“Can I see, Mama?” Gretchen tugged on her mother’s mini dress.

“In a minute,” she answered sharply, struggling with a piece of poster board. “I’m tryin’ to make the pinhole the right size.”

In the living room Charlie fidgeted in his playpen, blonde curls pasted to his forehead on an unexpectedly sultry March day in Savannah. No matter that a breeze had caused Mama to open the carriage house windows and door to the courtyard: Charlie’s pink skin sweated all the time.

“I wanna see, too,” said June. Muscling between her mother and sister with surprisingly strong legs for a four-year-old, she jostled Mama so hard the poster board ripped in two.

“Girls, quit it!” Mama dropped the ice pick into the kitchen sink, reached for her pocketbook, and took out a pack of Virginia Slims. Her fingers were nearly as long and white as the cigarette she lit and placed between frosted lips.

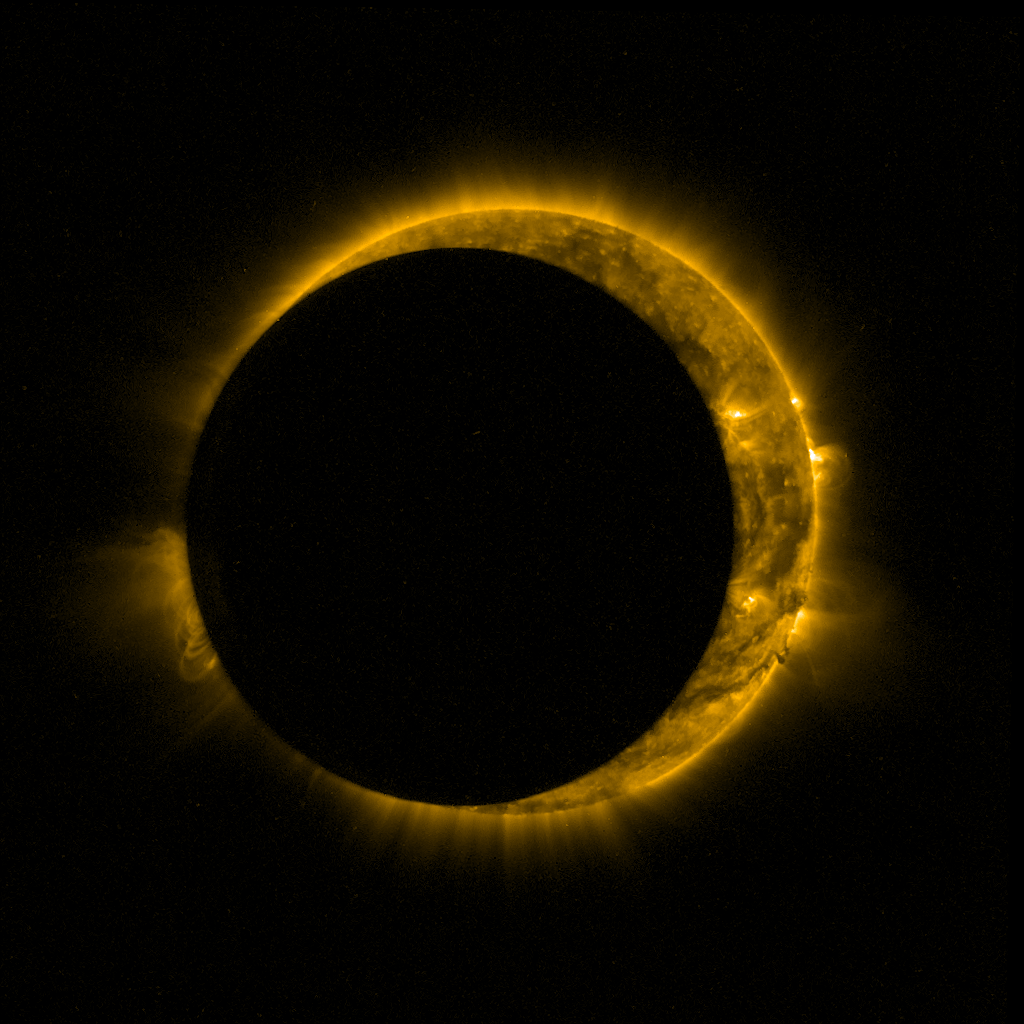

Gretchen had studied the eclipse for weeks in filmstrips and mimeographs, the sun a lion’s face disappearing behind a moon mask, leaving only a fringe of golden mane. The day before the eclipse, June had brought home a pre-school book with pastel drawings of a sun slipping behind an impish moon, casting eerie shadows on the grass. How odd, Gretchen thought, that the sun could hide behind something smaller than itself.

Charlie threw a toy out of the playpen, and Mama waved a slender arm at Gretchen. “Could you entertain him for a minute?”

She brought the plastic ring back to her brother, and Charlie gave her a mischievous look, then threw another onto the floor.

“You little rascal,” she said. Daddy’s word. Mama flinched. Gretchen crawled into the playpen and began slipping colorful plastic rings onto their teetering pole. “See, Charlie Bear, the big one goes on the bottom, the littler ones on top.” He watched enrapt as she stacked them in decreasing order of size. Just as she was placing the last, he lifted the rings from the bottom and flung them across the living room floor. They broke out in giggles.

“But Mama, is the hole big enough?” June pointed as Mama lifted the poster board to the overhead light. “Will the sun fit in there?”

“Yes, darlin’. We won’t look right at the sun—that’s dangerous. The eclipse will shine through this hole and cast a shadow on the other paper, so we can watch as it happens.”

“But why can’t we see the clips with our eyes?”

“E-clipse,” Gretchen corrected. June glared at her through the doorway. “You’re so stupid, June. You don’t even know how to pronounce it.”

“That’s not nice, Gretchen.”

“Oh, shut up, you crybaby.”

June screamed, “Mama!”

“For god’s sake, Gretchen! You’re supposed to be the mature one. Go to your room until I call you.”

“But Mama!”

“Now.” She lit another cigarette and took June in her arms.

Gretchen stomped up the stairs. Curled up on her bed, she stared out the window and watched an osprey wheeling in the Savannah sky. Before he left them for New York, Daddy had showed her the way their wings made the letter M. How their light gray heads mimicked those of bald eagles, only smaller and with striped brown tails. “Whenever you see an osprey,” he had said, “it means good things are coming.”

But Gretchen didn’t feel terribly good, and the green curtains in the girls’ room had given the daylight an eerie glow. Maybe the eclipse was a bad sign. Even worse than seeing Daddy’s suitcases in the hall.

She heard Mama move her chair below, and she wanted so badly to run downstairs, to join her and June and Charlie, to help prepare for the eclipse. But she was a big girl. In first grade now, too old to disobey orders. Daddy had given her A. A. Milne’s Now We Are Six as a birthday present in January, but she still preferred When We Were Very Young. She pulled it off the nightstand and it fell open to a drawing of soldiers in red jackets. “Wouldn’t it be fun to see those tall black hats and to look for the king?” Daddy had asked. Though he explained that now it was a queen, but God take care of her, all the same.

The flip clock on the nightstand said 9:45 am; the eclipse would start at 10:04. Gretchen read more about things that were familiar in some ways yet strange in others. A house that wasn’t like a house at all because, it seemed, it didn’t have a garden. A waterproof mackintosh (what was that, anyway?). A dormouse named, improbably, Jim.

When would Mama come get her? She heard her talking to June, laughing about something. She heard Charlie cooing and throwing things. Mama walking in her high heels to the playpen. Charlie shrieking the way he liked to, just for the heck of it. She read for a while more. Then she tried making her own name into a poem:

Gretchen Gretchen

Said to her Mother,

“Mother,” she said, said she:

“You must never go out to watch the sun

without consulting me.”

Suddenly Mama was in the room, pulling a lock of hair out of Gretchen’s face.

She pulled away from her mother’s hand. “Did I miss it?”

“Of course not, darlin’! I wouldn’t let that happen.” As Gretchen started to get up, Mama took her hand and patted the bed. “I need you to understand something.”

She wanted to listen to her mother, but the clock flipped to 9:58; the sky began to darken. The osprey flew by again, leaning on the wind, as Christopher Robin might say, and Mama pulled her chin towards her.

“Gretchen, listen. Please. You’re getting older now. You’re such a smart, smart girl—the smartest I’ve ever known. And you’re old enough to see that I…I can’t be your mother anymore. Not like I used to.”

You’re old enough to see

That I can’t be your mother

No, I can’t be your mother

Anymore

“I have three of you now, three little ones. Well, two. You’re my big girl. And now that Daddy’s gone you have to be the responsible one. I need that from you. Can you do that?”

10:00 am. A gust of wind floated the curtains for a moment, as if someone had lifted them to reveal something underneath. But it was only the toy box, a puppet hanging off one edge, a stuffed animal off another.

“Can you do that, Gretchen? Mama needs to focus on your sister and your brother, ’cause they’re too little to take care of themselves. But you…you’re strong. You can help Mama, can’t you?”

Gretchen looked down at her Buster Brown shoes.

I can’t be your mother

No, I can’t be your mother

Anymore

“Okay?” Mama asked. “All right?”

She let Mama hug her, inhaling her scent of cigarettes and perfume and the buttery scrambled eggs she had made them for breakfast.

“Now let’s go downstairs. We don’t want to miss this, do we?”

Gretchen watched as her mother’s tall, slim body left the room. Her feet felt heavy and awkward, as if the Buster Browns had filled with sand.

In the courtyard, June jumped up and down yelling, “The clips is coming, Mama, the clips is coming. I can see it!”

“Don’t look at the sun, darlin’!” Mama had brought Charlie’s playpen into the courtyard and set it under the banana tree. Next to it she’d laid an old tablecloth, and she sat on it in her pretty blue mini dress, hair pulled back in a chignon. She looked at her watch.

“10:02! Let’s get ready.”

June sat cross-legged next to Mama, and Gretchen stood over them as they positioned the poster board with the pinhole over the blank one.

“10:03!”

As the sky darkened, June fidgeted and kept leaning over the paper, obscuring the light.

“June,” Mama said, “lean back so everyone can see.”

And as the sun was slowly overtaken, Gretchen found that she couldn’t watch the paper anymore but instead stood transfixed as a crescent moon-shaped shadow passed over her mother’s cheek.