The Golden Playwright – a conversation with David Henry Hwang

by Carla Stockton

David Henry Hwang (Columbia Univerity School of the Arts Website)

I am on the phone with David Henry Hwang, the Concentration Head of the Playwriting program in the Drama Division of Columbia University’s School of the Arts, and I’ll admit it: I’m a nervous wreck. David’s affable manner, his warmth, his easy conversational tone should put me at ease, but omigod I’m talking to David Henry Hwang, the author of more great plays than most of us will see in a lifetime as well as screenplays, opera and musical theater libretti . . . he has even scripted Disney cartoon features and supervised the transition to a web mini-series of his play Yellowface. Nominated for three Tonys, he has won one, and he has twice been a finalist for a Pulitzer in drama and is the recipient of three OBIEs.

Awe has struck me.

There is a history here. Back in 2001, as I searched for the perfect musical for the spring production I had been hired to direct in a suburban Connecticut school, I read in Variety that Hwang had rehabilitated the book of Rogers and Hammerstein’s The Flower Drum Song. The article, by Steven Oxman, explained that Hwang had transformed the embarrassingly stereotyped Asian Americans depicted in the book Hammerstein wrote with Joseph Fields and had reimagined and adapted the story. Hwang re-set the play in both China and San Francisco, gave it a political context, and eliminated the arranged marriage on which the premise of the original script depended. “Hwang manages to have it both ways,” Oxman wrote, “commenting on the entertainment while still delivering it.” I found myself nodding.

What made me love M Butterfly and F.O.B. (it stands for Fresh Off boat) and The Golden Child were David Henry Hwang’s astute commentary on and delivery of the entertainment along with his sharply honed satirical observations. This Flower Drum Song had to be good, a great learning experience for the students in the production I was to direct.

Besides, my kids would be just as impressed as I was. Hwang is no mere playwright. He is the idol of rock stars. No kidding. PRINCE was a fan. Interviewed by Broadway World Magazine in 2016, Hwang effused, “So imagine my groupie heart in 1989, when I opened PEOPLE Magazine to find a picture of Prince, coming out of M. BUTTERFLY, my Broadway show! Prince goes to Broadway? Who knew? He saw my play!”

Apparently, Prince was considering adding a Broadway musical to his credits, and he summoned the playwright to his hotel suite to confer on the prospect of collaboration. That project never materialized, but Hwang did pen the lyics to Solo, which appears on the album Come and is the B side of the single Let it Go.

No question about it. The kids would beg me to find a way to get David Henry Hwang to come to Connecticut to see the definitive youth production of his version of The Flower Drum Song.

It wasn’t until after I’d read the perusal (from the R & H Library, which handles permissions for the entire canon) that reality hit me.

It was 2002. Suburban Connecticut. There were not nearly enough Asians in the school to cast eight Asian leads and a full chorus of singing/dancing Asian kids. And there was no way I would cast the play with white kids. I had seen enough interviews, read enough of Hwang’s essays to know that yellow facing – a practice that casts non-Asians in Asian roles – is one of his most fervent oppositions. It’s even the subject of one my favorite Hwang plays called Yellowface, which was adapted for the YOMYOMF network in two parts.

Mounting such a production would offend my sensibilities as much as doing Carousel, which features a woman singing “He’s yer feller and you love him, that’s all there is to that” about a man who has just assaulted her. No way.

Full disclosure here –Paul Muni, the Polish Jewish actor who played Wang, the farmer, in The Good Earth, was my grandfather’s first cousin.

The Good Earth – MGM Trailer Still

This is a fact that makes me squirm, especially because, like Hwang, I am the of the first generation of children born in America, and I was always troubled by Hollywood’s habitual casting of actors such as Sal Mineo or Robert DeNiro or Charlton Hestons to play Jewish characters. Those were roles that should have gone to any of the myriad Jewish actors in Hollywood and New York, who instead changed their names and lightened their hair and skin so they could play WASPS . . . or who altered their appearances to play the less desirable ethnic roles. Most offensive to me was the practice, illustrated by Muni’s Wang, of painting eye slants and yellow skin tones, hence the term yellow facing .

On the phone with David Henry Hwang, there’s a bit of a silence between us for a moment, but I swear I can hear his eyes crinkle into a smile as I describe my relationship to Muni. It was a good place to start. I was trying to get my breath back, to relax into this. I’ve interviewed people I admire before, but, again, this is David Henry Hwang!

It’s going to be okay. This guy’s a mensch. I had asked him earlier if he liked being at Columbia, and he said he loves being a professor and a mentor, guiding new talent. It shows in his demeanor, the gentle encouragement that easily finds its way to my ear.

This is not actually the first time we’ve “talked.” David Hwang and I have “met”a few times. . . on Twitter, of all places. In October, after I attended a panel he was on called Convergence/Divergence, I tweeted: The gr8 David Henry Hwang says, ‘Hamilton the musical play of my generation. Perhaps the musical of the millennium.” And to my delighted surprise, he replied, “Anyone who can rhyme Rochambeau with go man go is genius in my book.”

I was not surprised that what struck him most about Lin-Manuel Miranda’s brilliant musical built around linguistic gymnastics was the language itself. The things I always notice when I read Hwang’s work, echoed now in his voice, are his remarkable economy with language, reinforced by his genius for juxtaposition of sound and usage. His voice is animated and engaged. Language is an instrument he clearly loves to play.

I ask him to talk about translation. One of Hwang’s more notable credits is an adaptation of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt though he doesn’t speak Norwegian. This version updates and Anglifies the metaphors, relies heavily on contemporary American references to re-tell Ibsen’s version of the Norwegian Everyman. In literary translation, fluency in the original language is far less important than fluidity in the language of the translation.

He tells me that the actual translation, the literal transfer from Norwegian to English, was executed by Director Stephan Muller.

“What I did was craft the language.” Here he stops to measure his words. “The trickiest thing is understanding the role of idiom and cultural context. What do the people do and say in the language or in the culture in which the play is written, and how is that translated into the language and the culture in which the play is being performed. Then its about the economy of the performance language . That’s the critical piece. “

“You see that exemplified in translations of musicals or opera. When I’ve had musicals translated into languages, that’s been interesting, especially at Disney. Disney was very controlling about the translation. They had strict guidelines. They’d contract a literary translation but at the same time hire someone to do a literal back translation, which, theoretically, should be more accurate and provide for authentication. But it doesn’t come close. Because in that case all the idioms go away. Idioms are uninterpretable.”

Translators must consider how each language uses metaphors and idioms differently for even the most trivial of matters. It may make sense, for example, to the Chinese mind, to refer to undisturbed grass as “sleeping,” but the phrase won’t work in English. By the same token, English phrases like nest egg and bad egg have no correlative in Chinese, and the literal translations can have ridiculous, humorous, even disastrous effect.

Which is the central preoccupation of Hwang’s play Chinglish, which I saw at the Longacre Theatre in 2011. Directed by Leigh Silverman, the slapstick linguistics dramatize the way people communicate and fail to communicate across cultural expanses, the way humans are desperate to be understood but fail to understand. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PpP2UIH8U1Y)

The play, delivered in both English and Mandarin, features super-titling that lets the audience in on the super-joke: every time a statement emerges, it is intercepted by a mutilating misinterpretation. It’s the manifestation of the experience of knowing the language of a foreign film or an opera and reading the subtitles only to find that the audience is being thoroughly misled. Classic David Henry Hwang virtuosity. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LEaLxLdVhv4)

It strikes me as we are talking that several of Hwang’s plays, including Golden Child, Kung Fu (an homage to Bruce Lee), Yellow Face and Chinglish, have been directed by Leigh Silverman, one of the too few women breaking through the glass ceiling in New York theater (Silverman and Hwang).

“Your women,” I venture, “are so well developed, so fully realized. They’re witty, clever, creative, real. And you often work with female directors, producers. Clearly, your collaborations have been successful. So to what do you attribute the underrepresentation of women in theater and film?”

He takes his time answering. “You know, it’s part of that other conversation, the bigger discussion about the underrepresentation of ethnicities, the way yellow facing was a way of keeping theater white. We need to make a theater that looks more like America, one that is more about inclusion, which is just as much about gender as it is about race. In the same way that we need more racially true characters and creators, we need more and better women characters, women creators.

“Here’s the problem, and it comes down to money. Perhaps the greatest impediment to diversity – and this is true in ANY industry – is that bosses and administrators, the people in charge, tend to hire people who look like them. In theater, they haven’t begun to hire people who look like the audience. The audience has not demanded it yet. People continue to buy tickets even though they are not seeing themselves represented onstage or in the credits.

“I appreciate that you like my female characters, but I don’t really help things. My creating good female characters is not the same as having more female writers doing that. What sets women apart from other minorities is that women are already the majority of theater audiences. They need to stop buying tickets until they see better female representation. There is no shortage of talent among the women out there. Women need to demand to see more of them. That’s how they affect the change. It’s up to them.”

We agree that television is leading the charge in this area, and that reminds me that Hwang has recently become involved in writing for television, a medium serious writers used to shy away from. I wonder what kind of writing he prefers.

So I ask, “ Which medium do you prefer to work in?”

This time he doesn’t even take a breath before answering.

“All mediums are divergent and each has advantages and disadvantages, but

theater is my favorite form. It’s the most personal, has the fewest restrictions to self-expression, and I have the most control or at least the most sense of control as the primary artist, the primary vision, the primary source of the product.

“Then again, I have found that I can take joy in someone else’s project, and I can be very comfortable in collaboration, and this is true for everything from Glass operas to Disney films to The Affair.”

I keep to myself that I blame the presence of his name on The Affair credits for my having discovered it, which has led me into an addiction that has left me hungry for Season 3.

“ I had never worked on a TV show before,” he goes on. “ I find that I am loving being in the writers’ room at The Affair. . . . I came into it because I was trying to create my own show, and Sarah Treem was a former mentee who had become a dear friend, and she suggested I come work for her and learn from The Affair what makes a television show. So my mentee became my boss, and I am glad to say I am back on for Season 3.”

Be still my heart.

Technically, I have run out of time now, but my generous subject says we have time for a few more questions.

“Back in October, at the Convergence/Divergence Panel, someone asked if the theater is dead, and after a complicated but very wise reply, you said that the infusion of electronic media would breathe new life into the theater, that that is where the future of theater is. Can you explain what you meant?”

“You know . . . I’m not exactly sure what I meant then. I do know that theater has greatly benefitted from the digital age whereas some electronic modes, like music, have suffered from it. Live entertainment flourishes because digital performances are easily pirated while live performance is unreproduceable. That makes live shows more valuable than ever. You can’t experience being at a rock concert without being there, and you can’t experience being at a live play without being there. That increases the value. Prince figured that out years ago when he gave away CDs at his concerts. He knew that the CDs would be the best enticement to bring people into the venues for his concerts.

“Also, the presence of the electronic media heightens reality, makes what is live more alive. We need to find ways to make the live experience more interactive, and electronic media enables that.

“Sports events are finding the same thing. There is no more need to black out events the way they used to. The televised version enhances live sales and vice versa. They help each other.”

He stops and breathes. “Go ahead,” he encourages. “Ask me more. This is fun.”

“I do have two more questions if you don’t mind.”

“Shoot.”

“If you could change one thing about the theater – “

“Nope. I can’t choose one thing. I’d have to have two at minimum.”

“Okay. Two then. What are they?”

“Okay. First – Ticket prices – How can we make theater accessible to a larger number of people if we allow the ticket prices to be so high? The business model is the problem. That needs to change.

“ And also the inclusion thing. We must create an American theater that looks more like America. Like I said it’s not an issue that’s specific to theater. By 2040 minorities – particularly Asian – will be the plurality, no longer minority. This also speaks to accessibility, don’t you think? Theater is less accessible to those who are excluded. What’s the other one?”

“Do you have a favorite work?”

He laughs again. “Look. I’m a father. I’ll use the kids analogy. I have three kids, and I love them all equally. With each, however, I have a particular relationship, just like I do with everything I write. F.O.B. was my first play, before I even knew how to read plays or write them. It will always be my first. Some of my plays are overachievers, others are misunderstood. I love them all. “

After I hang up, I imagine shaking his hand and thinking, “I’ll never wash that hand again.”

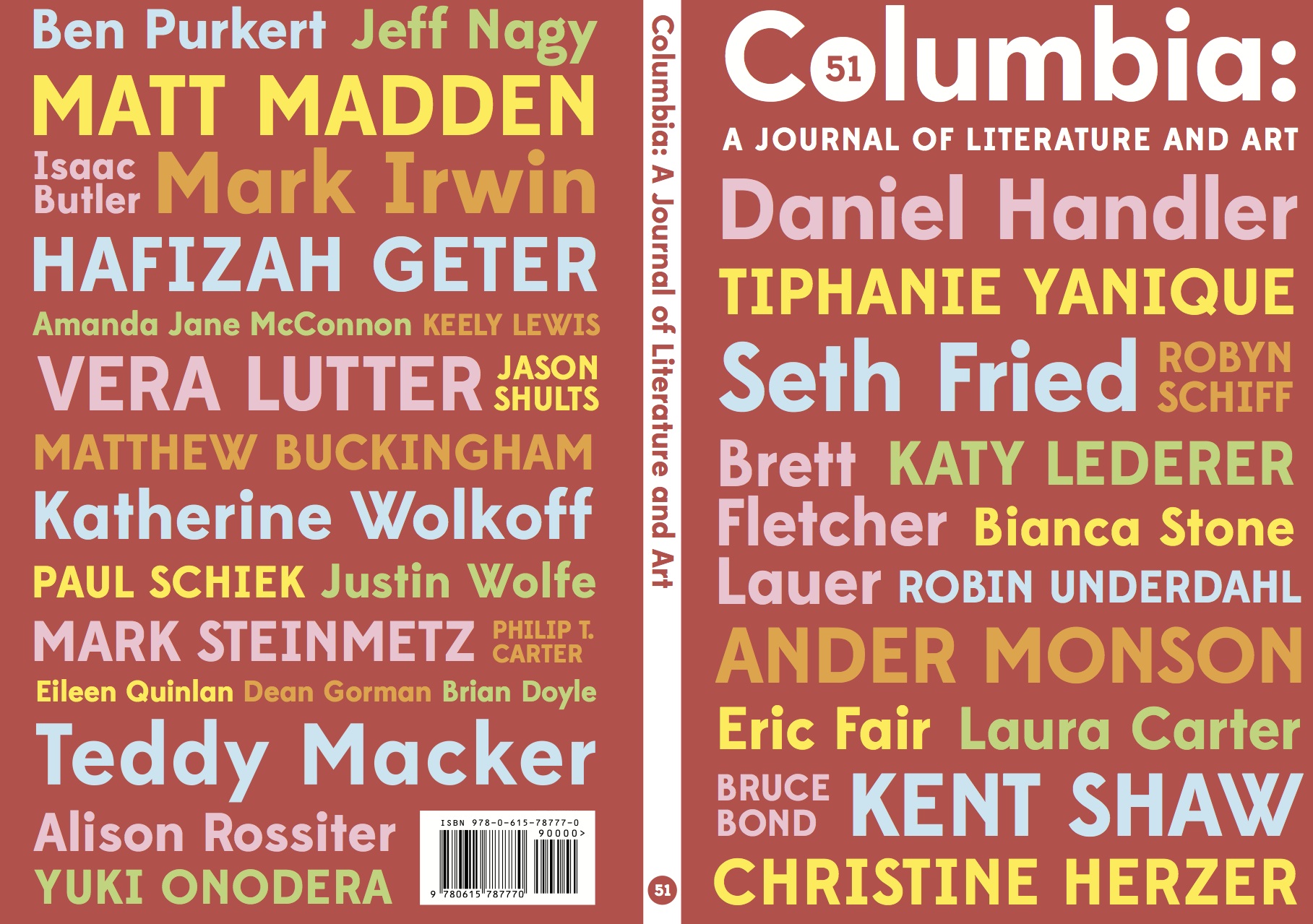

Dear readers: This will be the last installment of GET REAL in Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art online. I have been invited to move it to a new site, and I am excited about the move, which I will announce soon on my FB Writer’s page https://www.facebook.com/CarlasWrite/ as well as on my blogsite: carlastockton.me. I’d love to hear from you. . . . Thanks for following me here. See you around! Carla Stockton