The global conversation around data privacy and the surveillance state has exploded in the past three years – keeping pace with dramatic developments in current facial recognition technologies. But in her recent novel, Little Eyes, triple Booker nominee Samanta Schweblin moves away from state-level conversations, instead examining our complicated relationship with surveillance on a personal level. Set in the very near future, she presents an opt-in surveillance community where little eyes are not only watching you, you’re fully aware and pay $279 for them to do so. Welcome to the latest global fad: the kentuki.

Imagine a Furby, but alive, and you’ll get a pretty good idea of what a kentuki is. With cameras for eyes and wheels for feet, the furry mechanical animals are described as little more than a cell phone on wheels, only in a cute skin. People who own kentukis are called “keepers”, and inside each kentuki is a “dweller”, controlled by a random, real person somewhere in the world via a computer screen. The control is limited; dwellers cannot do much besides move or purr. But despite this enforced silence, there is no chance that keepers might mistake their kentuki’s sentience for artificial intelligence. The terms of the kentuki are stated clearly on the packaging they come in: the connection is human. Also, mortal. If the kentuki runs out of battery (they run on three-day charge cycles) or if either party severs the connection, the kentuki dies – permanently. Purchasing a kentuki is tantamount to inviting a stranger into your house, to live and watch you in your most intimate moments. And everyone wants one.

What terms will we accept in exchange for a shot at emotional connection and companionship? In the unregulated gray area of online connection, how do we set and negotiate personal boundaries? These are some of the questions Schweblin asks, as the world is deftly established, kentukis are bought and sold, and the novel is set in motion. Structurally, Little Eyes unfolds in short, disparate stories, hovering over and flitting through different keeper/dweller narratives around the world, some of which are one-off, some of which recur. In the opening story, American teenage girls flash a kentuki, intending to tease the anonymous stranger residing in the toy – and are immediately blackmailed with their nudes. In another, a solitary old woman in Lima is gifted a dweller code by her Hong Kong based son, and becomes quickly attached to the German girl who owns her kentuki, conflating the affection her keeper shows the kentuki with affection for her. There is a kentuki liberation revolution, facilitating an Antiguan boy’s lifelong dream of seeing snow (in Norway). Two kentuki dwellers fall in love while their keepers hang out. It doesn’t take long for capitalism to blossom, and kentukis are profiled and trafficked to potential dwellers seeking specific emotional connections, to families, singles, the young, or old. The overall effect is the creation of a chilling, thrilling chorus of what the world might look like if the eyes watching us today were not big corporations looking to mine our data, but simply other curious humans, like us.

Schweblin is careful not to pin any blame on technology, and is more interested in examining the way technology expedites our existing anxieties around modern relationships, which are now invariably digitised in some form. The high price tag, clarified in the opening pages as “$279 – a lot of money”, reinforces the idea that opting in to the kentuki ecosystem is an active, thoughtful choice. Keepers, dwellers, everyone in Schweblin’s world knows exactly what they’re getting themselves into, and yet we see them repeatedly forgetting – or turning a deliberate blind eye to – the risks that come with allowing a stranger on the internet unchecked access to their inner lives. The fact that the kentuki creators never come into play shifts all culpability for events that occur within the novel from big corporations to human folly, and Schweblin’s cool, clinical prose refuses doing the work of interpretation for us, leaving the reader to draw their own learnings from the stage she’s set. Yet, at turns, our connections to the individual stories are severed, reminding us that we are ultimately guests in a narrative world of Schweblin’s making; engaging, but not wielding any real power in the way the world works.

Reading Little Eyes today is a surreal experience. The world we live in is not so distant to the one Schweblin posits, especially now, when we are all starved of regular human interaction due to the global COVID-19 lockdown. Even before the pandemic, we’ve willingly traded access to our data for connection and convenience. At present, we reside in a bubble of time where all our interactions are conducted over apps like Zoom and House Party, which have come under fire for data privacy and security issues. But we cannot just opt out, in the way that one of Schweblin’s characters could pull the plug on a kentuki connection. Real life is complex. Navigating the world today is deeply intertwined with technology, be it via GPS-enabled map, communicating with friends through social media or chatting applications, or digitising our photo memories online. The implications of incessant and invasive surveillance are in constant conflict with our basic need for social connection, compounded at present by the onset of a global pandemic that limits physical human interaction. Although the risks and terms of opting into these ecosystems are clear, our need for connection – even virtually – necessitates a kind of continuous, willful forgetting. It is perhaps the only option we have.

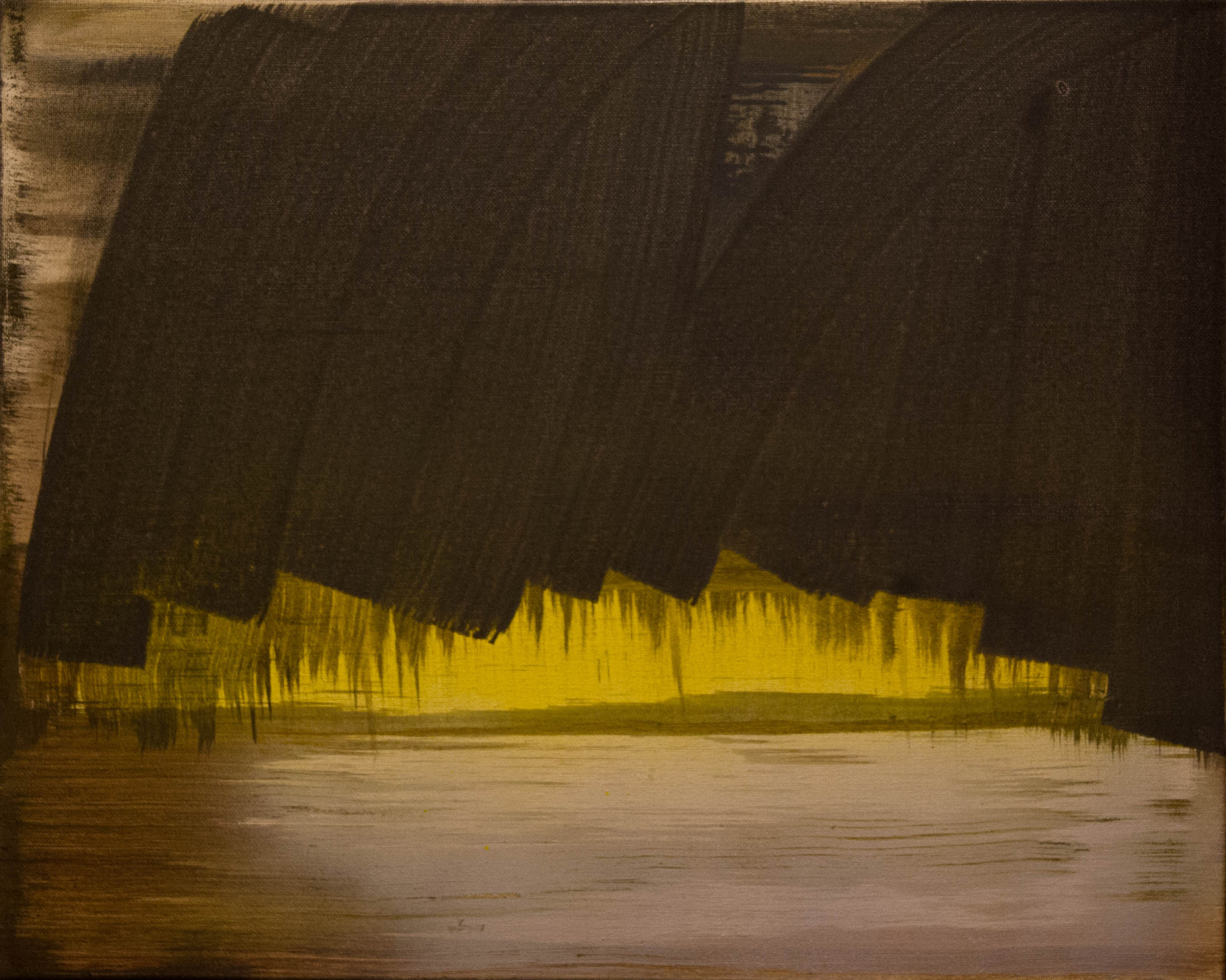

In 1984, Orwell described Big Brother as “always the eyes watching you”. Today, in Schweblin’s world and ours, we have gone one step further and invited Big Brother in for tea. We’ve just forgotten that this invitation is possibly unrecindable.