It is perhaps a few days—three, to be exact—after her brother had called. They’d found her mother’s body. She’d been dead since Sunday.

“No!” she’d yelled. It really made no sense. No sense at all, she’d seen her mother days ago; she’d watched her mother’s disapproval of those expensive Parmesan crisps she’d bought melt into pleasure as they munched them with their coffee. Her mother was really a different woman.

And that’s the one she’d lost. The mother of gentle hands and now a compassionate heart, who saw fault only to forgive it. Not the mother who had shaped her destiny, guiding her life’s journey with the chill of her disapproval.

Her mother was beautiful even at the end, an ancient child with soaring cheekbones and startling blue eyes. Always beautiful, but her daughter was not. She’d understood it at six when a street artist was employed to do a portrait of her. It did look like her, or at least summoned her essence. She’d run to her mother breathless. Her mother considered it.

“You’ll never be pretty, but you can have character.”

***

The dermatologist’s office is way too convenient, tucked away discreetly two blocks from her house. It is demarcated by a sign, a line drawing of a lotus, to identify itself as the Zen side of vanity. But that doesn’t fool her, she knows, and she’s in a panic to get filler before—before the funeral. That will smooth everything out and extinguish the anguish, she feels sharp as a sixteen-year-old’s heartbreak. She must get it done.

“Give me any cancellation,” she’d said to the receptionist when she called. “Anytime. I’m really close by.”

And now here she is. She admires the furniture in the waiting room, modern and bland, neither expensive nor cheap with its nubby fabric and pale wooden legs. The girl at the desk greets her with a smile that hints at the personal. She is a valued client, albeit a new one. She is valued!

There’s no waiting, she is whisked down the hall and ushered into a small room with a large window. The window has frosted panes, almost opaque, that filter the light. It’s either discretion or a bad view; still, it is pleasant. She sits in the patient’s seat with the ubiquitous white paper that crackles softly as shifts her weight. Shutting her eyes, she breathes in deeply. The air moves into the passages of her lungs. She imagines it spreading down through the branching passages, the bronchioles, and then to the alveoli, those tiny tethered balloons. Oxygen flowing into them, puffing them up, keeping her alive.

“I’m Rory. Would you like a water?” the technician asks. She nods, opening her eyes. He hands her a soft sponge ball and smiles at her—is it pity? There is something peculiar about his solicitude. She inspects him now as he sets up the little tray that sprouts off the chair. No, it’s practiced and professional. The technician dots numbing cream on her forehead. He is humming “Over The Rainbow.” It’s Chelsea, so it’s okay. The hum is almost like a purr, and she is grateful. He wears jeans under the male nurse outfit that wraps and ties at the waist.

“Those are lovely shoes,” she compliments him. They are blue with pointy toes and pretty remarkable.

“Thank you.” He smiles. “I think so too.” He leaves her to wait. The water is cold, she curls her fingers around it, a tiny anchor.

There is a soft knock and the glass door slides open. It is the doctor. He is flanked by two technicians, her blue-shoed friend and a young woman with streaked blonde hair swept behind her ears. The doctor smiles at her, composed.

“I am Dr. Rosenblatt.” He shakes her hand.

“You look so young, do you have a license?”

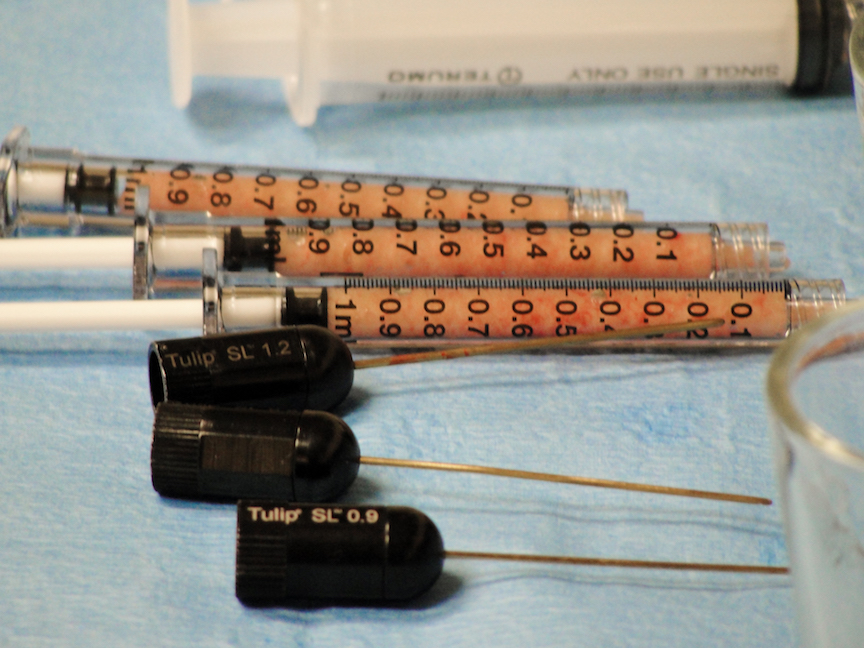

“Yes.” Now he laughs, a belly laugh that seems inappropriate, and then he pats his small, rounded stomach and smiles at Rory, who laughs back shallowly, turning his back and readying a tray. She peeks as Rosenblatt turns to Rory and sees a whole lot of swabs and needles arrayed. Everything looks mostly okay. Normal, really, as far as she knows.

“So, what are we doing?” Rosenblatt looks at her appraisingly.

“Between my eyes.” That’s where the lines are deepest, those crevices of time and worry.

“Botox, and maybe a little filler,” he says.

He is shining a light on her face, illuminating its imperfections. He doesn’t touch her.

“Whatever it takes,” she says. “I’m going to my mother’s funeral.” She wants to explain that it is not a social occasion, she is not walking anyone down the aisle, it is not an occasion of state; she will lean over her mother as she is lowered into the ground, so she will see this last act of fealty and obedience.

“I’m sorry.” The doctor composes his face sympathetically and she shakes her head.

“It was one of her last suggestions. I have to do it.” Really, in fairness, it was solicited. She had asked her mother to assess her face, and after closely regarding it, her mother had said, oracular:

“Just the lines between your eyes, smooth those out.”

But that wasn’t really her mother’s last advice. As she’d checked in at the airport kiosk she’d discovered her credit card was missing, her favorite, the one that gathered miles. Of course, it often went missing, chucked into the interstitial spaces of her bag that opened to engulf it or hiding in an obscure compartment of her wallet. Habit eluded her, keys and wallet and phone and credit cards, all the essentials often straying. She’d called from the airport to ask if she’d left it on the night table and waited, as her mother walked slowly on her pronated ankles, her feet always painful, to the guest room.

“Not there,” she’d reported gently. “Perhaps the restaurant, I can drive over.” It was a Peruvian restaurant. They’d ordered soup and rice and chicken, which came mounded on a chipped plate. They split everything. She thought about her mother getting into the car with its rusted, crumpled nose that she’d vowed to get repaired. The car that she’s insisted on driving as if she were the more competent one, hitting a pole while arguing with her own daughter. She imagined her mother closing the door to her apartment behind her, walking past the plastic daisies bunched by her front door, pushing herself forward, bent just a little, stepping cautiously but with an energy that still moved her forward, unlocking the car, sitting on the cushion compressed by her weight that hoisted her high enough to see over the dashboard, fishing her keys out of her tiny flowered sack, pulling out cautiously and driving slowly. Her mother, who still drove at ninety-one with skill, though avoiding the highways. She thought of her mother getting out of the car at the restaurant, her humped toes crammed into her shoes, the sharp orthotics that did little, the ankles distorted by bulging, purpled varicose veins, the bandaged feet rolling over the tops of her white sneakers, her mother circumventing the cement block that required a step up, walking the long way around in the parking lot, and pushing open the heavy restaurant door.

“No,” she’d said. “I’ll order another one.”

“Mindfulness,” her mother said so gently it was like a kiss on her forehead, a blessing. And that was the last word she’d ever hear from her.

“Just a little,” she says to the doctor. “I want to look like myself.”