re spawning (i.e. just take your boat to an estuary and cast a net), the Alaska Board of Fisheries recognized the importance of regulation. Otherwise, the salmon would go extinct. So they’ve appointed seven-member panels to determine escapement goals in the various waterways where salmon run. Escapement goals are the number of fish the board wants to let through the nets upriver to spawn. In the Copper River Delta, the 2005 escapement goal was 579,000 to 779,000 salmon. The escapement goal changes from year to year. Because different salmon will run at different times of the summer, they’re allowed safe passage on-and-off throughout the season, so as to maximize genetic diversity. All the while, the ADFG uses different methods to tally how many fish have come through. In some places, they set up counting towers, where someone stands thirty feet above the river for fifteen minutes per day, counting fish. Then their bosses at the ADFG use that number to infer the day’s escapement estimate. I could not believe that some motherfucker got to stand in a tower fifteen minutes a day counting fish and that that was his job. When I heard about this, I wanted that work in Cordova—but apparently the Copper River Delta is fed by glacial melt, which means the river is clouded with silt and you can’t count fish from overhead. In Cordova, they use sonar technology to poll their fish.

Fishing outside of the “openers” is a big no-no. The Alaska Wildlife Troopers monitor the state’s waterways, and if a commercial fisherman is caught fishing illegally, he stands to lose his $300,000 fishing license. So when the ADFG announces the start of the “opener” for legal fishing, the fisheries gorge .

* * *

Joel and I geared up and headed down to the factory floor, a 5,000 square foot windowless open layout underneath rows of overhead lights. Upon arriving, we watched our fellow employees head to a variety of stations throughout the factory.

“You’re going to the wash tank,” Joe told us and led us down to a large tub of water at the end of a conveyor belt. There were three other people at the tank: Sarah, a Minnesotan in her late teens and Arnold and Donald, two cheerful Native Hawaiians in their mid-twenties.

“They’ll show you what to do,” Joe said.

The factory machines came on and greeted the room with a white hum the intensity and timbre of a waterfall.

“You’re going to teach us?” I shouted at Arnold, a fat scruffy bald man who laughed and shook his head.

“Man, it’s fish,” he said. “There’s not much to teach.”

* * *

After salmon swim out of their birth rivers and into the open ocean, they’re on the clock to eat as much food as they can. After some set period of time (1–7 years, depending on the species), the school turns around and migrates back towards its birthplace. There are five kinds of North American salmon (pink, chum, sockeye, coho, and Chinook), and out at sea they chow down eel, shrimp, fish, plankton—straight inhaling whatever they can get their mouths around, sometimes heading thousands of miles out into the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea to do so.

No one knows how they find their way home. In the 1920s, scientists believed that salmon used the water temperature as a map: follow the 40°F stream for five miles, then turn left at 44°F until home. By the 1960s that idea dropped out of fashion and the odor hypothesis was all the rage: salmon smell their way home. In the 1990s, some Japanese biologists found iron in a salmon’s brain, and the new thinking was that they were using the metal in their brains as magnetic compasses. Whatever the case may be, I sure was impressed: it was my second year in college and I still didn’t know where the gym was.

But I knew how to get to Alaska—ask mom and dad for a loan and buy a ticket to Alaska. Not as easy for my fishy friends. They had to ride currents and traverse narrow fjords on their way, past salmon sharks, killer whales, bald eagles, seals—and if they got lucky with the ADFG’s timing—past the fishing boats. There, they’d finally enter the mouths of their natal rivers, free to die on their own terms.

* * *

Joel’s ex-roommate, Bang-Bang, would meet the vessels to handle the fish. Bang-Bang was twenty-something, Cambodian, and had a closely cut head of hair. Like many of the migrants at the fishery, he spoke no English. He’d been assigned to operate the forklift. This meant that his job was to drive up to the boats, lift totes of salmon off the vessels, and bring them onto the docks, where they would be placed at the entry chutes into the factory. It was a pretty plum job as far as factory work was concerned, so it was curious that he had landed it. The other workers called him “Bang-Bang” because of his propensity for crashing the forklift.

Once the fish were deposited at the entry shoot, burly Alaskan men (the “fish pushers”) would use snow shovels to send the salmon into an automated guillotine. The fish go to market, the heads to waste (a shame, according to Jamie, who told us that fish-head soup was “fucking delightful”).

After the guillotine, the Filipinos would have their turn. A group of a half-dozen men would knife open the bellies of the fish, then pass the bleeding carcasses down to the spife (spoon-knife) men—also Filipino—who would scoop out the salmon’s internal organs and separate the egg sacs. Salmon caviar is a delicacy in Japan, so the eggs were carted off into a separate room to be handled only by the salmon roe technicians who were Japanese women. At least, that’s what we were told… but I never saw any Japanese women anywhere.

Once the fish were gutted, they were placed onto a conveyor belt (aka “the slime line”), which was run by Pavel. The salmon would be squeezed into metal separators, like hot dogs shoved into buns, their slit, bleeding bellies face up. Everyone working the slime line was Czech. The Czechs were there thanks to a legal loophole the seafood processors found in the early 1990s, a time when they were having trouble attracting employees stateside. The factories hired young Europeans on the J-1 visa, which offered work travel employment to international scholars. When the salmon descended from the ceiling rafters and landed before the young Czech scholars, they ran long vinyl-hose vacuums down the length of the fish’s slits, sucking up any blood or entrails the Filipinos had missed.

The conveyor belt lurched to the rhythm of a clock—every second, the belt ticked, the salmon moving farther down the vacuum line and away from the cutting board table. And then—splash!—they would land in the wash tank.

Donald grabbed a fish, pulled it to the surface, stuck two fingers into its neck, and pulled out its heart. He cupped some water with his free hand, rubbed blood off the fish’s scales, and tossed it to Joe’s son (Joe, Jr.), who sent it down a conveyor belt.

Reaching into the water, I was pleased by how insulated I felt. In addition to the gear that Pavel had sold us, I was wearing thermal underwear, a thermal shirt, a tee shirt, a hoodie, three pairs of socks, glove liners, heavy-duty rubber gloves, a red winter hat, and—for sanitary reasons mandated by Copper River Seafoods—a beard net.

I grabbed a fish. This was a sockeye salmon—about ten pounds. It slid about in my hand, its silver scales glinting in the overhead lights. I marveled at how little the fish smelled, and with two fingers, I reached into the gaping red hole where its head had once been. A salmon’s heart is located in its throat, just under its gill rakers. It’s not easy to remove with the spife, and it’s too wedged in to suck out with a vacuum, so the job falls to the wash tank. A trick, I quickly learned, was to use your free hand to block the coagulated blood that would sometimes spray into your face.

After Joe’s son sorted the fish for gender and species, he sent them to the Mexicans in “fresh pack” who would weigh the fish, box them on ice, and send them to the truck. When it was full, Joel—who had a driver’s license—got to leave the wash tank and drive the fish to the airport, where they would be loaded onto cargo planes and flown to restaurants in the Pacific Northwest. The salmon would sell at $25–$40 per pound.

* * *

We stopped for lunch at 12:00 p.m. They served salmon. After a thirty-minute break, I headed back to the wash tank. It was only my fourth hour into what I had intended to be a full summer of fish canning. I could feel the gears turning in my head—what had I gotten myself into? Luckily, because the task was so mindless (scoop fish, rip heart, wash scales, pass) I was able to zone out, turning myself into a mindless automaton until the work ended. By 2:30 the last of the haul had been processed.

“Come back at 3:30,” Pavel told me. “There will be plenty more then.”

Joel and I walked down to the jetty and looked out to sea. It was a beautiful clear day. Joel had only spent two-thirds of his shift at the wash tank. The rest of the time he was driving to and from the airport. I resented that he’d gotten the better job.

“It’s not better,” he said. “It’s stressful in its own way.”

“It’s better,” I grumbled.

At 3:30 p.m., we were back at work. Arnold and Donald were behaving oddly. Arnold was chipper—he splashed water on me and Joel and laughed continuously, ignoring the salmon as they fell, one at a time, tick tock, into the wash tank. Donald had taken a single salmon from the tank and stared motionless down its headless throat.

“I think they’re on meth,” Joel said to me.

“Why do you say that?”

“Because everyone here keeps trying to sell me meth.”

I reached down into the wash tank and began scooping out fish. There were parts in my body that were beginning to feel some pain now, muscles that were growing raw from the repetitive motions. When I bent down to grab a sockeye, the pain was in my spine; when I pulled it out by its neck, the pain was in my index and middle finger; and when I washed the scales with my right hand, the pain was in the left forearm that was holding the fish in place.

I reached down and pulled up a salmon and was shocked to see its liver, gallbladder, lungs, and stomach—all hanging out of the body incision. Somehow, the knifemen and the scholars had failed to clean this one properly. I dry heaved.

Arnold giggled and splashed Donald. Donald reached into the tank and began rapid-firing salmon at Joe, Jr. The Filipinos by the entry chutes were working away, shouting to one another and across the floor. Alejandro, boxing up fish, was slouched over and rocking back and forth. It occurred to me that I might be the only factory worker not on any drugs.

* * *

Dinner break was at 6:30 p.m. The sun hadn’t set but it had tucked itself behind the mountains, casting long shadows onto the docks. Joel missed the meal because he was driving the truck. I sat with Frank, a fifty-something native Alaskan who’d been working in seafood processing every summer for years.

“I’m in the Guinness Book of World Records,” he told me as I shoved food into my mouth.

“What for?” I asked.

He flashed me a grin.

“Eating the most pussy!”

Break ended. There were more sockeye salmon. At 8 p.m., it was finally over. I headed back to my room and attempted to sleep, but Alejandro was having a party with his fellow Mexicans from fresh pack. They were drinking vodka in the room and didn’t pay mind to my passive-aggressive loud sighing and tossing. It wouldn’t have mattered if they had; bald eagles were screeching outside my window. At some point, I finally drifted off.

What felt like minutes later, Mike woke me up with a gentle shake.

“Hey man,” he said. “Another boat came in. It’s time to work.”

I sat up, looked out the window to the room. It was sunny outside.

“What time is it?” I asked.

“1:00 a.m.”

“Is this overtime?” I asked as I rubbed my face to try to wake.

“No,” he said. “It’s tomorrow now.”

* * *

In 2001, Saturday Night Live did a sketch starring Will Ferrell and host Reese Witherspoon, in which Ferrell played a shipwrecked sailor rescued by Witherspoon’s mermaid. It’s love at first sight, and the duo bursts into song.

Little Mermaid: “I feel brand new!”

Sailor: “I feel so free!”

Little Mermaid: “I feel an increased flow of mucus in my fish genitalia!”

As Farrell’s sailor considers the mechanical reality of inter-species sex, Witherspoon’s mermaid—oblivious to the sailor’s queasiness—sings a tune about all the aquatic species she’s banged. “I get it on with tuna,” Witherspoon explains, then mentions that her father was a drunkard who fucked a captive halibut.

It makes for decent comedy, but it’s a scientific misrepresentation. Most species of fish—halibut, tuna, and salmon included—don’t fuck. They practice external fertilization, leaving internal fertilization (that’s science-talk for fucking) largely to reptiles and mammals. But just because salmon don’t fuck doesn’t mean they’re not crazy romantic.

Before the trip, back at Bard, I’d become obsessed with an earworm of a song, “La Petite Mort” by Erin McKeown. “La Petite Mort” which is French for “The Little Death” is a euphemism for “orgasm.” The French think that in the moment you come you lose yourself, and that that feeling of losing yourself is like dying. Romantic, right? The salmon, though, stack their sex lives and their actual deaths so close to each other that they would roll their eyes at that turn of phrase.

Soon after re-entering their natal streams, the salmon’s kidneys fail. Having come to maturity in the ocean, they can no longer ingest freshwater.

They stop eating, too—which is quite unfortunate, given the journey ahead. Salmon don’t just return to the river where they were born—they return to the same stretch of gravel. For some salmon, that means traveling more than 2,000 miles upriver: with kidney failure, without eating, swimming against the current, jumping up waterfalls, maneuvering past hundreds of famished bears awakening from hibernation … all so they can return to their spot of birth. For extra energy, the salmon digests its own body fat, then its organs—everything is expended but their reproductive junk. When the fish finally reach their old stomping grounds, the female salmon prepare redds (depressions in the gravel, which serve as nests) and the male salmon fight for breeding rights. When everyone is paired off, the couples spill their eggs and milt into the redds and then continue to honeymoon upriver, repeating their sexual outercourse every few yards, until they eventually die of exhaustion in each other’s fins.

* * *

At 3:45 a.m., Sarah left the wash tank to vomit into the trash can. I hadn’t noticed her becoming sick, largely because I wasn’t feeling so hot myself. I had ingested two little green pills, which had been gifted to me at college by a chronically ill friend. I’d thought they were muscle relaxers but I would learn later that summer that they were actually anticonvulsants (Gabitril) with a plethora of negative side effects, including: blurred vision, diarrhea, dizziness, a lack of energy, and nausea. The only thing they seemed to not do was relax muscles; my body was on fire from all the repetitive motion. I thought my low dosage was the cause of the inefficacy and attributed the negative effects to monotonous labor. I considered popping two more pills.

Donald and Arnold had slowed down. Arnold was no longer splashing, just grimacing and cleaning fish at quarterpace. Sarah did not return from her vomiting. If the cannery would have elected to give daily awards for productivity, the wash tank would not have won this day—although, by this point, I hadn’t a clue what day it was. At 4:30 a.m., we were released into the break room for fifteen minutes. I downed weak coffee and took two more pills. My colleagues smoked crack, drank Mexican Kool-Aid, ate meth, ate hydrocodone, and smoked cigarettes. No one was hiding their drug use—our employers didn’t care what drugs we were on, so long as we cleaned the fucking fish.

At 4:45 a.m. we were back at it. At 5:30 a.m., I noticed how much my hands were shaking. Then Pavel moved me from the wash tank to the slime line. I didn’t think much of the change in tasks and just stumbled without second thought to the vacuums and started sucking—Blood, guts, and salmon roe spraying up from the fish and intermittently catching me in the face. This, I imagined, was being an oral hygienist felt like. My gloved right hand, which held the slit of the salmon open as I vacuumed from my left, was covered in a transparent viscous salmon sauce that greatly reduced my dexterity. Before I knew it, I found myself crying. It was a breakdown that stunned me—I hadn’t cried for non-romantic reasons since early adolescence. But the change in routine broke me. In learning a new task, I’d been forced to be more present at the factory. In being more present, I had to acknowledge my fatigue. Pavel, perhaps moved by my tears (or perhaps just needing someone back at the wash tank), took me off the slime line at 6:30 a.m. and shoved me back to my original station. Ah, to be home again!

Breakfast was scheduled for 7:00 a.m., but we worked through the hour without stopping.

“Isn’t there supposed to be breakfast?” I asked Pavel, my voice sounding alarmingly slurred to my own ears.

“Yes,” he said, then deadpanned: “But there is fish.”

At 8:15 a.m., the last fish were cleaned and the machines went silent. Pavel told the crew that the next ship would come in at 1:00 p.m., and to be ready for work then. I stumbled to the breakfast hall, ate my salmon, then made my way back to the room and passed out immediately.

Mike woke me at 12:30 p.m. with news of more fish. I headed back to the mess hall, ate lunch, and suited back up.

* * *

Ten days later, we got our first paychecks from Copper River Seafoods. After taxes and the company deductions for my housing and food, I had netted $142.11 for a week’s worth of work. Since Joel had been driving the truck, he made a few dollars more. There were no boats coming in that day, so we didn’t have to go into work. Under raw grey skies, we headed down the pier to the liquor store where we picked up a pint of bourbon. Then we grabbed a loaf of Wonder Bread at the corner store, and walked down to the jetty. We silently sat, passing the bottle between us. After a few slugs of whiskey, we decided to punch each other repeatedly, to blow off steam.

Later that afternoon, we quit. We had heard from some of our fellow employees that Alaska was a “tip credit”-free state, which meant that we could earn the same $7.15 minimum wage at restaurants as we were earning at the factory. Back in New York, employers could legally use our tips on the ledger against the minimum wage they paid us out of pocket. Here, we’d get the full $7.15 plus whatever else customers threw our way. We decided that we’d try to get jobs at the resorts by Denali National Park.

“You’re getting out of here?” Mike asked as we packed up our stuff.

“Yeah, we’re going to make a go of it upstate,” I told him. “There’s supposed to be good money in the restaurants. You should come.”

He gave me a tight smile.

“Nah, I think when the salmon start to run around here the money might start coming in.”

Pavel agreed to buy our boots, rain jackets, and overalls for 60% of what we’d paid; he would surely sell them to the next dopes and then grab a profit. We headed out. The next boat for Valdez would be leaving in three days, on Thursday. We needed somewhere to sleep, so we took our tent out to a free camping area just outside of town that the locals called Hippie Cove.

We both felt somewhat uneasy about leaving our jobs so abruptly.

“What if we don’t get more work?” Joel asked.

“I’m sure there’ll be something,” I said. “There has to be. That’s the plan.”

“Sure,” he said. “But if there isn’t, do you think your parents would lend you money?”

“I don’t want to borrow money from my parents.”

“No, I know,” Joel said, defensively raising his hands. “But I mean, if you had to, you probably could, right? Like, it wouldn’t actually be that big of a deal.”

I didn’t say anything.

* * *

High upriver, the tiny salmon young—alevin, they’re called—hatch four months after fertilization. In the dead of dark, freezing Alaskan winter, and less than a centimeter long each and still attached to yolk sacs, they burrow down into the gravel bed of the stream. They have no gills. They have no eyes. They have no teeth. They don’t even have a digestive system. All they have are those yolk sacs, and as they consume them, they metamorphose. When the sacs finally run out, it is spring, and the fish ascend from the gravel as fry, filling their swim bladders with oxygen, beginning to search the river for food. The pink and chum salmon head right to sea as soon as they’ve left the gravel bed. Others, like the sockeye, can spend up to two years in the river, feeding on insects on the surface of the water and wading in the shallows, protected from the large predators that await them in the bay.

Sooner or later though, they must begin their migration towards the ocean. The river currents are swift, and the fry aren’t strong swimmers yet so they head downstream tail-first. Swept in the churning waters, they risk being crushed against the rocks, and the young salmon can only blindly hope they’ll make it to the deep alive.

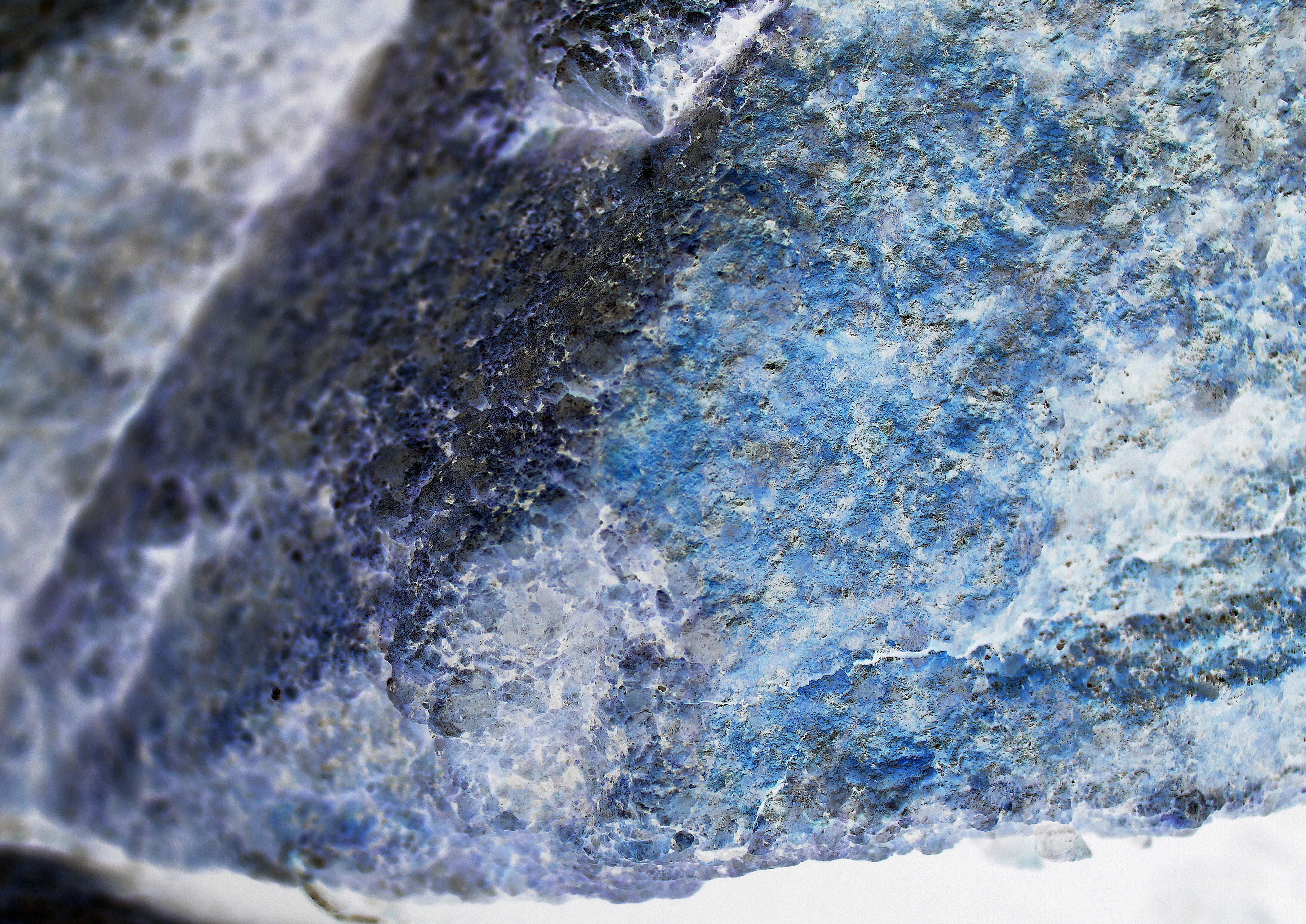

Photo Credit: Joel Clark