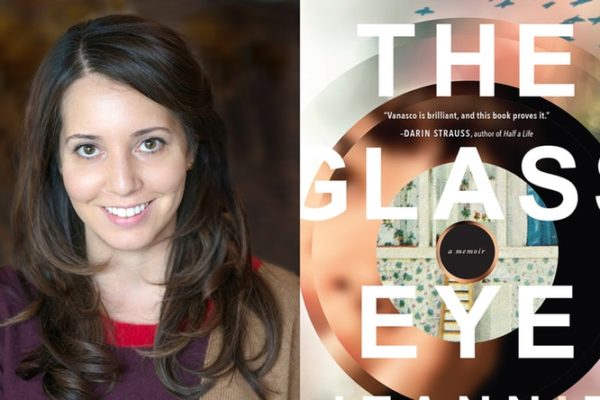

photo cred: Bustle

When I read Jeanne Vanasco’s debut memoir, The Glass Eye (Tin House, 2017), the book left me crying on a subway train in Brooklyn.

When I met with the author at Shakespeare and Co. Bookstore, a week after the release of The Glass Eye and told her so, Vanasco, an Ohio-native now based in Baltimore where she teaches creative writing at Towson University, said, “That means a lot to me, though it’s still so strange to hear that.” We sat in the bookstore’s cafe, across the street from Hunter College (CUNY), where Vanasco workshopped earlier drafts of her memoir as an MFA Creative Nonfiction student.

Daphne Palasi Andreades: How did you decide on the memoir form? At your book launch at Greenlight, you mentioned that you’d trained as a journalist and also as a poet. So why a memoir?

Jeannie Vanasco: For a long time, I thought of memoirs as something that people with bad childhoods wrote, or something that famous people wrote. I remember seeing a memoir “by” Paris Hilton’s dog, Tinkerbell, at a Barnes and Noble when I was in undergrad. I was like, “Goddamnit, Tinkerbell has a book?” (laughs) Originally I went to college to study journalism. Then, roughly a month after classes started, my dad died. I promised him, on his deathbed, that I’d write a book for him. I don’t know where the promise came from. I’d already wanted to be a writer. But the promise definitely made writing a book feel more pressing. I thought I’d write a novel or a poetry collection someday. Memoir didn’t cross my mind. To major in creative writing at Northwestern, you had to apply to the writing program your sophomore year. The English department offered two tracks back then: poetry and fiction. I ended up doing both. There wasn’t a nonfiction track, but now there is. It started shortly after I graduated. I think Eula Biss runs it.

DPA: I love her! “The Pain Scale.”

JV: Me too! Every time I go to the hospital and a doctor asks me, “On a scale of one to ten,” I want to bring up that essay. I wish I could have studied with her. But I had great poetry and fiction professors whose writing I often return to: John Keene, Reg Gibbons, and Robyn Schiff, to name just a few of them. But I remember this one visiting professor criticizing The Kiss, a memoir about Kathryn Harrison’s incestuous relationship with her father. Kathryn had already written fiction, and the professor, who I still respect tremendously, told the class, “Why did it have to be nonfiction? Why didn’t she write it as fiction?” I think that’s when I internalized this idea of fiction and poetry being the higher, more literary forms. I wanted the book that I wrote for my dad to be artful, where it wasn’t just about the story, but about how the story was told.

DPA: At your Greenlight book launch, you mentioned the influence of poetry on your writing in terms of wanting the language to have a sonic quality and the “plot” to be able to make associative leaps. At the same time, in the meta sections of book, you show yourself thinking, “This sentence sounds really pretty, but I don’t know if this is accurate.”

JV: I didn’t want a sentence’s acoustics to interfere with its accuracy. The meta sections let me keep some of the poetic sentences that I liked, sentences like: “I tried not to hear her name when he said my own.” I questioned its integrity, and so I couldn’t include it, ethically, if I didn’t explain my hesitance to include it. With the meta sections, I wanted to express my unreliability without being unreliable.

DPA: I loved those meta sections because it wasn’t a technique that I’d seen in other memoirs before—what a risk and an experiment! I said to myself, “I don’t even know if I have process questions to ask Jeannie,” because of how you discuss your process in the book using those sections: from the logistics of you showing yourself putting your binders together to organize your research, discussing your fears about writing, and also how you felt at the time. At the same time, those sections seemed integral to the story.

JV: Early on I wanted the memoir to be about the struggle to write the memoir. After all, I’d organized my entire adult life around the promise to write a book for my dad. But a professor in grad school said, “You can’t write a book about writing the book.” Don’t get me wrong. I had great professors at Hunter College—including Kathryn Harrison—and I understand where this professor was coming from. Overall, she was a great teacher. She told me that I over-intellectualized when I should have been generating scenes. And she was right. This is why teaching creative writing is so hard. You only can go off what’s on the page. You don’t know the hidden transformations happening in the student’s brain. When I first spoke with Masie Cochran, my editor, she said, “The Glass Eye is about your dad, but it’s also about trying to write the book for your dad,” and I was like, “I love you.” (laughs) So we restructured the book. My deathbed promise to my dad—that part moved to the very beginning. By foregrounding the promise, it allowed me to include those meta sections. Then again, even using the word “allowed” makes me uncomfortable—I think anything can be permitted.

DPA: Elissa Schappell says, “You can do whatever the fuck you want in writing,” just do it well.

JV: Exactly! The meta sections, those are just hindsight perspective. In memoir, you’re talking to a reader. You’re not trying to trick the reader into being “in” the story and forgetting that you, the author, is present. That said, I’ve always preferred fiction told in the first person. Fiction that’s sort of memoiristic. John Darnielle’s Wolf in White Van has that feel. With that novel, you know from the beginning what happened. The story is really the narrator’s reflection on what happened. A lot of times, I want to know who’s talking, or I want to know the book’s reason for being; I want it woven into the story in some way. Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, for example, is a collection of letters to the narrator’s son. That’s not to say I don’t like the third-person in fiction. I especially like memoirs that play around with the third-person, like Louise Krug’s Louise: Amended and Paul Auster’s The Invention of Solitude. My book’s meta sections remind the reader of the artifice—which, to me, was the most authentic thing I could do.

DPA: To me, those meta sections increased your narrative authority. It made me trust you to see you questioning, “Is this memory accurate? Did this happen? I don’t know, let me call my mom.”

JV: That’s reassuring to hear. A lot of those passages were lifted verbatim from my journals. While I was writing the memoir, I was trying to figure out my narrative present, and that was really stressful. I kept journals, documenting the writing experience. Going back to those—specifically when I was working most intensely on the memoir—revealed the book’s narrative present.

DPA: You mentioned how the language in earlier drafts was more lyrical and musical, and then you pared back from that. However, I was reading an older essay of yours on the Believer that featured some of the material from the book. I was struck by how different that Believer version felt from the final book since it had more emphasis on literary and historical happenings. In the published book, it felt more like you and your family—rather than the related historical research—are at the center. I was wondering about your revision process considering all of the different elements: paring back on the lyricism, then the pieces in the Believer, Masie’s editing of the manuscript…

JV: That’s a really good question. No one’s asked me about that, about how those essays in the Believer connect with The Glass Eye. I love the Believer’s aesthetic of integrating the personal with research, often concerning esoteric topics. I wrote those Believer essays on the side, while I was working on the memoir. I used the personal writing, the subject of my dad, as inspiration to pursue lesser-known stuff, like the portrayal of artificial eyes in fiction. I like when essays explore topics bordering on the academic, but I know why the author cares about the subject. I’d considered writing an essay collection with topics ranging from erasure literature to the history of necronyms—all grounded in my dad’s death. I wrote the Believer essays partly because I felt insecure writing memoir. I sort of saw the essays as their own thing. I didn’t know if I’d ever finish the memoir. A lot of times I pulled paragraphs from the memoir and integrated them into essays. I’d then let my curiosity explore the details by zooming out. For example, the house where I was raised had been cut in half and moved across town. I wondered: ‘How common was that?’ Then I discovered that Chicago’s urban landscape was deeply influenced by physically moving houses around the city. So I wrote an essay about 19th-century house-moving in Chicago.

DPA: As someone who’s an MFA student now, I laughed at the part where you have your creative nonfiction professor who pulls you aside after class and tells you what she thinks your book should be about. I thought, “Okay, maybe that professor was well-meaning, but she still misunderstood or was too imposing.” Being in workshop, I feel you encounter that dynamic all the time: people insisting what your writing should be. I was wondering how you found your vision for you book regardless of authority figures.

JV: I think it’s hard because a teacher’s vision for your work is inevitably shaped by larger entities: the publishing marketplace, for example. Publishing houses are businesses, and they often lose money on literary books. So the focus tends to be on the hook, or story. Whenever an agent would ask me, “What’s your elevator pitch?” I’d get so frustrated. My advice—to anyone interested in MFA programs—is to find a program where there’s faculty whose styles or voices are different from one another’s and your own. Don’t go to a school, for instance, where all of your professors write more traditional narratives when you want to write formally-inventive books. While it can be useful to take advice from writers whose aesthetic is different, I also think you need that balance of someone whose aesthetic is similar. Masie and I share the same taste in terms of authors and styles, and I’d read all the books she’d previously edited and I loved them, so it made sense to work with her. I had a professor tell me, “I don’t know if you have a book. Everyone’s parents die.” At the time though, I didn’t have the plot, I didn’t have the meta stuff, I didn’t have the hindsight perspective in there, so that professor’s point-of-view was valid based on what she was seeing. That’s what makes the workshop so hard, because your classmates and your professors are really going off what they’re seeing on the page, and sometimes we don’t articulate on the page exactly what we want to do—sometimes because of the rules, we think we can’t do certain things. I had some great classmates in my second-year at Hunter who were extraordinarily helpful, but it can be really hard when you have some people telling you don’t have a book. If I hadn’t been so determined to write a book for my dad, I don’t know if I would have shut down and moved onto another project. As a teacher now, I tell students, “My critique could be wrong. I don’t know what’s happening in your brain. You tell me where you see your writing going.” The MFA can be useful when you already have a vision for your project. Sometimes it’s bad to get advice too soon. Other points-of-view are fine. I don’t believe in the Western cultural myth of the sole creative genius. Early on, though, I think that listening to other people’s opinions can be detrimental—not only for the work, but for your own thinking.

DPA: I have a couple of friends in the MFA who say, “I just started a novel over the summer, and I don’t want to submit it to workshop because I don’t want anyone to kill my groove even though I know it’s not that great yet.” They just want to let their ideas come out on the page and then see what happens, which makes sense, because workshop can be discouraging.

JV: Yes, and it connects to why publishing houses like Tin House, McSweeney’s, New Directions, Graywolf, Catapult, and Two Dollar Radio are so important—because they provide a space for more inventive work, the non-traditional stuff that isn’t readily accepted at the bigger publishing houses. If you don’t see a place in the publishing world for your work—and that sort of argument can be extended beyond publishing—then you’ll likely feel constrained by the conventions. You might not pursue the writing that you want to do.

DPA: How did you end up deciding on an agent?

I’d gotten lots of mixed signals from agents. One invited me to Balthazar’s, and I thought: ‘she’s definitely going to sign me.’ Then I got there, and she told the hostess: “Oh, we’re just going to have coffee.” I mean, who goes to Balthazar’s for just coffee? So we got to our table, and she immediately said, “I don’t think this is the book, but would you consider doing general nonfiction on mental health and grief?” I said, “No, that’s a whole other book.” I already was feeling down about the project because it didn’t seem to fit with any of the agents I’d met. Several got excited at first, only to ask the same thing: “Can you turn this into general nonfiction?” The next day, I got an email from this agent, Victoria Marini. She said she’d read my essay looking at the portrayal of artificial eyes in literature on the Believer’s website. Victoria asked if I had a manuscript. I sent her the manuscript and a couple days later we met at a coffee shop in the West Village called The Grey Dog. I thought, ‘she’s not going to sign me, this is just a normal place’ (laughs). But Victoria, she came with all of these notes and all of these ideas. She was so enthusiastic—I think she had drawn pictures of how she saw the ARC looking! I signed with her. She’s fantastic.

DPA: I’ve heard professors talk about how, even when they sign with an agent or they sell their manuscript and the editor is working on it, there’s still so much that could wrong in that process. Like if they’ve signed with a bigger publishing house, and that publisher doesn’t care about marketing their book because they’re worried about all their other books. Tin House on the other hand—

JV: Is amazing. They did such a good job. Sabrina Wise, my publicist, has been phenomenal at getting the book out there. So has Nanci McCloskey. Sabrina even helped place an essay of mine in Modern Love. And she and Masie worked with me on edits before sending. The attention that they’ve given me—I feel very grateful.

DPA: I was even impressed by the book cover design. I noticed your handwriting because I remembered how it looked from when you signed my book. I was so impressed, it’s such a cool design.

JV: Diane Chonette, the art director, she’s brilliant. She captured what my process looks like. I couldn’t have asked for a better cover. You can’t make out too many of the words on the back cover, but the word “hindsight” is clearly there, which is something that’s so important to me. As for the front cover, it’s better than anything I would have asked for. The repeating circles evoke my elliptical, manic thinking. The flocks of scattering birds, my metaphor for my racing thoughts, fill much of the cover’s outskirts. The blurry and overlapping faces of the two girls suggest my obsession with Jeanne. Their faces are only partially visible. One might be a twin of the other, but you can’t tell. The patterned wallpaper of the dollhouse reminds me of the dollhouse that my dad made for me; he cared about its details, such as the wallpaper. He even built stairs for the dollhouse. On the cover are stairs, and I like the subtle though maybe unintended pun of stairs/stares. They lead into the central circle, the focal point, which reads “a memoir.” After I decided that The Glass Eye should be a memoir, my thoughts simultaneously came together and unraveled. Also, the central circle appears where one girl’s left eye would be. My dad lost his left eye to a rare disease, and as a child I once pretended that I couldn’t see out of my left eye—because I wanted to be like him. Instead of clicking together into a concrete visual image, all these fragments form a mood—just as I hope that my fragmented binder structure forms a mood. The cover’s color scheme captures the memoir’s different tones. It’s overwhelmingly light as opposed to dark. The contrasting shapes/lines direct your focus while also confusing it. The big typeface reminds me of an eye chart, but not glaringly so. The ‘i’ in my name appears in a slightly different color, almost disappearing into the circle behind it—which reminds me of how I often lost sight of my identity in the context of Jeanne. The cover is its own experience. It also feels essential to the reader’s experience of my book. Am I vain for marveling at my own cover for so long? It’s so beautiful. It’s hard to look away.

DPA: It’s amazing when all of those elements tie in together and are meaningful on the cover: the collage, your handwriting—

JV: There was just so much care put into it. It’s vain, but I wanted the cover to be nice! I know the old adage, “Don’t judge a book by it’s cover,” but people do! It’s a very real thing, and if a book doesn’t have an artful cover, someone may not take it seriously. Diane said she wanted the cover to be more “light” than dark because she saw the book as having “light” moments. Though other people said to me, “This book is too sad.” But I didn’t intend for it to be all sad. I did want some lightness.

DPA: There’s so much humor in the book, like you fostering kittens and trying to adopt pets during Hurricane Sandy, and Chris’s reaction.

JV: I did want there to be this shift where the story becomes increasingly lighter, where the shift in tone contributes to the plot. It’s interesting because you don’t have control over the book once it’s published, and people will have their own perceptions—that’s why I’m avoiding, or trying to avoid, internet commenters. A few of them have said, “I don’t think her health is better, I think she’s in denial; there’s not resolution at the end.” But I didn’t want perfect resolution because I don’t think that’s how life works, or how a mental illness works, where suddenly you’re cured.

DPA: There were two parts of the book that were particularly powerful for me: one where you discuss the moment when your half-sister Jeanne moves from being a “concept” for you (and us, the readers) to when you visit her grave, and you feel the full force of, “Oh my gosh, she was a person.” Another powerful moment was when you came back from the hospital and you’ve received the letter from your mom and we get to hear your mom’s perspective on her past marriage and meeting your dad. How did you decide to convey those extremely emotional scenes?

JV: There’s a difference between being self-aware and being self-absorbed. I didn’t want my experience of loss to be the only experience that I explored. I was thinking about my dad’s life and how hard it must have been to have a daughter die when she was sixteen, and to have his then-wife and his other children blame him. I was thinking about my half-sister Jeanne being a real girl. And then my mom—again, I’m not the only one who lost my dad—she was profoundly in grief. I wanted to expand the book so that you got a sense of other characters’ thoughts and feelings, not just my own. So the letter from my mom just seemed like something to include verbatim because it was so beautiful. I also wanted to give her a space to talk about her thoughts and feelings, where it wasn’t just about revealing information or checking my memory or “facts.” She told me that after I left for college and my dad died, and our dog died, she was all alone in the house. I did think about how sad she was that she was by herself, but I hadn’t considered this idea: that she also lost me because I wasn’t at home. Having these conversations with her made me rethink my perceptions of the story.

DPA: Do you feel you’ve fulfilled your promise to your dad?

JV: I tried to show how much I love him and what a great father he was. Maybe I don’t want to think that I fulfilled the promise because it gives me something else to work toward (laughs).

DPA: Last question: How are your cats doing? I just have to cover all my bases.

JV: Thank you! Flannery and Bishop are fantastic, but now both of them have three legs. Bishop developed this rare tumor on one of her front paws and had to have the leg removed. Flannery is missing her right hind leg. Bishop is missing her front right leg. She gets around just fine. In fact, she’s even better at destroying furniture with her nails. I’ve been researching the history of domesticated animals with disabilities, and that might be next, writing about animals with disabilities.

Daphne Palasi Andreades is currently an MFA Creative Writing candidate at Columbia University, with a concentration in fiction. She is from Queens, New York.