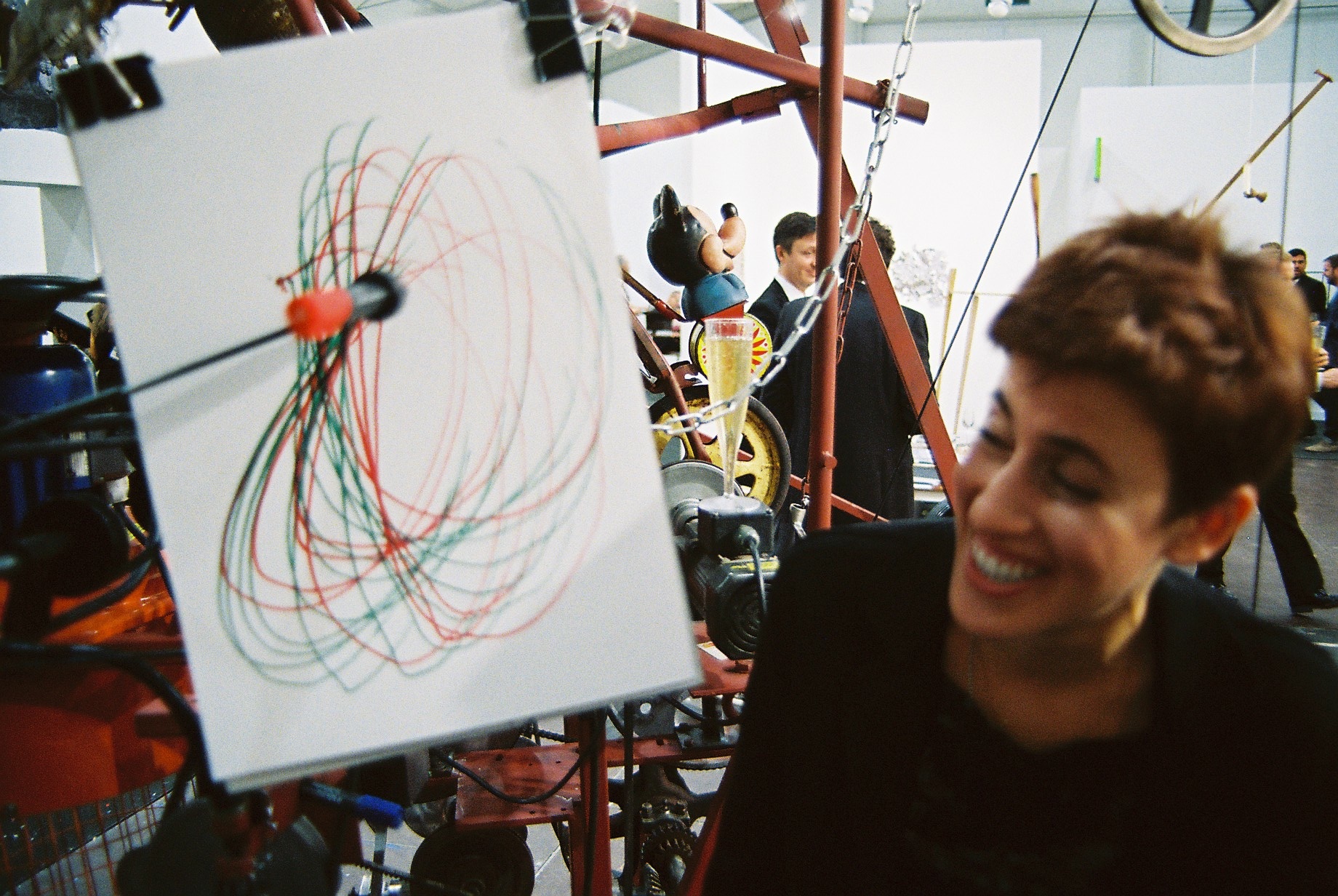

Image courtesy of Lincoln Center Film Society, “Autumn Almanac.”

by Ela Bittencourt

The complete retrospective of Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr (at the Lincoln Center Film Society from February 3-8) brought together all of his films, including the rarely seen Macbeth. The showings provided a unique opportunity to track Tarr’s artistic development.

Tarr’s work is usually classified as “socialist-realist” (his earlier films) or “modernist” (his later work). The two are presented as stark opposites. Tarr rejects this classification but it makes sense, on some level. In the socialist-realist vein, films like The Family Nest, The Outsider, and The Prefab People focus on the lives of young couples battling the harsh realities of communist Hungary. These films dissect how the shortcomings of a political system impact families, and introduce Tarr’s fatalistic vision of relationships. To quote from The Outsider: “The family life, a hearth of discord.”

Tarr began changing approach with his 1982 adaptation of Macbeth. The film introduced his interest in new themes such as power, manipulation, and female sexuality. Macbeth was shot in two continuous takes, mostly in close-ups. The resulting film did not deliver great Shakespearean performances but was remarkable for its intimacy.

In Autumn Almanac, Tarr’s cinematography moved further away from a deadpan, realist, documentary-style to a stylized Bergmanesque color palette with dramatic light effects. Confining the set to the interior of a rundown manor, Tarr staged a nuanced, claustrophobic drama of familial intrigue and boiling passions. At the center of the story is Heidi, an ailing heiress, who confines in a destitute alcoholic teacher. When Heide’s nurse seduces the teacher, she sets in motion a series of psychological manipulations and unexpected reversals.

Autumn Almanac marked Tarr’s abandonment of socialist apartment settings in favor of remote landscapes. Post Autumn Almanac, Tarr’s films universally feature ample use of outdoor space. Nature becomes its own character; the weather shown in destructive glory, with long shots of torrential downpours and gusty winds. There is a sense of timelessness. The small towns and the crumbling manors in Autumn Almanac, Werckmeister Harmonies and Sátántangó seem almost feudal.

Tarr began collaborating with Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai in his film Damnation, which perfects the theme already present in Macbeth and Autumn Almanac; masks, or social, deceitful, roles. Damnation also marked Tarr’s return to black-and-white film. The protagonist, Karrer, vies for the heart of a married cabaret singer, while engaging her husband to smuggle a mysterious package. Karrer’s monologues show him as a character of infinite complexity; his nihilism and philosophical bent borrow from Shakespeare, Beckett, and Dostoevsky.

Tarr’s masterpiece, Sátántangó, is in some ways a culmination of his artistic journey. The film builds upon Damnation by depicting farm inhabitants ruled by apathy, lechery and mistrust, who waste their time on drunken festivities. Two men presumed dead, Irimiás and Petrina, are returning home. Their promise to restore order has biblical overtones. In reality, the two men have been hired by the police as spies. With lofty speeches Irimiás, the false prophet, persuades the farmers to give up their savings, and to abandon their homes, in order to build a new utopian community.

Stunningly filmed in black-and-white, with long panning shots and an epic length (over seven hours), Sátántangó is a powerful commentary on utopian thinking—from Christianity to socialism. It also famously includes a scene in which an unloved girl-child wrestles with a cat and forces it to drink milk laced with rat poison, before committing suicide. The film explores the human capacity for evil and delusion.

Watching Tarr’s films it becomes clear that his midcareer shift towards modernism allowed him to confront the disheartening realities of communism symbolically. This shift may have been originally driven by political restrictions, however it seems to have also altered Tarr’s vision of the world and his characters. As Tarr put it in his interview with Indie Wire: “I began to understand that the problems were not only social [or] ontological … They were cosmic.” As Tarr evolves as an artist, his characters become stripped of sociopolitical realities. His evolution seems to help him explore the universal qualities residing in all of us, ultimately developing his own form of humanism—bracing and without illusions.