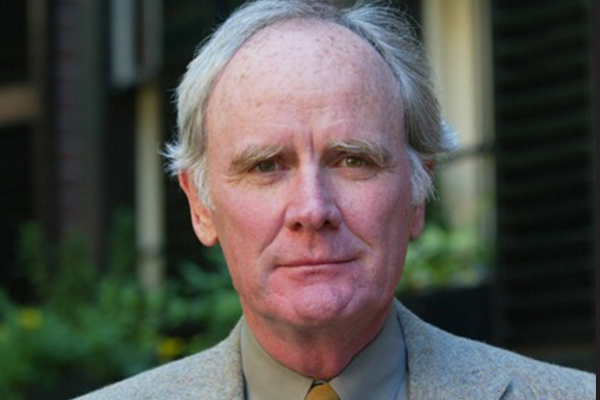

A moral compass is critical to certain kinds of literary endeavors, and no writer illustrates this better in our time than James Carroll, the author of nearly twenty books of fiction and nonfiction, most recently, the novel Warburg in Rome and an engaging work of critical scholarship, Christ Actually: Reimagining Faith in the Modern Age. His memoir, An American Requiem: God, My Father, and the War that Came Between Us, won the 1996 National Book Award in nonfiction, and in 2002 his book, Constantine’s Sword: The Church and the Jews: A History, was a New York Times bestseller. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, an Associate of the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard University, and the recipient of numerous honorary degrees. The following interview was conducted via email.

(Editor’s Note: James Carroll recently visited Columbia’s graduate writing program at the School of the Arts for a Nonfiction Dialogues event with Lis Harris.)

Christopher Merrill: You have written a number of articles for The New Yorker on Pope Francis, most recently arguing that in his stand against reactionary, anti-Muslim forces in the Catholic Church he has become the anti-Trump: “Who would have thought that, on an elemental point of liberal democracy, the United States could take instruction from the white-robed man in Rome?” What lessons should Americans draw from the witness and example of Pope Francis, especially in light of Trump’s executive order banning visitors and refugees from seven Muslim countries?

James Carroll: It is important to understand that, while the United States faces a particular crisis with Donald Trump – moral as well as Constitutional – a broad corruption of the conscience of the West is being laid bare, with other democratic nations, too, challenged by the threat of xenophobic, racist demagoguery. What is going on here? A look back is necessary.

The savage violence of the twentieth century marked the end-point collapse of the culture known as Christendom, with the Holocaust as a central epiphany: something was rotten in the West, and Anti-Semitism was at the heart of it. An amazing post-World War II reckoning began to take place, leading to a new democratic ideal for Europe as a whole, combined with a move away from violence that was reflected in the peaceful resolution of the Cold War. A chief symbol of this cultural watershed was the dramatic reform of the Roman Catholic Church, the mythic heart of Christendom. Beginning at Vatican II, the Church abandoned a theology of rejectionist exclusivism (“No Salvation Outside the Church”) in favor of an ecumenical respect for the right of others to be others (the “primacy of conscience.”) The God of damnation was replaced by the God of mercy – the religious equivalent of the politics of pluralism (civil rights, feminism, gay rights, etc.) that transformed the nations of the democratic West.

Inevitably, this transformation has sparked a massive reaction, not only because of age-old cultural prejudices, but because of built-in economic pressures and power distribution. The military-industrial complex was bound to strike back, and it has. The Cold War morphed seamlessly into the War on Terror. It is no surprise that the igniting point of renewed conflict – and military spending – should be Islam. After all, the civilization known as “Europe” came into being precisely in opposition to “the Infidels” during the Holy Wars of the Crusades. Across the centuries, Jews were the paradigmatic “enemy inside,” while Muslims were the “enemy outside.” At the end of the Cold War, with the disappearance of Soviet Communism as the “negative other” in contrast to whom Western democracies defined themselves positively, the old bi-polar structure of the imagination seized once more upon Islam as the cosmic enemy that justified ingrained habits of triumphalism and militarism.

The proximate cause of Donald Trump’s arrival may have been attached to inequality, globalism, and technology, but it was remotely prepared for by this failure of the West to fully dismantle the ua-against-them structures of imagination dating to the Holy Wars of a thousand years ago. That Pope Francis has emerged as the prophet of that dismantling shows that, in fact, the humane transformation can take place. If the once militant Catholic Church can turn back “contempt for the other,” so can the United States – even now, when the contempt is riding high.

CM: In a meditation on the life and work of the Jesuit poet and priest Daniel Berrigan, you recall that at a critical moment in your seminary education he came to embody for you “a new ideal”—a man for whom words “were sacraments of God’s real presence” and writing “an act of worship.” What are the sacred elements of writing? And how do they play out for you in your daily life?

JC: What does it mean to say, with Genesis, that humans are the “Image of God?” The word “image” is a clue. Coleridge said that the imagination is the repetition in human beings of the creative “I AM” of God. The imagination (combining thought and feeling) is the faculty of meaning. Where there is no meaning, we humans imagine it and bring it forth. How? By expressing ourselves. Expression. The chaos of experience, even if tragic, can be ordered and made beautiful by imaginative acts of expression. By, in a word, words.

The Gospel of John begins, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Logos can be translated as “meaning.” As in, “In the beginning was Meaning, and Meaning was with God, and Meaning was God.” Every time a human being discovers meaning or creates it, the divine is present. The absence of meaning – meaninglessness – is hell. Humans are defined by the unquenchable thirst for meaning, which comes about only through the “I AM” of imagination. The self-aware creature imitates the Creator whose awareness takes the form of the vast outpouring of Self we know as Being. Because the Creator is present in the very consciousness of the human, contingent acts of creativity mirror the primordial act of Creation. Such acts are both individual (the lonely artist) and communal. Words, after all, exist only as mediating symbols between persons. The word may begin as a solitary act (“I think…”), but it ends in solidarity. (“…therefore we are.”) The purpose of the word, that is, is love. Every act of truthful expression, therefore, is an opening to transcendence. (“God is love.”) Words, small w, are sacraments of the Word, big w. This idea is essential to the religions of the Word (People of the Book), and to the cultures that spring from them. The work of the writer is holy.

CM: Readers of your work know that in your exploration of religious themes you do not shy away from political issues. How do you balance righteous anger at the failures of our political system, from the Vietnam War to the invasion and occupation of Iraq and now the erratic pronouncements and policies of the Trump administration, and your desire to address questions of faith?

JC: Righteous anger is an essential virtue, especially in a nation still in the grip of white supremacy, misogyny, and the love of weapons. But righteous anger can be cruelly counter-productive in the struggle against such criminal habits of mind, and that is why it helps to reach political judgments within a religious conscience that must always be uneasy. Righteousness must not yield to self-righteousness.

As a Catholic, I have learned the hard way that there is no failure of which I can accuse my Church that I am not myself in some way guilty of. In the Biblical tradition, we believe that God comes to the people not because they are worthy, but because they are God’s whether worthy or not. Every Mass begins with repentance because we all miss the mark at times. With luck (and grace), we are all on the way to getting better, truer, more fully committed to justice and equality. None of us is there yet. Criticism of injustice, therefore, always involves self-criticism of one’s own complicity. This is the mandatory perspective of a Faith convinced that only God is God. The universal obligation to self-criticism is an instance of stark realism, but it is also plain humility…and humility can be urgently important when it comes to criticizing “the failures of our political system,” for the failures of my nation – racism, misogyny, militarism, worship of money – are in some way my failures, too. If the deepest wound in the American imagination is its habit of a self-righteous exceptionalism that sets the City on a Hill above all others, how is that corrected by critics who assume their own moral superiority?

CM: In an age of literary specialization, you have distinguished yourself from other writers by working in a variety of genres, publishing poems, plays, novels, memoirs, and books of history. Can you talk about the decision-making process that leads you to write in one form versus another?

JC: My writing apprenticeship was largely given over to poetry and plays. I learned invaluable lessons about economy of expression and dramatic structure in those years, but I did not pursue either form. I have written historical novels, but always with the aim to do more than entertain. And I have written works of history in which carefully researched inquiry sometimes opens into autobiography because I believe that the great moral currents (anti-Semitism, belligerence, racism) run not just through culture, but through conscience. And the exploration of conscience must always be personal. If I include my own story in history, that is not because my story is unique, but because, however particular, my story is typical. Anti-Semitism infects the West, but it infects me, too. So, also, with the dream of American exceptionalism that has turned out to be such a nightmare for war-ravaged people, beginning with kidnapped Africans hundreds of years ago and continuing to harried refugees today. My work as a writer – historian and novelist both – has been to identify, discover, create, and articulate dark stories that nevertheless aim to show, in Auden’s phrase, an affirming flame. I choose one form over another by instinct, and, in way, by turn. As I work, the forms of history and fiction inform each other. Having fictionalized the American failure in Vietnam (Memorial Bridge, Prince of Peace), I wrote it as non-fiction (American Requiem). Having laid out the history of the Cold War (House of War), I wrote a novel to lift up one imagined family’s experience of it (Secret Father). Having confronted the broad history of Catholic co-responsibility for the Holocaust (Constantine’s Sword), I wrote a distilled fictional indictment that made the failure personal (Warburg in Rome). My ongoing personal search for meaning and for faith has kept the life and death of religion at the center of my work, which in my case has meant preoccupation with the figure of Jesus Christ, and the community that, often despite itself, can never quite forget him.

CM: Can you describe the inspiration for your latest novel, Warburg in Rome—which is, among other things, a wonderful read? Arriving on the heels of a book-length search for Jesus in a secular age, this spy thriller might at first glance seem to be a departure—and yet there are constants, notably your determination to address the anti-Semitic history of the Church.

JC: In Constantine’s Sword, I showed that the so-called “silence” of Pope Pius XII (his failure to openly and forthrightly defend the Jewish people from the Nazi genocide) was not the crime but the evidence – the evidence of a deep theological and cultural malevolence so disguising itself as holy doctrine that the Church seemed bound to deny it. Hence the Vatican’s on-going defense of Pius XII, who may yet be made a saint of the Catholic Church.

Warburg in Rome is the story of the single most dramatic act of Catholic complicity with the Nazis, the so-called Vatican ratline that enabled hundreds of Nazi war criminals to escape through Rome at the end of World War II. David Warburg is an American lawyer, a Jew, who runs the War Refugee Board in Rome, a late-in-coming U.S. attempt to rescue Jews. His partner in the effort is Monsignor Kevin Deane, whose own ambitions for the Church – and for himself – are thwarted by what he learns with Warburg. Yes, the Nazi crime was unique, but the Catholic Church and the U.S. government are also twinned in its corruption. My purpose in writing this novel was to render the horrific abstraction of a world-historic crime in the most particular way possible, as if to learn how two characters in the thick of a moral abyss might climb out of it.

Their problem, of course, belongs to all of us. Though Warburg and Deane were compromised by institutional burdens, their own personal reckoning with the evils unfolding before them was unavoidable. The vast sweep of history, in this fiction, becomes the single blade that cuts through a handful of human lives. Their story is itself the moral rescue.

CM: Critics have invoked the novels of Graham Greene in reviews of Warburg in Rome, which leads me to ask where you see yourself in the tradition of Catholic writers?

JC: As I came of age, the so-called Catholic subculture was in its flower, and we prided ourselves on the achievements of writers who could be defined as “Catholic” mainly by being contrasted with a broader culture from which Catholics felt excluded. (Wasn’t it Orwell who said that no Catholic could be a good novelist…or, if he was, he was a bad Catholic?) That was the golden age of “Catholic writers” (Greene, but also Waugh, O’Connor, Percy, Chesterton, Bernanos, Hopkins, et al). But the category lost its salience with the disappearance of that Catholic subculture, a transition marked religiously by Vatican II and socially by the arrival of the Kennedys. My mentors were the poet Allen Tate and the playwright William Gibson. Both, as it happened, were Catholics – but in each case Catholicism was firmly beside the point of their writing. (As was true of Hemingway, O’Neill, and Fitzgerald)

Even though (or perhaps because) the Catholic sub-culture is long gone, Catholicism is key to my identity, and its themes have given me many of my subjects. Still, I have never thought of myself as a Catholic writer – any more than I think of myself as an American writer. I am a writer – that’s all.

CM: One hallmark of the Trump administration has been its serial lying. How should writers respond to this systematic assault on the truth and the so-called “dishonest press”? What are writers to do in a post-factual world?

JC: Distinctions matter, and here the relevant distinction is between fiction and non-fiction. The discipline of fact-checking must be firmly observed – even protected – in the writing of non-fiction (Journalism surely, but also history and memoir). Facticity must be protected, even while it can be acknowledged that all perception (all deployment of facts, too) is from a point of view. The “objective truth” is always situated in subjectivity, but that makes the testing of real-world assertion by “checking” all the more important.

Fiction is another matter. Its truth may or may not be situated in time and place, but its power as truth depends on clarity of context. Philip Roth’s Lindberg (The Plot Against America) is not history’s Lindberg, but the novel’s illumination of Lindberg’s actual, if subliminal, meaning for America depends on respect for that distinction. Roth, crucially, called his work a novel.

No matter what confused Americans (or deconstructed professors) think, there is no such thing as a post-factual world. Writers must insist on that.

CM: What are you working on now?

JC: I am just completing a novel called The Cloister. The title nods to The Cloisters in New York, the Metropolitan Museum’s monastery-like center of medieval art, which is, in part, the novel’s setting. One of the characters, a survivor of Drancy, the French concentration camp, is a docent at that museum. She encounters there a Catholic priest from a nearby parish who is driven to the faux monastery by the unexpected, and deeply unsettling reappearance of a long lost friend. To his surprise, the French woman offers him a way forward, even as – equally unexpected – he does a version of the same thing for her.

The story of the docent and the priest unfolds in relationship to another story centered in a cloister – the mythic love story of Abelard and Heloise. But The Cloister’s concern is less with the high Gothic romance than with the way that the famous monk and nun bravely engaged politics and theology, standing alone together at the great fork in the road of history, when the Church and the culture that came of it took the turn that led, ultimately, to the Holocaust.

The Cloister will be published next year by Nan A Talese / Doubleday.

Christopher MERRILL has published six collections of poetry, including Watch Fire, for which he received the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets; many works of translation and edited volumes, among them, The Forgotten Language: Contemporary Poets and Nature and From the Faraway Nearby: Georgia O’Keeffe as Icon; and five books of nonfiction, The Grass of Another Country: A Journey Through the World of Soccer, The Old Bridge: The Third Balkan War and the Age of the Refugee, Only the Nails Remain: Scenes from the Balkan Wars, Things of the Hidden God: Journey to the Holy Mountain, and The Tree of the Doves: Ceremony, Expedition, War. His work has been translated into nearly forty languages, his honors include a knighthood in arts and letters from the French government, and his journalism appears in many publications. As director of the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program, he has undertaken cultural diplomacy missions to more than fifty countries.