I had forgotten what wet felt like. Perspiration pooling from my pink water jug on the side table next to my hospice bed—how it grew. Clanking of ice cubes in my mother’s glass settling on top of the side table—how they created waves. Pellets of rain that leaked through the window sill—how they jumped from the ledge and awaited the floor. Even their mud, my fresh blood—how they created sludge on the cloudy floor. How they knew I was thirsty.

My lips resented my fingers, how they selfishly grabbed the stream of water rushing from the faucet. I can’t understand why I rushed that time. Why I rushed being alone, away from my hospital room, from my tumor. Why I chose to forget what it felt like to be clean.

Once, I cried, and pretended it was rain. I tried to make the water flow like a river in pool of my neck, and bathe in it. I tried to drown my toes in the puddle above my larynx and shave my legs against my trachea; my lymphoma-lined lymph nodes, a pool noodle, to float on through the Rituxan river. But it was too shallow to swim in, and quickly evaporated.

I had forgotten what it felt like inside my throat. What is felt like to swallow. How my throat’s walls constricted to create a tunnel for water to flow. How do you choose not to choke? It was being asked what water tasted like. It could be sweet or tangy or spicy, bland, or uncomfortably warm, like falling in love for the first time. However, I find that it stings, like a cold that I only feel when I swallow.

The first time I felt water was from a sponge. I wasn’t allowed to drink, so my mother would offer a sponge the size of a watch’s face dipped in water. They thought it would be enough to quench my thirst. My tongue dug to release the water. I wanted to explore every hole, to rip the sponge to pieces and ravage its yellow flesh. It flooded the cracks on my tongue and burned. I didn’t remember water feeling like that.

I suckled the sponge, with the same familiarity as I had with my mother’s creamy breast, the sensation of primal thirst untapped in my memory. She would look vacantly outside as she did this. Her fingers held the sponge delicately, her other hand secured in her pocket, maybe fondling her sky-blue Bic lighter like a rosary. Perhaps she felt the same sucking, the similar sting in her breast, remembering how my teeth filtered her milk, the way my tongue pulled it out and floated in my mouth’s creamy bath. She had lost herself even before this moment. I swallowed the sponge whole; I hoped it would wash away my caked-on tumor. A wound opens. She started asking the nurses to do it instead.

“Would you like to take a shower?” asked my nurse. I couldn’t remember the last time I had taken a shower. Five days, ten days, felt recycled in the hospital. They don’t want you to remember that the world keeps moving without you inside it. She guided me to the communal hospital shower no larger than a bathroom stall, with silver hand rails and crimson emergency buttons blocking me in. Her dark blue nails clutched the blue veins that throbbed in my hand as I stepped over the ledge into the shower. Her hands covered the hole where my IV lines sprouted from my chest with a plastic wrap. I can feel the silver of her wedding ring sharp against my collarbone. It was the first time someone touched me outside of an operating table or a death bed, without a barrier between skin. “Don’t get the IV pole wet” she said, “I’ll check on you in 10.” She touched me and wasn’t afraid that I would shatter.

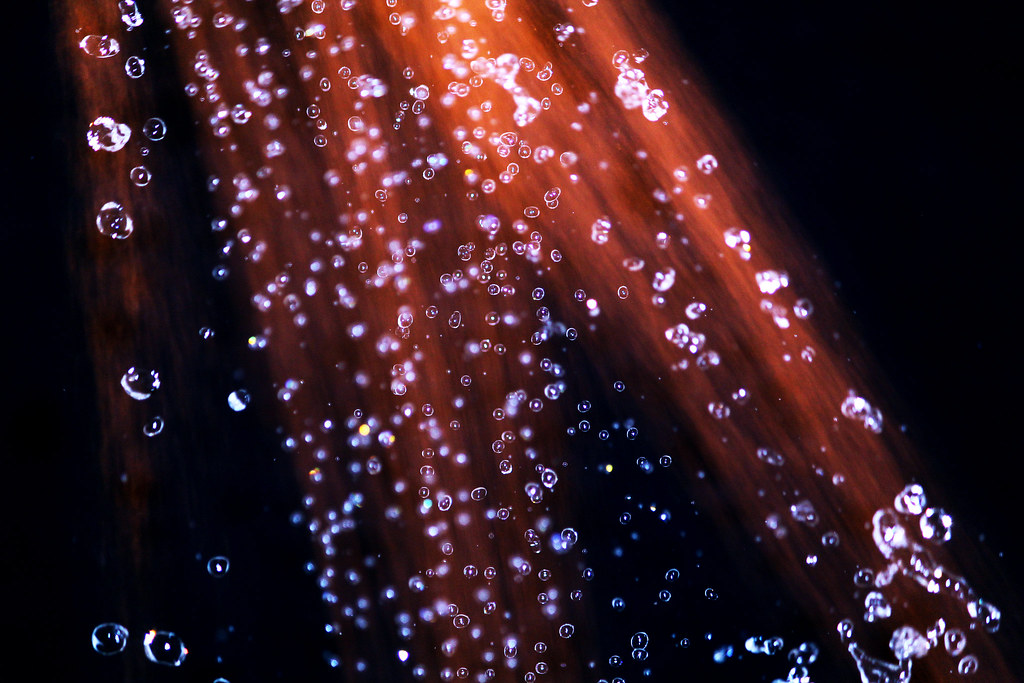

I saw my body naked for the first time. My stomach was filled and expanded like a water balloon from the fluids, yet the skin looked like it had been melted from the steam. I had been drained, the opening in my chest leaking as water was recycled back in. My right foot met the water first and grew a darker hue of fuschia. It jumped back as it was met with a greater heat than I had remembered, a sting of pain thrusting up my body. I massaged algae shampoo into my patching hair, the chemotherapy showers washing it down the drain. I held my deflated breasts in my hands and tried to remember what they felt like, if water sliding off my skin was supposed to burn.

Having sex in the shower is similar to the feeling of suspension—time discontinues, and nothing moves despite the force of two bodies acting on each other. I try to settle in this state, but my particles are too small to stay suspended; my chemicals knew all along. But things break, and I sought out that feeling of stillness, that feeling of falling that kept me stuck in the rain.

But with you, sex is like flying, and I am afraid of heights. You, like my Rituxan, reteach me how to touch. We smear our bodies with shower scum as we slip like seals against the gilded shower handle, your fingers roll my nipples into little balls of clay. Our voices are wet. You get lost inside me, and I get lost in the clouds. You move my hands to show how I find myself again.

I find small memories pressed into your body: a scar on chin from falling off your bike, the absence of a sacrificed mole, the stretch marks you call your “tiger stripes” that create crosshatches on your thighs. I remember the heat you pull from me. I wonder where you keep it, maybe inside your wallet next to the poem I wrote about childhood butterflies and hide-and-seek.

I had forgotten what remembering was like, the showers of my past opened a hole in the sky to everything I tried to ignore. It’s hard to pretend not to care about all the drops of water I missed before. I opened my mouth, let the water fill me, overflow down my neck like a waterfall, letting my tongue drown in rain.

My tumor bathed in its own terminal, and liberating shower. It drank my Rituxan, like rose-flavored milk, from the hole above my breast, our relationship growing and dying in unison. I felt a breeze from the shower. I could just step out, letting my right toe dip off the ledge, my left foot breaking apart storm clouds. I want to fly. But I can’t leave—I can’t forget this feeling, this sting, this heat, this pull, this burn this fullness, this feeling of here, this feeling of wet. Above the hole in my chest, a watermark splintered, its pink, spongy surface resembled a poem I can’t forget. “Rachel, it’s time to go back to your room.” Write this down.