“Scent of the century”

Fragrance Foundation FiFi Awards, 2000

The perfume is called Joy, but the black box looked sinister to me as a kid, funereal; it looked like it should hold ashes, cigarettes, a lifeless heart. The perfume didn’t smell joyful to me, either—it smelled like sugar laced with poison. I couldn’t understand why my mother loved it so, why my father bought it for her so religiously—tiny bottles in a cushioned box, a larger bottle for extra special occasions. I was told it was expensive, rare, told it was the most generous gift, but it bothered me, felt like something between my parents I couldn’t access, some terrifying adult brand of joy.

**

Jean Patou journeyed to the South of France in 1926 to find a perfume that could recharge his haute couture business, hammered by the Great Depression. He didn’t like any of the samples Henri Alméras offered up, until the famous perfumer produced the yet unnamed Joy. “If you don’t like this,” he said, “I’ll get a job herding goats.”

**

The perfume smelled better on my mom; mixed with the heat of her body, it smelled less caustic, more like her, but even then, it made me shudder, made me feel a bit sick. She wore it when she went on dates with my dad, when my sister and I would weepingly chase them down the hall of our building, pressing the elevator button so the door would open again and they weren’t able to leave; we did this until the babysitter pulled us back to our apartment, where the Joy was still so heavy in the air, it closed my throat.

**

Patou loved the yet-unnamed Joy, but Alméras warned him it would be wildly expensive to produce. Patou’s confidante, society columnist Elise Maxwell, perked up and said that could be their whole shtick. They’d market it as the costliest perfume in the world.

**

When I was nine or ten, I formed a girl out of green clay, those little cylinders that come stuck together in a pack, that smell of glue and soil. I shaped a dress with a collar, shaped two little feet with shoelaces, hair that curled into a flip. I had never sculpted anything so lifelike before. I was proud of it and stuck it inside one of the gold boxes that had held Joy—so much better than the black Joy boxes, a J and P curled into a kind of yin yang on the top, a box that snapped open like a book—for safe keeping. I didn’t realize I had created a golem of sorts, the word Joy imprinted on her forehead by the phantom scent of the perfume, the word Joy slipping inside the girl’s closed mouth, beneath her invisible tongue.

**

Each ounce of Joy, it is said, contains 10, 600 jasmine flowers, and 28 dozen roses—the Damascene rose from Bulgaria, the Rose de Mai and jasminum grandiflorum from Grasse in the South of France. Joy smelled chemical to me, something made in a science lab; I was surprised to learn it was made of real flowers, whole fields crushed into gold.

**

I’ve never been a perfume person—it tends to make my eyes water, constrict my breath—but I did dabble a bit when I was young. I still remember how a sample vial of “Rain”—a natural perfume, perhaps a mix of essential oils—smelled at a shop near my junior high that sold locally handmade goods; I never purchased it, but twisted the brown bottle open whenever I visited the store with my friends. They would smell each tiny vial in the row of artisanal perfumes, and I’d stick to “Rain”, would inhale it until its scent filled my whole body, would put a dab behind my ears, rub some between my inner wrists like I’d heard you’re supposed to do—something about the skin being thinner there, more porous. The slick of fragrance didn’t smell like petrichor, one of my favorite scents, but it did have an essential raininess to it, deep and sweet and wet. I loved walking into the world with it on my skin, though not enough to ever purchase it. I didn’t feel ready to own the scent, somehow; it was enough to play at the thought of being a girl who wore perfume, to pretend to be a girl who smelled like Rain.

**

Of course it didn’t make sense to sell an expensive perfume during the Depression, but Patou found a way to make it work. He sent free bottles of Joy to 250 prominent American women in 1930, telling them “’If you can’t afford our couture, we know you’ll still want something desirable.” Perfume as a dose of luxury during lean times. This was nine years before my mother was born, but she must have absorbed the message somehow. She grew up in a blue collar household, and longed for a life of glamor. My dad was able to give her a taste of the world she wanted, bringing her to nice restaurants, to the theater, to the opera, but it was never enough. She wanted to buy houses we couldn’t afford, wanted to shop at Saks Fifth Avenue even after my dad’s direct mail marketing company went bankrupt. When her delusional disorder surfaced, it seemed fitting that her delusions were centered around money, that she believed my dad was hiding millions of dollars from her, money that could have kept her swimming in Joy.

**

I associate Joy exclusively with my mom, but of course she was not the only person to wear it. Marilyn Monroe, Vivian Leigh, Josephine Baker, Jackie Kennedy, Wallis Simpson, Gloria Swanson, Queen Elizabeth, Audrey Hepburn (who people sometimes mistook my mom for when she was young) and other celebrities favored the scent. Keith Richards reportedly used it as deodorant. I imagine my mom felt like a celebrity, felt like royalty, when she wore it, someone swathed in rarified air.

**

The first perfume I ever bought (and, now that I think about it, only perfume I’d ever bought until just recently)—was the ubiquitous Love’s Baby Soft when I was twelve or thirteen. All the girls I knew reeked of it, as did the girls’ locker room at school. Love’s Baby Soft came in what looked like a bottle of pink juice with a rounded pink plastic top, and had a cotton-candy-like scent. The slogan plastered on their ads in the pages of Tiger Beat and Seventeen Magazine—“Because innocence is sexier than you think”—was (horrifyingly) accompanied by a glamour shot of a girl who appeared to be about nine years old clutching a teddy bear, lipstick on her pouty mouth, hair coiffed in a pageant do. I worried about this girl whenever I saw this ad, worried about who considered her sexy, about what that person must have done to her. Her face looked vacant, haunted. I wasn’t ready for anyone to consider me sexy, but I was curious to know what sexiness would feel like inside myself, wanted to carry it under my girl skin like a secret fragrance only I could smell.

**

Joy is not just made of roses and jasmine from Grasse. According to parfumo.com, it has top notes of aldehydes, green notes, peach, rose, tuberose, and ylang-ylang, heart notes of orris root, jasmine, lily-of-the-valley, orchid, and rose, and base notes of musk, sandalwood, and civet. I hadn’t realized perfumes have top, heart, and base notes; I envy those who can detect them, just as I envy those who can detect all the different notes of wine. I just know whether or not any given perfume or wine makes me wince.

**

I was surprised to learn on parfumo.net that Love’s Baby Soft shares rose and jasmine heart notes with Joy, though certainly not the same quantity or quality of those blossoms (if Love’s Baby Soft even uses real blossoms). It also holds lily-of-the-valley at its heart, with top notes of lemon leaf and orange, and base notes of sandalwood, vanilla, “powdery notes”, and musk. Apparently the perfume is supposed to smell like clean babies—that was the perfume’s whole creepy 70s deal, making girls and women smell like sexy babies. Powder and musk.

**

I did like the smell of Joy body powder, liked the big soft powder puff inside the round black box that sat on the tank of my parents’ toilet—that powder smelled like pulverized Sweet Tarts to me, Sweet Tarts and the scratch-and-sniff flowers from Pat the Bunny. Joy for Kids.

**

In Perfume: An A-Z Guide, Luca Turin writes “To call Joy a floral is to misunderstand it, since the whole point of its formula…was to achieve the platonic ideal of a flower, not one earthly manifestation.”

**

Maybe the golden box that holds the green girl, the golem, is a cryogenic chamber of sorts, keeping my childhood alive there, intact. Platonic.

**

About a year ago, I happened upon a magazine ad for Joy, Jennifer Lawrence in a swimming pool up to her neck, not looking very joyful. In fact, her face looked more like the sexy little girl in the Love’s Baby Soft ad, slightly vacant and haunted, her lips parted in a way that was clearly supposed to be sexy, but struck me more as incomprehension. The cylindrical bottle of Joy in the corner of the ad didn’t look like the Joy I knew—it looked more like Love’s Baby Soft, in fact, the perfume pink, not the gold my mother loved. “Dior” was written in the middle of the O of JOY, which surprised me—could two companies have a perfume by the same name? I did a quick search and learned that Jean Patou’s company had gone through a few different owners—it was purchased by Proctor & Gamble in 2001, then by Designer Parfums in 2011, and by LMVH in 2018. LMVH which also owns Dior, released the new Joy, with a new scent, under that label the same year.

**

When I was a freshman in high school, I participated in a service club that sent busloads of mostly white students from our tony North Shore suburbs to tutor kids at a community center in a Latinx neighborhood of Chicago every weekend. I became friendly with the eight year old boy I tutored, and—even though this was likely not something my school would have endorsed—invited him to my house. When we picked him up, he was wearing a button down shirt and had his hair slicked back, as if he was going someplace fancy, not our aluminum sided house, where we would slide, screaming with laughter, down the basement stairs together on a foam chair that unfolded into a small bed, over and over again. His mother, who didn’t speak English, smiled and handed me a wrapped box containing an Avon gift set of jasmine-scented perfume, lotion, and powder. It felt romantic, somehow, like I was going on a date with both her and her dressed up eight year old son. The jasmine set sat untouched in my bathroom cabinet for months until I started having periods and didn’t tell anyone—I didn’t tell my mother for over a year—and used the jasmine perfume to mask the scent of the blood on the pads I made out of wads of folded yellow Kleenex. I didn’t want my parents to know I was growing up, wanted to stay the green girl in the golden box forever.

**

In a press release, Dior perfumer François Demachy said “JOY by Dior expresses this remarkable feeling of joy by offering an olfactive interpretation of light. This perfume resembles certain pointillist paintings that are rich with a precise, yet not too obvious, technique. It is constructed with multiple nuances, a myriad of facets that lead to an expression that is clear and self-evident.” Most reviews were not nearly so rhapsodic nor cryptic, saying the perfume was nice, but paled in comparison to the iconic Patou original. The Colognoissuer writes “Joy by Dior is a good perfume put together via the perfume assembly line of focus groups and market research; as cynical as it gets, in other words.” Cynicism: the anthesis of joy.

**

Merriam-Webster defines joy as:

1a : the emotion evoked by well-being, success, or good fortune or by the prospect of possessing what one desires : DELIGHT

b : the expression or exhibition of such emotion : GAIETY

2 : a state of happiness or felicity : BLISS

3 : a source or cause of delight

I keep looking at the end of 1a, “the prospect of possessing what one desires”—is the desire for something more joyful than the possession of that thing? Did my mom find more joy in anticipating the gift of Joy than she did in the Joy, itself?

**

There is one moment in the Joy tv commercial with Jennifer Lawrence—a commercial otherwise filled with standard woman-swimming-in-a-ballgown perfume ad fare—that feels like real, not consumer-driven, joy, a moment where she spits a stream of pool water out of her mouth and bursts into laughter. Joy as silliness, as wildness, as DELIGHT, GAIETY, BLISS.

**

If I were to make my own blend of joyful scents, it would include the burnt sugar toastiness of the top of my newborns’ heads, the mustiness of old books, the chlorine/fish food tang of Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, the gasolined air of my childhood apartment’s garage, the orange-blossom-thick air near the experimental groves at UC Riverside, the sweetness of my mother’s poppyseed cake in the oven (her noodle kugel, too), the mineral scent of stones wet with lake water, the chilled rubber of my childhood ice rink’s floor, the beer soaked, incense-tinged, hallway of my college dorm, the clean warmth of my kids fresh from a bath, the spiced comfort of my husband’s chest, the sweet funk of a room after sex. I’d toss in other scents I love–some sage brush, some ginger, some honeydew and rosewater, the richness of my own blood unmasked. I’d toss in both Rain and rain.

**

My mom didn’t learn to swim until she was 40, but she became an avid swimmer from that point forward. If she went a day without swimming, she felt off, didn’t feel like herself. She would have enjoyed seeing Jennifer Lawrence in that pool—she liked perfume ads with pools, told me when I was 12 that in a commercial for Chanel No. 5, the shadow of a plane flying over a swimming pool was a metaphor for sex, which made me want to run away screaming. Still, I think she would have scoffed at the new Joy. She’d have said it doesn’t have the elegance of the original. Elegance was important to her. She’d have said the new perfume looks like it’s for a little girl, would have fixed me with a hard stare.

**

Maybe the green girl in the golden box is my stunted self. Maybe that golem held onto me with her damp clay arms and kept me from fully growing up.

**

The new version of Joy has silver thread wrapped around its cap; the iconic 1930 Joy bottle, designed by architect Louis Süe, had golden thread around its neck. I had forgotten this detail, and when I saw the phrase “golden thread around its neck” as I researched the perfume, I shuddered. My mother died by suicide, cord around her neck in a random building named Golden Oaks. A devastating end to her quest for gold.

**

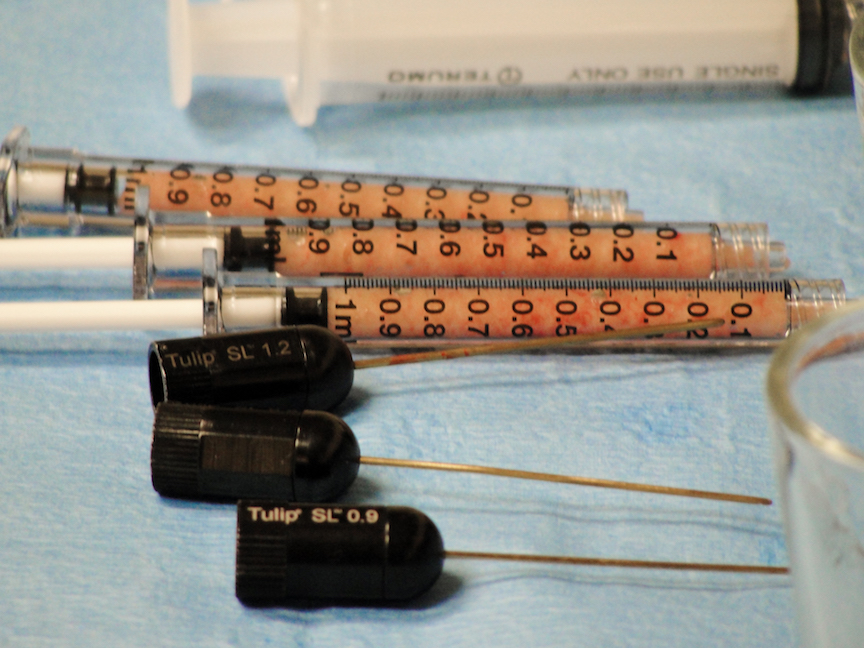

I ordered samples of the Patou Joy and the Dior Joy (the above-mentioned post Love’s Baby Soft perfume purchase) from a company that sells samples of various sizes, decanted from larger bottles. I ordered the smallest samples on the site—1 ml each. I knew I couldn’t handle more than that, knew I just wanted a whiff of each one. The Patou sample was $4.96, the Dior $3.49. The tiny vials arrived wrapped in a sheet of foam inside a silver net bag, along with a single espresso candy. Grown up candy. I only started drinking coffee, only started drinking wine, when I was 45, a few years after my mom’s suicide. Perhaps grief turned me into a real adult.

**

Maybe the green girl in the golden box is now the girl inside me who keeps returning to her mother’s death, the girl who thought she was done writing about her mother’s death, who thought this would be a piece about scent, not grief, but how could it not be about grief, the way scent is so evanescent, so connected with memory, so connected with her mother’s vanished body?

**

I was scared to open the vials of scent. I didn’t feel ready to smell my mom again, even though I was eager to get the last whiff I ever had of her—the stench of her death on the clothing we received in a paper bag from the coroner’s office—out of my brain. Maybe the perfume would knock that scent memory away. I could easily conjure up the smell of Joy, but the thought of actually having it in my nose again felt terrifying.

**

Jean Patou said “Just like men, perfume is never perfect right away; you have to let it seduce you,” but I don’t think a perfume could ever seduce me. Perfume is not my sexuality. It does the opposite of turn me on.

**

I opened the Dior Joy first, since I don’t have any emotion, any memory, connected with it. I tried to smell it once, with my sister, in the midst of a family reunion in Chicago to celebrate what would have been our dad’s 100th birthday. We went to Marshall Field’s, department store of our childhood, and I pointed out a gift set of Dior’s Joy on a shelf. We opened the white box, curious to know what this new Joy smelled like, but the box was empty.

**

Maybe the green girl in the golden box wasn’t afraid to grow up. Maybe she was just afraid to grow up and become her mother. Maybe that girl didn’t know there were other ways of being a woman in the world. Maybe it took her a while to learn this. Maybe it took her a while to figure out someday she’d be happy to be an adult, happy to recognize certain aspects of her mother inside her.

**

The stopper of the tiny vial was attached to a plastic stem that dipped into the perfume, like a slender bubble wand. I tipped my nose closer and almost instantly regretted it. There’s a reason I’ve been staying away from perfume—I’m allergic. I didn’t think to arm myself with antihistamines beforehand; what damage could one little whiff do? My throat immediately narrowed; my eyes started to burn. The perfume reminded me more of Love’s Baby Soft than Patou’s Joy, but with a more grown up bite. I couldn’t tell you the base notes, heart notes, or top notes, but I can say it transported me to my aunt’s perfumed bathroom, to childhood trips to the theater, engulfed in clashing layers of scent. I ripped open the espresso candy and popped it into my mouth, as if it could be a palate cleanser, could suck the fragrance from my nose, but of course that didn’t help. Even when I opened our sliding glass door, the scent remained.

**

The tagline in the original French ads for Joy was “le parfum le plus cher du monde”; not the most expensive perfume in the world—the most beloved.

**

I still haven’t opened the vial of Patou’s Joy. I haven’t felt ready to let that genie of the bottle, haven’t felt ready for the scent to linger in the air after I’ve had enough. Now it sits in my house like a tell tale heart, like a cyanide pill, like a time capsule I’m nervous to open, or maybe a time machine that could disrupt the world.

**

Maybe the green girl in the golden box is a golem of the little girl who would press the elevator button over and over as her parents tried to leave, Joy heavy in the air, wailing Don’t Go Don’t Go Don’t Go Don’t Go.