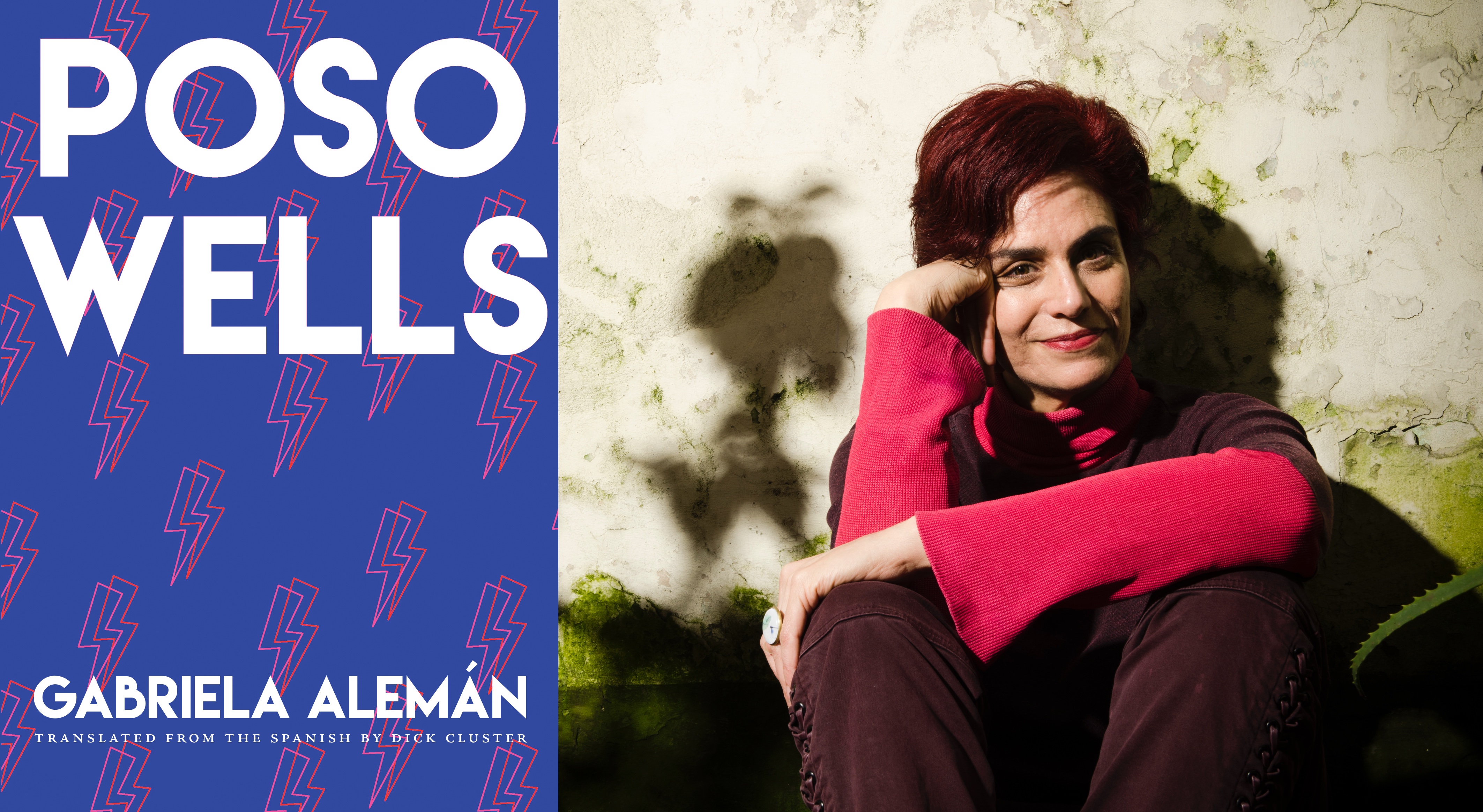

A few years ago, Gabriela Alemán attended a book fair in Calarcá, Colombia. During a walk around the city, she fell and scratched her knee. To protect the wound, Gabriela put some hand sanitizer on her injured skin. That futile action led her to spend months convalescing, fighting a bacterium that almost destroyed her leg. Her knee was replaced by a platinum piece that allowed her to walk again. Gabriela Alemán, the Ecuadorian writer who was selected in 2007 as one of the thirty-nine promising writers under thirty-nine years old writing in Spanish (Bogotá39), is currently an important example of writing from the southern region. In this interview with MFA candidate Teresita Goyeneche, Gabriela discusses how her precarious knee helped her create one of her female protagonists; her curiosity and how that feature led her to build fantastic stories without losing verisimilitude; and Poso Wells, her first translated novella into English, published by City Lights in August 2018.

Your undergraduate degree is in Translation. What do you think about being interviewed in Spanish even though the piece will be published in English?

The experience is fascinating. As translators, we have to go back into the history of words and practice a certain kind of archeology of the language to do our job. For me, it was interesting to work with Dick. He [Dick Cluster] had experience translating Cuban authors. And there was this whole chapter in which a word game takes place between Varas (the protagonist) and his best friend, a Mexican poet from Veracruz, Mexico who lives in Guayaquil. That particular segment is about the differences in our language [Spanish] within the Latin-American region. And also about how countries with a very strong cultural signature, like Mexico or Argentina, have left their stamp on other countries. We use a lot of Mexican words in Ecuador. Those words arrived to our country through films and music. When Dick got to that chapter, we talked a lot because he was trying to understand what the characters meant when using certain slang. Especially when he got to that part where I used a song of Café Tacvba, the Mexican band. He did not even try to translate the song, he left it in Spanish. So, you know? After this whole process, I think it is pretty fantastic to be interviewed in Spanish knowing that you’ll translate me later.

In Poso Wells, I sometimes felt like I was in places that looked like popular series such as Twin Peaks or The Handmaid’s Tale. Why do you think that was?

I did my PhD thesis on Ecuadorian cinema. Most of that work studied the first movies made in Ecuador around the twenties and the thirties. During that time, the world started to produce narrative movies with three acts and cliffhangers. Those were the years of [D.W.] Griffith. Right after the breakthrough of names like the Lumiére brothers, or Méliès. And there was something that seemed weird, or maybe it wasn’t. The literature of the 19th century created the youngest of the arts, which is the cinema. Everything that Griffith created came from Dickens’ serials. Dickens was paid by the word, and he needed to have many characters, stories, and sub-stories to make his pieces longer. He wrote in weekly publications. Every Friday he submitted chapters, and he had to find a way to keep his readers interested. In Poso Wells, every chapter ends with details that leave the reader hanging and needing to know what comes next. That structure is like a full loop that puts together literature and film.

You are a journalist, an editor, and a writer. You’ve worked in films and graphic novels. How is that reflected in Poso Wells?

In Ecuador, we do not have detectives. So, I had to think about how would that tradition be translated into my country. The closest character I could find was a journalist. That was how I created Varas, a poor journalist who was loyal to the truth. This strong-headed character wanted to find missing women but ended up immersed in an extraordinary investigation that involved a corrupt politician. I needed that satirical tone because of what was behind the story was the real reason I wrote it.

Currently, there are around four thousand people missing in Ecuador, and no one speaks for them. From that number, at least 70% are women and let’s agree that Ecuador is not an anomaly. Even so, this is a phenomenon we don’t talk about that often.

I gave Poso Wells the fantastic twist because ten years ago, every two or three days we read these short notes on the B side of the newspaper, announcing a new disappearance. I knew the only way for us to look at such terrible events with different eyes was through humor and fantasy. That allows the reader to see themselves without looking away. In order for me to do that, I had to use techniques from journalism. I also brought details from graphic novels to create the imagery.

I read that after publishing Poso Wells in 2007, you had a writer’s block. What happened then?

Bogota39 happened. Back then, I was writing for me and no more than 400 readers in Ecuador. That was my audience. But then, I was selected to be part of this list of young writers. I went to Colombia. There, I met and became friends with other writers who I ended up admiring like Pedro Mairal, and Claudia Hernandez.

If you ask me about Bogotá39, the first thing that comes to my mind is me going out to a bookstore at the end of the day and buying books of the other authors who were selected. The only one I already knew was Junot Diaz. I don’t know if you remember, but ten years ago books written by Latin American authors did not circulate within the region. So, I bought 38 books and during my time at Bogotá39, I read at least some pages of each and every one of the participants. Aside from the joy and fun of being part of this prestigious list, I found out there were a lot of people doing very interesting things who were also out of my radar. I spent the following years thinking “What am I going to write? There are so many books in the world. Such great pieces. If I’m going to write something, it has to make sense.” I was paralyzed for three years. And then, I realized that it was in me to talk about contemporary Ecuador and its connection with other traditions of the world. At that moment, we had a local debate in Ecuador. Most people said that in order to be read, Ecuadorian authors had to write from New York or Paris. Otherwise, the writing was too local for international taste. I thought that was nonsense. Pedro Páramo (Juan Rulfo’s novel) could be read everywhere in the world, and it talked to every reader. Pedro Páramo narrated a particular place, with a particular voice, and it was set in this particular atmosphere, which created a whole world. When I got to that realization, I started writing again. I wrote Album de familia (Family album). A collection of short stories about the recent years of Ecuador. That was my way to dialogue with my contemporaries.

Reading through your Facebook posts, I found that you were looking for a Quichuan Translator. Why would Gabriela Aleman need such thing?

I have worked on three different novels during the past four years. One of these projects is about a woman named Dayuma who died five years ago. She was one of the Huaorani women (an indigenous community) who connected Summer Institute of Linguistics missioners with her community. They got to Ecuador in the 50s.

I need to understand many things before taking on the politics and the history of this story. But first, I want context. I want to understand the difficulties of –for example—translating the Bible into a language (Hoaurani), where the concept of God or future do not exist.

Humo (Smoke), your most recent novel, portrays Paraguay with great detail. Paraguay is an unknown territory even within Latin America. How long did it take for you to do the research to write Humo?

Twelve years passed since the moment I knew I wanted to write the novel, and the day it was published. I moved to Paraguay with my family when I was seventeen. I lived there during the last years of Stroessner, the dictator. During that time, I took journalism courses. Our teacher said straight out that there were five people in the country who should never write about, talk about, or investigate. That was how things were. I learned about philosophy, history, and language. But as soon as I left, I realized that I had learned from official textbooks, which were censored in one way or another. Since I was twenty, every time I went to a different country I looked for books about Paraguay. It was not like I sat down one day and started doing research. I had spent some years finding books and creating my own idea about the country: the missionaries, the Chaco war, Stroessner. One day, every piece got into place. And I knew it was the moment to start writing.

In 2017, I read a personal essay you wrote about your cyborg knee. While I read Humo I couldn’t stop thinking that the Gabriela who limped (your protagonist) and you were the same person…

Twelve years is a long time to write and rewrite a novel. The book passed through many phases. For example, it was hard to talk about the history of a country if I didn’t know the language. Ninety-nine percent of Paraguayans speak Guaraní. Eighty percent speaks Yopará, which is a mix of Spanish and Guaraní. In Humo, I wrote about the past allowing myself to tell that story through the voice of a European migrant. The hardest part came when writing about the present. But, I thought: why wouldn’t I use myself? I lived there. Although I did not understand many things, there were many others that I knew very closely. Obviously, Gabriela—the character—is not Gabriela Alemán, the Ecuadorian writer. However, through this character, I could use elements that helped me to portray her. Like the limping. I knew the sound a walking-stick made over a wooden surface. I knew how that sound traveled across space. Those essentials helped me to create the gothic atmosphere I wanted for the house where the story took place.

What would you recommend to Latin-American writers who pursue a North American audience?

My head is divided between the point of view of the writer and the point of view of the editor. I have been editing for three years with El Fakir Ediciones. A publishing house I opened with my brother and a friend. Last year, we were invited with a bunch of publishers to Queretaro. At this meeting, we discussed a compilation of young Latin American writers that we were going to publish together. It caught my attention that publishers from Argentina and Uruguay –two countries with a lot of ideal readers—were saying that they were not printing more than five hundred copies. I thought we were doing, at least, a thousand. But, then the book came out in February and we had sold only fifty books.

I understand for a Latin American writer it is unsustainable to only target the Latin American reader. But think about how many of us were translated ten years ago. Roberto Bolaño opened a door, and through that door entered great authors like Alejandro Zambra or Valeria Luiselli. And also, the North American market realized some years ago that only 3% of the books published every year were translations. Suddenly, small publishers who specialized in translations showed up. Organizations like PEN started supporting translators.

The publishing world works at the same pace as if we were still in the 20th century. We are moving forward very slowly. But I can see that currently, there are more doors open for Latin American translations. Not only in English, but in French.

Photo courtesy of City Lights Publishers