A man goes into a gym, thinking it’s a dance school, and waltzes with a punching bag. He enters an airport, thinking it’s a movie theater, and ends up on a flight. He stumbles into a military recruitment office, thinking it’s a high-end clothing shop, and sets off a grenade. As a kid, I watched Mr. Magoo cartoons because they were on, not because I necessarily enjoyed them. In the ’80s and ’90s, they were a daytime rerun staple on a variety of different cable channels. They filled a void, killed time, for both the station and its viewers. Mr. Magoo cartoons are built on essentially the same gag, played over and over: A nearly-blind elderly man, too proud to admit the severity of his nearsightedness, tries to go about normal life unassisted and causes mayhem. Magoo was something distinctly other, a character you never felt sorry for.

***

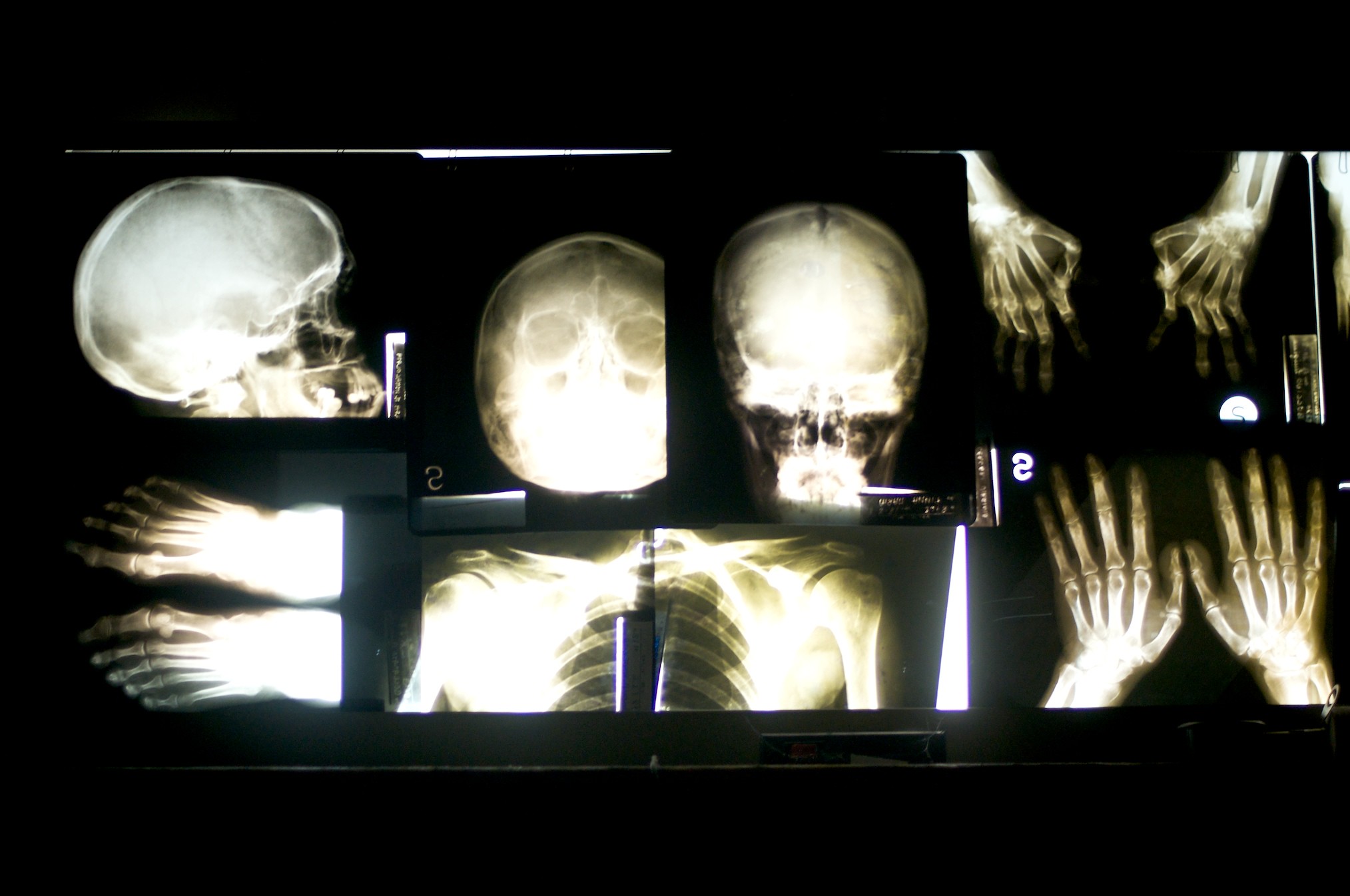

I’ve largely only had one recommendation to guide me through my decade of fighting off vision loss: avoid heavy lifting. It’s a general recommendation—there’s no weight limit or lift-duration cut-off to follow—and it’s also an unsure recommendation. Heavy lifting could cause or contribute to a retinal hemorrhage, but there’s no proof that it will. It’s just a possibility, a guess. But one I’m expected to hold to, just in case.

***

Physical labor defined most of my early life. Raised in a rural area by low-income workaholics, I learned from an early age to establish my worth by how hard I could work. I mowed my first lawn for money when I was ten years old; I can’t think of a year since when I didn’t take on at least one physical labor job for extra cash. Both my stepdad and my biological dad are landscapers. My mom comes home from hauling mail and works outside chopping wood or cutting down brush. I always imagined I would end up being a landscaper, or at least working outside in some capacity. It wasn’t what I dreamed of doing, but it seemed inevitable, a destiny I couldn’t escape. Like my eye condition, it was something determined at birth and out of my control.

***

Though it makes me feel like a bad person to admit it, I’m a bit uncomfortable around blind people. Unsure of what to do with my body or voice, I get nervous. This discomfort is somewhat silly since my cousin Joel, who passed away last year, was blind due to diabetes-related complications for over half my life. But even with him—a person I loved dearly and felt at ease talking to—I always had some questions of etiquette: Do I announce myself, or does he just know my voice? When I lean in for a hug, do I tell him? When do I describe what he’s missing, and when is it insulting? I never asked him these questions because I didn’t want to make an issue of his blindness. But now I realize the error in this logic, because what’s more caring than asking a person how they would like to be treated? When I interact with blind, or partially blind, people on the bus, or at the doctor’s office, I’m reminded how little I know about their world. I’ve always been afraid to ask, always avoided real knowledge. Out of my fear, I’ve allowed representations to fill in the gaps, settling for caricatured notions, half-knowledge of a human experience.

***

Despite the simplicity of the premise, Mr. Magoo is a surprisingly enduring character. His 1949 debut in The Ragtime Bear made him one of the first human cartoon characters—until that point, cartoon characters were almost entirely animals—and the only reason the studio gave the green-light to the project was the presence of a bear. It turned out people wanted to see human cartoons and Magoo quickly became a regular figure in ’50s theatrical shorts and the star of one of the first animated television shows in the early ’60s (The Mr. Magoo Show). The first animated Christmas special came soon after (Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol), another television show in the mid-’60s (The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo), yet another show in ’70s (What’s New, Mr. Magoo?), a live-action feature in the late ’90s (Mr. Magoo), and a long stint as an animated spokesman for an optical company in the mid-’00s. His endurance has always been somewhat baffling to me, since I’ve never met anyone who claimed to be a fan of the cartoon. Even his creators, aware of the gag’s limitations, wanted to retire the character after his first appearance.

***

My current eye doctor doesn’t talk about the future. When I try to bring it up he pulls back. The treatment is working now, why would I want to consider it not working? My old eye doctor considered everything an unknown, the treatment a bandage. He was sure I’d one day go blind, and all we could do was hold it at bay. This was in the treatment’s early years, so perhaps he feels differently now that it has a longer track record, but I still shoulder his dread. Sometimes I wonder if I’m being extreme, worrying before I need to. But then my retina will hemorrhage, and I’ll wonder if I’m not worrying enough.

***

A couple years ago, an acquaintance hired me to help him with a moving job. I worked for a moving company in my early twenties and over the years have helped dozens of friends move, so I felt confident taking the job. Though I knew it was hypothetically risky given my eye condition, I needed the money, so reminded myself that doctors are just guessing.

In large part, the job felt great. But it was more work than he had anticipated and we found ourselves under a time crunch. I’d warned him beforehand that I couldn’t lift anything too heavy, but in the rush this became impossible to hold to, and I lifted things that I knew were probably risky—large potted trees, glass tables, metal lawn sculptures—things my doctor would certainly describe as “heavy lifting.” I felt, with each item, the slight pressure behind the eyes—a pressure I never used to notice—that occurs when the body tenses to withstand a weight.

Within a week I began to notice a familiar fuzzy spot in my central field of vision. For days I cleaned my glasses, tested my vision by reading street signs or studying the small creases on a person’s face. But then the fuzzy spot grew, shapes began taking on dramatic angles, and my internal organs turned, knowing I had worked against my body.

I probably would have written off the proximity of the moving job and the hemorrhage as a coincidence if the same thing hadn’t happened when I was moving the year prior. In a hurry and not wanting to inconvenience anyone, I loaded up the truck by myself. Within a couple weeks, my world began to blur and take on a kaleidoscopic quality—a funhouse-mirror effect that I’ve come to recognize as the beginning of blindness.

***

Originally Mr. Magoo’s vision was metaphorical. Conceived by Communist party-affiliated animators, they created Magoo to represent the McCarthyist type of man who was blind to his prejudices, short-sighted in his goals, lacking vision. Blindness and vision-issue metaphors like these are embedded so deeply in the English language that we no longer notice most of them. We have blind spots, wear blinders, and the blind lead the blind as we turn a blind eye. Few of these embedded metaphors are positive—“blind luck” is about as good as it gets and even that has an implied dopey-ness. Meanwhile we applaud those who are insightful, far-sighted visionaries who have an eye for eye-opening opportunities. Even in the way we speak, the sighted are celebrated while the blind are feared, or at least made alien and undesirable.

***

Though I like being helpful, I often don’t feel comfortable being helped. Part of this discomfort developed out of the rural American gender expectations I grew up in. Though I learned to do jobs that required physical labor, I’ve never been particularly inclined toward fixing or building. I’ve worked on construction crews, cutting hundreds, even thousands of boards, but I wouldn’t feel the least bit confident building anything out of wood. Nor out of any material, really. Being a not-so-handy man growing up in a place where men were expected to be adept at fixing things and understanding the inner workings of machines, I learned early on that if you don’t ask for help few people will notice your ineptitude. As much as I’ve tried to evolve past it, I still feel the power dynamics of asking for help, the shame in admitting that I can’t do something on my own.

***

After the moving job, I finally acknowledged that I was contributing to my vision loss by being careless. So I promised to stop taking physical labor jobs, even though it felt like giving up something essential to my being—the death of a way of life. I continually have to remind myself that not giving it up could mean the death of so much more. But still I catch myself wondering about my value if I can’t chip in when needed. Who am I if I can’t physically help a friend in need, or contribute to a job that needs to get done? I’m sure by most people’s standards it sounds like a silly loss—who wouldn’t want an excuse to get out of back-breaking work?—but lifting heavy things is, almost as much as having sight, a part of my identity.

***

A few years ago my cousin Joel and I realized that we’d received the same experimental treatment. I was stunned to learn that someone I knew and loved could relate to what I go through, and we talked excitedly, comparing experiences and laughing about the horror-movie awfulness of watching a needle getting stuck into your own eye. It was the perfect opportunity to ask the bigger questions I’d always wanted to ask—the ones that might someday be important for me to know. How did he experience the world? What were the unexpected challenges, the unknown blessings? How did he transition from being an independent adult to being the youngest person in a nursing home? And how, exactly, did he become so okay with being helped? But it was a holiday, we were surrounded by family who were curious about our excitement, and I felt embarrassed. I don’t like having the spotlight on me in most situations, but especially when I’m asking another person to be vulnerable with me. So as soon as the marvel of the coincidence wore down, I changed the subject.

***

The biggest reason I don’t ask for help is that I don’t want to be a burden. I hate feeling like I’m inconveniencing anyone, and throughout my life I’ve repeatedly made myself uncomfortable to avoid doing so. On car trips as a kid I held my pee in for hours, hoping someone else would eventually need to go to the bathroom. I still find myself doing this as an adult. Rather than delay the group, I’ve skipped meals, skipped coffee, skipped changing my clothes, skipped showers, and skipped sleep. I’m trying to change this inclination to please, but the possibility that one day I’ll need constant assistance is still one of my biggest fears.

An even bigger fear is that I just won’t ask.

I don’t have a significant other or children, and all of my closest friends and family members live in other cities. No one would be required to take care of me and, given my condition, it would likely be a slow fade—a gradual decrease in one eye and then the other—rather than a sudden emergency. I imagine myself becoming Magoo, stumbling into situations, pretending everything’s fine—a clumsy joke, alone.

It’s natural to assume that if I lose a significant amount of my vision, I’ll reach out. And I hope that’s true. But I know my tendencies. Over a year ago I injured my wrist, several months later I injured my back. In that time I’ve asked for help once or twice and told friends I couldn’t help them perhaps two or three times. Both of these injuries have limited my abilities, and neither have healed because I keep doing everything myself, not mentioning that an issue even exists.

***

Though Mr. Magoo cartoons are generally not worth revisiting, Magoo reveals some very human fears about blindness. It’s perhaps telling that the live-action feature was boycotted widely by disability-rights organizations—the main gag became too obviously insensitive when taken out of the animated realm. From this boycott, it came to the surface that Magoo had always been offensive. The president of The National Federation of the Blind at the time said that, “The misunderstandings of blindness caused by the Magoo character have bedeviled the lives of thousands of blind people.” Magoo was once a common insult for the blind and nearsighted, extending to the spacey, clumsy, and accident-prone. Kids who grew up blind during the height of Magoo’s popularity often speak about the damage the character did to their self-esteem. The issues they ran into and accidents they had didn’t inspire sympathy but were viewed as comedy; their problems something to laugh at. Even today most people consider Mr. Magoo innocuous, and I wonder why gags about the blind are still so acceptable. Is it because they simply can’t see them? Or is it because the sighted consider the world of the blind—a realm without our most relied upon sense—a distinctly separate universe?

***

There are days where I walk around thinking about what I might miss most. The practical benefits of sight, like the ability to pick up on facial cues? Or moments of natural beauty, like when the moon hangs particularly low in the sky or sunlight lands on top of a body of water in a previously unknown way? I think about how it could change my life as a writer, how it might change the way I experience sexual attraction, and the way I relate to a world that’s increasingly image driven. Some of my discomfort around the blind comes from seeing an image of my future self. Someday this will be you, I think, as I speak too loudly, make pointless gestures with my hands—simultaneously fearing the image and figuring out how I might embrace it.

Works Cited

Joshua James Amberson was a finalist in Columbia Journal’s 2018 Winter Contest. He is a Portland, Oregon-based writer and creative writing instructor. His work has appeared in The Rumpus, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Electric Literature, and is forthcoming in Tin House.