By Lucas Lyndes

Latin American fiction in translation has essentially had two watershed moments in the United States. The first was the “Boom” of the 1960s, which familiarized readers with the names of Mario Vargas Llosa, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, and Julio Cortázar, grouped together mostly because they happened to publish some seriously great novels at about the same point in time, despite fairly drastic differences in age, prose style, and thematic concerns. The second of these moments was this past decade, with the translation into English of that one-man Boom named Roberto Bolaño.

Through their exposure, these writers helped (and continue to help) pique interest in Latin American literature in general, leaving a bit of room at the edges of the limelight for others who may not have otherwise succeeded in attracting much attention, the English-language market being what it is. And by “what it is,” I mean a notoriously hard place for translations to get published… not to mention reviewed/read/noticed (all of which may just be a self-fulfilling prophecy on the part of traditional publishing, but that’s a subject for another day). Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, given the underwhelming amount of space afforded works in translation when compared to the total number of books published each year, that there are more than a few writers who have been unjustly neglected and forgotten. Consider this my small contribution toward rectifying that situation.

The best-known “Boomers” all earned the praise they received, there’s not much arguing that; but there are a couple names that consistently come up when academics and readers set about expanding the club beyond the fantastic four, writers who may have reached their peak just before or just after that particular period in time, but who are associated with the Boom to some degree—writers like Juan Carlos Onetti, José Donoso, and Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

Of these, the one dearest to my heart is José Donoso (Chile, 1924-1996). His early novels, such as Coronation and This Sunday, are tightly-plotted and entertaining, if pretty conventional, primarily focusing on class differences and social change in Chile during the 1950s and ‘60s. Then there’s his 1970 masterpiece, The Obscene Bird of Night, which is a different beast entirely. This feverishly fragmented book tells the story of Humberto, the last in a long line of aristocrats (putting a new twist on an old concern of Donoso’s) who is born deformed, leading his father to surround his son with circus freaks and other aberrations of nature so that Humberto will grow up believing himself normal. That’s quite the springboard for a demented plot, certainly, and Donoso doesn’t shirk. This is the book that singlehandedly made me fall in love with Latin American literature when I stumbled upon a used copy at the impressionable age of twenty.

Though the Boom may have accommodated a range of birthdates, one demographic that you won’t see come up much in the discussion is women (also a subject for another day). While not part of the Boom per se, Cristina Peri Rossi (1941 – ) is a Uruguayan poet and novelist who also began publishing in the late ‘60s. She has been a new discovery for me, however, with a surprising amount of her work translated into English. The stories I had the pleasure of reading (from her collection Los Museos Abandonados, or Abandoned Museums) make use of a lyrical, carefully constructed prose style to create miniature worlds built from equal parts surrealism and social consciousness (well, maybe a tad more surrealism), along with a strong dose of recontextualized Greek myths, all with a lighter touch than you might believe possible based on such a description.

More recently, Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous success has brought with it a renewed interest in Spanish-language writers. Publishers such as New Directions have done an admirable job increasing the visibility of major contemporary authors such as César Aira, Enrique Vila-Matas, Javier Marías, and Horacio Castellanos Moya. Of course there are other publishers and many more writers doing equally fantastic work, even if they have not managed to build the same readership.

Mario Bellatin (Mexico, 1960 – ) is one of the most original authors I’ve had the fortune of reading in any language, achieving stunning effects with a deceptively skeletal style and a seemingly limitless supply of rather untraditional characters, including a blind poet cum cult leader, a hairstylist running a refuge for the terminally ill (in his beauty shop), and a paraplegic who also happens to be the world’s leading trainer of Belgian Malinois dogs. Reading Bellatin can either be an epiphany or a source of endless frustration, depending on how you like your fact and fiction mixed (beyond recognition, in this case) and how tidy you like your allegories (Bellatin seems to love a good leg-pull, purposely hinting at a deeper meaning that may or may not exist). His highest-profile translation into English is The Beauty Salon, brought out by City Lights Publishers, who really know their stuff when it comes to Latin American fiction (Guatemalan author Rodrigo Rey Rosa is also worth checking out).

Sergio Chejfec (Buenos Aires, 1956 – ) is another author who revels in confounding readers’ expectations of what a novel should be. My Two Worlds, published by the University of Rochester’s Open Letter Books, inserts us inside the head of a writer visiting a foreign city to attend a literary conference just before his 50th birthday. Basically, the reader keeps him company as he searches for a park to take a walk. The ground covered literally here is inversely proportional to that covered mentally by the narrator, whose mind is a disarmingly original place to spend a hundred and twenty pages.

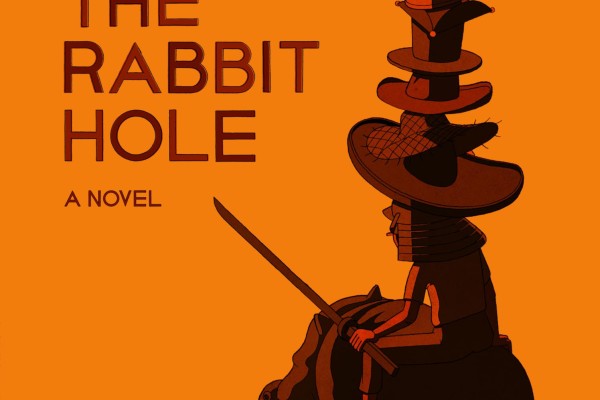

Among the newer names in Latin American fiction, Juan Pablo Villalobos (Mexico, 1973 – ) caught the attention of the Spanish-speaking literary establishment in 2010 with his debut novel, rendered into English as Down the Rabbit Hole. The translation was first brought out in the UK by And Other Stories, a young publishing house doing noteworthy work, and then picked up in the US by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Villalobos knows that the funniest subjects are also often the touchiest, making disturbing comedic gold out of the Mexican drug war as seen from the viewpoint of a cartel boss’s son, Tochtli, who is on a quest to obtain the ultimate in exotic pets: a Liberian pygmy hippopotamus. It makes me wish there were more books that could be described as simultaneously grim and whimsical.

Despite a marked trend among more recent generations of Latin American authors toward aping the latest and the greatest writers coming out of the U.S. and Great Britain, I am still consistently amazed at the breadth of styles and the staggering imaginative power to be found in Spanish-language fiction both old and new, making it one of the most literarily interesting regions of the globe, to my mind. Here’s hoping it stays that way—that those works that do make it into translation continue to receive increased attention from readers in English-speaking countries, and that more examples of great Latin American writing are translated in the first place, because there are vast territories here that the rest of the world has not yet had the pleasure of discovering.

——

Lucas Lyndes is a (commercial) translator by day and a (literary) translator by night. In 2010, he took a break from the computer to get married and co-found Ox & Pigeon Electronic Books (@OxandPigeon), a digital publisher that uses the accessibility and convenience of electronic publishing to bring the work of great authors from around the world to English-speaking readers. He lives in Lima, Peru.