Review by Eli Hager

A strange thing happens in the Mississippi Delta in autumn. Most of the region’s famous cotton gets picked and wrapped up in plastic (work that’s done by machines now, not slaves or sharecroppers), but some of it slips free from the packaging. And at the end of each day one can see hundreds of furry white bolls–along the flat, flat, flat fields, or against the red ball of a sun and the flicker of heat lightning and a brutal storm coming–falling like hail from the sky.

I lived in Indianola, Mississippi last year, and the visual aesthetic of the place was just weird like that. Cypress, myrtle, magnolia trees sunk in swampwater; stray dogs limping along the curb; handwritten campaign signs and neon check-cashing and cash-advance storefronts; carports and columned homes and the wide gorgeous sunset. But none of it was strange as the cotton flying in the evening. I would see that and wonder whether history–that is, the cotton–was recycling itself, the way water does (evaporation, condensation, precipitation). I would wonder whether it was that great physical symbol of economy and injustice–again, the cotton–coming right back down onto my head.

*

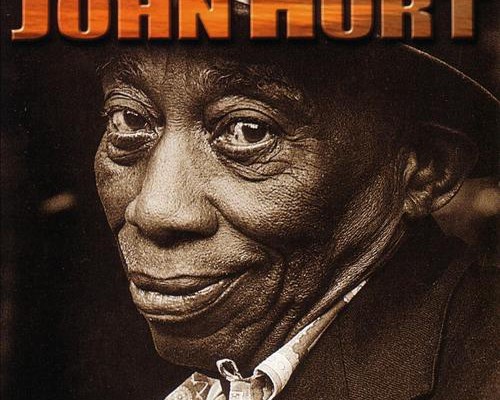

I’m setting this bizarre scene not because I’m indulging, not primarily at least, in the usual big, dreamy portrayal of the Mississippi Delta. I’m beginning here because I just finished the superlative album Mississippi John Hurt: Rediscovered, and it has me thinking again about Mississippi’s (and Mississippi is synecdoche for America) problematical relationship with cotton, the past, recycling and “rediscovery.”

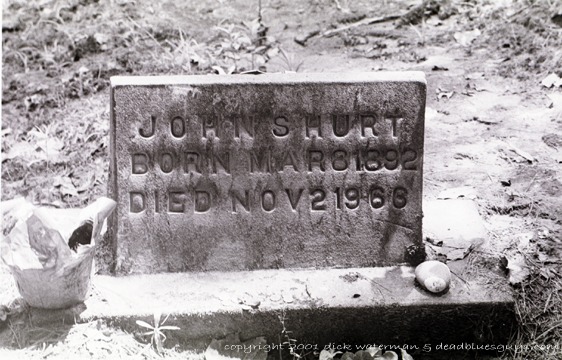

One key question is this: rediscovery by whom? John Hurt was born in either 1892 or 1893, according to the two gravestones of his that I found, and from age nine until his death in 1966 he split his time quite evenly between playing dances and working as a farmer. But he’d recorded for a major label just once (for Okeh in 1928), which to white blues fans outside the community meant his musical career was, instead, long since over. So, in 1963, an enthusiast named Tom Hoskins followed the lyrics of the song “Avalon, My Home Town” to the foothills of Carroll County, where he “found” an old man who sang like John Hurt and brought him to Washington, D.C. to be idolized, re-recorded, etc. etc.

What’s implied by the language of “rediscovery” is all very paternalistic, in almost the same way that tenant farming was: as if black artists and black workers exist only when (i.e. insofar as) white people can use or recognize them. But then again–and here’s where, maybe, I’m implicated–I’m so glad that the 1960s blues revival occurred. Surely, for one, Tom Hoskins’, Leonard Chess’, and John and Alan Lomax’s soft, liberal brand of bigotry was not the worst kind, nor was it without positive effect. Their efforts did pay bills for Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Leadbelly and John Hurt, and did give those sublime musicians an audience the sheer size of which conferred a measure of incontestable respect.

Moreover, it’s because of Tom Hoskins, the Library of Congress, Bob Dylan and all the coffeehouses and college campuses of the world that I (me!) get to hear that good music too. Speaking of which, let’s get to the songs, yeah? It’s not a matter of hyperbole or my romanticizing every last thing to say that “Coffee Blues” and “Since I’ve Laid My Burden Down” sound intimate, close–as if the singer’s lips are rubbing against the microphone. (In fact, according to Hurt, his producers did ask that he hold his mouth very still and very near to the microphone, and his “neck was just sore for days after.”) Nor is it white blues-boy-speak to add that the pickless fingerstyle guitar picking on “Stagolee” and “Candy Man” sounds like the work of six hands. Taken together, the singing and the guitar playing on this album will make you feel like a human being, no matter who you are, and that’s praise.

My feeling of proximity to John Hurt’s music is lyrical too, not just acoustic. (Given, some of this work is on loan from gospel and folk standards, but most is original, and all of it reflects Hurt’s inflection, pacing, and sense of what to keep in and keep out). What makes these lyrics so applicable, despite the fact that the explicit life experience described is not mine, is what I’d call their ambivalence. By that I mean that there’s real bad pain (“the sun gone down…my rest a stone”) but also hope (“yet in my songs I’ll be, nearer my God to thee”). There’s the proud independence of rural life and artistic integrity (“New York’s a good town, but it’s not for mine”), but also the recognizable desire to connect and to be listened to (“make me down a pallet on your floor”). That wavering, uncertain “blue note” is what I’ve always felt about the world and what I recognize, and it prevails over what’s otherwise my biographical ignorance.

And that’s what brings us back around to the theme of rediscovery and historical distance. At first, I was poking fun at the white blues revivalists for thinking they were an important or necessary audience of black blues music. But if you listen real close, real close, to John Hurt’s songs, you realize it’s neither Mississippians nor black people but everyone with a heart who’s the audience. These songs are about sex and love and weariness and violence and death and God. It’s perhaps most racializing and ridiculous of all to suggest that any of that is “intended for” one audience or another, or that there’s something somehow unethical about a new audience “discovering” themes they recognize.

*

That all sounds grand and vague again so let’s listen closely to “Monday Morning Blues” as a case study. This song, musically, is a straight blues: twelve bars, major seven chords, AAB lyrics, syncopation and terror and bliss and all the rest. Lyrically, the song’s about waking up for work, going to lay down in jail, leaving home, all that unfair and aching stuff–but Hurt revels in it and makes music out of it. To me, that transferral of injustice and pain (prison, labor, weariness) into the revelatory joy of sound is as relevant as it gets. It’s a moment, I think, I know well. It’s the moment right after the one when you think it’s all going to hell, when you remember you’ve got you, you’ve got art, and you smile.

That ambivalence–pain that yields to and sounds like triumph–is also the heartbeat of American music. Think of all the Jimmie Rodgers and country-and-western songs about cheating wives, broken homes, impounded cars and dead dogs and poverty and all that: songs that somehow end in joy or with a joke, songs that sound upbeat and are for dancing and having a real fine time.

Or think of “This Little Light of Mine,” about the tiniest bit of dignity in the darkest place becoming the biggest thing in the world; or think of “Amazing Grace,” which is about, well, grace. Think of the ecstatic coda to Bruce Springsteen’s “Thunder Road,” after beginning on such a lonely and rundown note. When John Hurt sings, with very intentional irony, as far as I can tell, “Mister change me a dollar, give me a lucky dime,” we get a funny but also quintessential moment in American music. Here, the psychic pain that injustice can inflict (only having a dollar, and only having the “mister” to valuate that dollar) is transformed into the working-class fun of making a request the mister’s economic system would find irrational. It’s the best “fuck that” this side of the implied answer to Dylan’s question, “How does it feel to be on your own?” (“It feels goood.”)

“Monday Morning Blues” is one reason among 24 on this album alone that I’m glad someone had the respect or disrespect or whatever-we’re-calling-it to go and “rediscover” John Hurt. There’s just so much to think about here, so much I relate to, so much that makes me feel good, so much that makes me laugh and cry, so much more than there is on albums by “people like me,” whatever that means, that I can’t help but think it’s good that I’m here listening.

*

Last year before I left Mississippi–I was a teacher, and my year was done, although my work wasn’t and there’s nothing I need to do more than go back–I drove to those two gravestones. They’re up in the hills in a way that most of that part of the world isn’t, and they’re hard to find. I curved up the rutted lane, and between the red trunks and branches I could see how flat the fields of cotton were down below me, how long and far the alluvial floodplain stretched out toward the Mississippi River.

On the stereo I was playing this album and it was ranging in the same way. There was the ragtime on “Funky Butt,” “Salty Dog,” and “It Ain’t Nobody’s Business,” dance music that was far more popular with the black audience at the time than the “deep” stuff that purists prefer now. There was gospel–a kind of music that to me seems more about being human and more honest about death than anything else I’ve heard–on “Nearer My God to Thee.” There was the straight blues and the jokey, personal stuff on “Coffee Blues” (“that loving spoonful” is a line that’s been borrowed a few times) and “Candy Man.” And then there were the stories, “Stagolee” and “Goodnight Irene,” about particular people, figures of the American pop imagination who seem somehow to incarnate all that we’ve ever figured out about violence, fear, justice, love, longing, humor, sleep, dreams and death.

John Hurt created a few of his own new figures of that sort. He also infused every element of his music– the broken chords on the twelve strings and the cracking and straining of his voice–with the sound of a living fighting subject working through the major themes. In the car (an Avalon) last year in Avalon, because of what I was listening to, I was working through all of it too.

Now at the top of the hill I got out and stretched and saw I had to go back in the pine and cedar woods, pushing through the thorns and getting cut around my ankles, to get into the cemetery. I found the markers for the Hurt family, and laughed when I found a can of Maxwell House and a huge bouquet of brand-new flowers. I stood there very still.

And then I reached into my pocket, remembering, and pulled out a poem I’d treasured and saved by one of my students, Jocelyn: a poem about getting her heart broken but wanting to tell about it. I read it again and then slipped it under the can of coffee, leaving it there, hoping only that very many people would love and listen to that girl’s voice the way I loved and listened to John Hurt’s and Muddy Water’s, and Faulkner’s and Shakespeare’s. I turned back toward the car to go and drive to New York City, and a single boll of woolly cotton lofted–and then another–from in between the trees.

Eli Hager is currently pursuing his M.F.A. in Fiction at Columbia University.