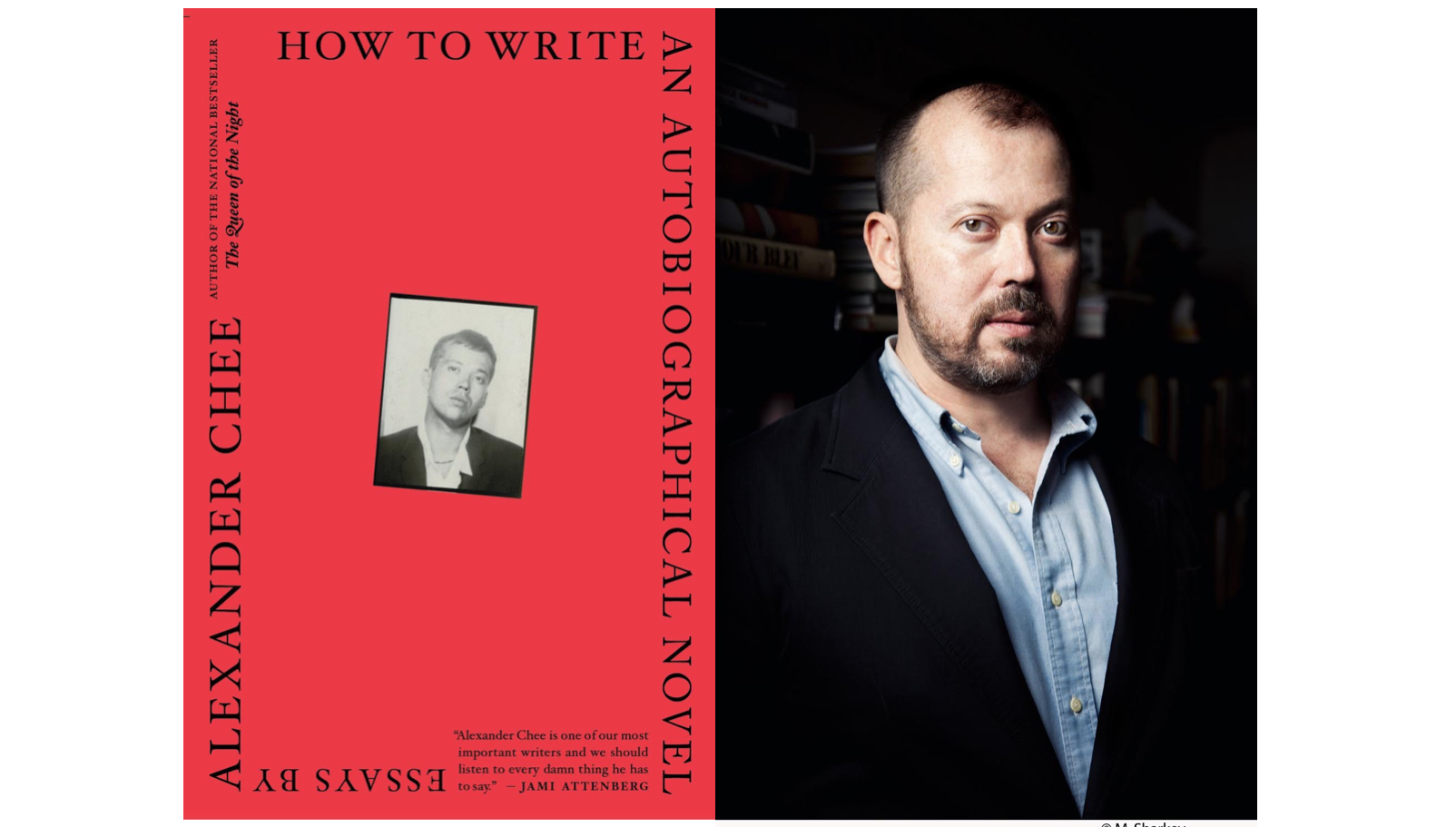

In this interview with MFA nonfiction candidate Katie Shepherd, Alexander Chee talks about learning about yourself as a writer, how we talk about trauma in MFA programs, and choosing to go back in with each book. He is the author of two novels, Edinburgh (winner of the Whiting Award) and The Queen of the Night, as well as a new essay collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel.

[Alexander Chee is the nonfiction judge for Columbia Journal‘s 2018 Winter Contest. Submit your work here by December 15.]

First of all, I think this book should be required reading for all MFA students. I just finished my first year at Columbia and, to me, when I read this collection it was all about beginnings but also about realizations, some of them hard, and I feel like it would be a warm blanket to everyone in an MFA for writing.

Well, thank you. I appreciate that.

What are you reading right now that you love?

I just finished this graphic novel Sabrina that made it to the longlist for the Booker. It’s a terrifying look at the way right wing conspiracy theorists operate. The way they sort of seize on any kind of crime that fits their idea of what’s wrong with the world and they kind of push towards this sort of mania, engulfing mania, about the kind of sexual behavior. At the center of it are these characters who are interesting. A guy whose girlfriend had been murdered very publicly— it was videotaped by the murderer— and a friend of his who’s not even like his best friend… trying to deal with his own crumbling marriage. It’s a wonderfully simple story and it was interesting to me also because I was thinking about how so much happens in it through visual storytelling and without very much conversation. It’s guided by this powerful context that the drawing supplies or the story supplies.

And in the teaching that I’m doing now, it seems like one of the things that is really difficult for students is, at this point, is creating and providing that kind of powerful context so that we get what we sometimes call Flaubert’s Invisible Plan, which is one of those things that you hear in a creative writing learning context and you’re like, Oh yes, Flaubert’s Invisible Plan. And then you’re like, how do I make that? So I’m trying to think about that. I’m thinking about it all in relationship to— my agent has put it in my head to try to create like a more specifically pedagogical book.

And I have some essays that are in line with that already, like an essay on the present tense over at LitHub or, you know, a lecture that I’m writing now about James Baldwin and Go Tell It On the Mountain and point of view and point of telling… It’s a style of a creative writing prompt that I created back when I started teaching creative writing. It was based on an approach that I learned when teaching rhetoric at Iowa when I was a grad student. So it’s sort of…

Tangible?

Yeah, but it also takes you through a process and a series of steps. So the way that I teach my students in my beginning classes is I give them nine exercises toward building a story over a series of weeks. And at each point they’re doing just one small task. Then they turn and they do the next small task. They don’t know the next task until they get there and it’s part of the power of it. It’s about learning to focus on each small piece of it, actually putting the story together, and drafting it and characters and situations and so on. But it’s also about giving them access to a process.

In a very different way, I was taught this way by Phyllis Rose at Wesleyan. Where her introductory fiction class, one week was setting, one week was dialogue. She treated it more in terms of the technical components to a story. That was a very useful approach. I tried that approach for a little while in my first two years teaching and then I thought, well, I feel like this is not quite showing us how to connect all of it. Because dialogue without character is not really anything at all.

So much this book is about all the void coming back at the writer. You write so well about the pressures of money and also a lot of rejection, but you do it in a way that, at least from the reader’s standpoint, is done very coolly. Is that something that you think is important to a writer? This idea of constantly being willing to face the unknown or the next turn?

Well, I mean a lot of it is about learning about yourself, learning what kind of writer you are, learning what works and what doesn’t. Are you a midnight writer? Are you a 5:00 AM writer? Or are you an 11:00 AM writer? Are you a 1:00 pm writer? Et cetera. Everybody has their corner of the clock. They just have to find it.

Some people, like Jesse Ball, I was hanging out with him recently and he’s describing a process where he feels a great deal about it, and then proceeds like that for a very short period of time, but most of the year is not spent laboring on it, which is sort of radical to me, because I feel like I’m running around with half-finished parts of five books right now. I already know what the next collection of essays is. I have three novels, a book of interconnected short stories and there’s a memoir slash biography about my myself and my family in Korea. And then this pedagogical book is a sixth idea.

What’s your corner of the clock?

(Laughter) All of them. Too many corners of the clock. I’ve been joking lately, but I have to make more time for my life, where I’m just forcing myself to clean up after myself, shop for food and do laundry, talk to my friends, talk to my husband, be a person. It’s very easy for me to get drawn away to the work. I think, generally, it takes me a couple hours to wake up in the morning. I’m naturally someone who starts writing around 11, in an ideal schedule, but if I can do it, it’s better to get up at 5. Getting up at that time is one best things in the world because you’re sneaking around in the dark still. It is completely different from writing at 7 a.m., which feels terrible. Like 5 a.m. feels great. 7 a.m. feels like garbage.

As a writer, I think especially when you’re in an MFA, especially when you’re in a very intense MFA and you’re surrounded by greats, like living greats, you feel like you’re trying to reach up, whereas I’ve found like the beauty of an MFA is actually reaching across, finding peers to meet you where you are.

The cohort you develop in grad school is a really powerful thing that nobody told me to expect but it’s something that I tell my students to look for now. For me, that was Chris Adrian, Ben Anastas, Emily Barton, and Anna Keesey. Those were writers that I met there who definitely had a big impact on me. Also writers who you meet and stay friends with there who don’t become household names, maybe stop writing, but still stay in your life as someone that you maybe ask to read things. Yeah, those people matter a lot. There’s a way of thinking that you share for having shared a particular education at a particular time and so there’s a shorthand you developed when you talk to each other that you’re probably not even aware of, but it’s almost like you can think faster when you’re talking to them because you have the same reference points. That’s a very peculiar intellectual aspect of it that is significant.

I have a practical question about giving time to ideas in a piece. To me one of the most beautiful pieces in this collection is the one about the roses, and when I read it, I recognize the value of having something besides writing that is an extension of yourself as a creative being in the world, but then also literally having time as far as pacing. How do you make these choices? There were so many moments in the piece where you could have gone 100 pages into that one moment, but instead it felt like it was there as some type of scaffolding.

Right. That essay in particular, for example, came out of the actual journal that I was keeping that summer then kept as a garden journal for a period of years. It’s the same journal where I found the entry about, later on in Autobiographical Novel, the entry about these stories that lead to paralysis, that comment, that’s from that same journal. I think it’s partly that you’re trying to describe something and you’re also trying to evoke at the same time, through all these details and the scenes that you create for the reader.

I had a very funny question from my student a couple of months ago, a student of mine who was like, “Mr. Chee, I used to be able to just speed through books, but I actually had to slow down with yours. How did you do that to me?” And I was like, well the essay is about what’s being evoked as well as described. You can’t rush through it because you’ll literally miss something in the process. It forces its own speed on you as a reader. That sort of blew his mind, which was kind of funny to watch. You know, so Annie Dillard used to teach us to refer to at least three to five senses on each page, and that’s what that’s for, to kind of bring the reader into the sensual aspect of the experience, the sensory aspect so that they are experiencing it in a different way inside of their mind.

You write openly about your experiences living with PTSD, and I appreciate and respect that, but I also wondered too, especially as more and more dialogue opens up around trauma and discourse around trauma, especially in our MFA programs and how we deal with that, does it require something maybe different, or maybe it doesn’t because it’s literature?

Yeah, I think it’s the intersection of several things unfortunately that we’re facing right now. I’ve had so many people reading this book tell me that they had finally been introduced to things that they had suppressed for a long time or they have been able to go to a therapist and talk about things that they’ve never been able to talk to about. It’s been a very moving part of having published a book is having people tell me what they have experienced.

One of the things that it highlights for me also is like the profound health crisis that we are all having together in this country. Where we’re not having regular access to healthcare, much less mental healthcare, there are these ways in which there’s so much unprocessed trauma in the landscape for people and so they end up trying to write about it as therapy, but a writing class is not actually a therapeutic space, so then you run this risk of re-traumatizing yourself when you’re having it talked about in workshop by people maybe who have no reason to suspect that you are writing about something personal and you don’t feel comfortable warning them that you are, maybe.

Certainly the first time I ever workshopped a story about my own abuse I did not tell the class that it had an autobiographical basis and I feel like, maybe I’m wrong, but certain classes would really struggle with that knowledge in a fiction workshop. So maybe we have to address things at several different points. Right?

I was talking with someone just the other week at a conference I was at. This person had a student who is trying to write about trauma. This person was asking me for advice, because they had no experience how to talk to this person about it in their work on the outside chance that it was real, and I was like, wow, I have been dealing with that in class a lot. And I don’t know if it’s students who feel comfortable bringing that work into class because they know the work that I’ve written, which is entirely possible.

I’m hoping that is what “The Autobiography of My Novel” essay becomes. Somebody, a friend of mine who teaches writing last night was telling me that she had been able to give it to a student of hers who hadn’t been able to figure out the approach that they wanted to make towards writing about it. And that meant a lot to me. That this student wasn’t going to take my approach, but that reading about my approach had helped her figure out hers. That’s an ideal, to me, an ideal scenario for that essay.

At what point would you say you went from pursuing being a writer to feeling like you were one?

It’s an interesting question. I did something with my first novel that I think a lot of debut novelists do, which is they act as if it was a freak accident that they wrote it. They sort of disown it or whatever. When they’re like, well, you know, I don’t really know I did that, even though they worked for years to get the book done, get the book out. All of that. They don’t claim the victory. It somehow feels obnoxious to them or that they’re being a dick, or whatever sort of class background they come from doesn’t allow them to have that celebration or who knows.

I remember when I got my galleys, I was at a cafe in the East Village and there were these women sitting next to us and one of them was saying, “I’m so sick of how every waiter has a project here.” I’d been waiting tables for years to finish my novel. My friend came who had not heard them talking and I brought out my book to show her. I was like all those years of waiting tables finally paid off. And they just sort of shriveled into the wind. But in any case, I acted like after the second novel was finished, then I would really be a writer, as if somehow the first one didn’t count.

It was a terrible thing to do to myself. I see a lot of people do it and I try to warn against it when I see it. It’s sort of like tying your hands behind your back as you go into the next race instead of giving yourself the full power of what you’ve learned. I did have a crisis of faith after the publication of Edinburgh where I did think, I don’t know if I want to do this again. I went out to LA. I had what I call an early mid-life crisis— lived in a sublet with an old flame, which is a terrible mistake. Drove a borrowed Porsche around— his— and gradually made my way back to the The Queen of the Night, the second book, but I gave myself a couple of months just to be like, what happened to me? What happened in my life? Is this what I want?

I think that’s the thing, is that you could give up at any point, that’s really the weird part. Or you can say no, I’m really a writer and then like a year later be like fuck this. And I think, you know, we are really always choosing to go back in with each book, in a sense, whether or not we are aware of it. I will say that like with the publication of this book of essays, I feel like I’ve reached a different point in my career somehow where I’m like, okay, all this is happening and I love going to events now and seeing my three books, but it’s taken a while to get to that place. Even well into the writing of the second novel, years of doing it, I was just not feeling like I had completely owned it and aware that was a problem and trying to think about why that was true. So yeah, I don’t know if it ever showed to anybody but that’s what it felt like on the inside.