Review by Tomek Jedrowsk

—

“I am very attracted by bad taste–it is a lot more exciting than that supposed good taste which is nothing more than a standardized way of looking at things,” (Helmut Newton, 1987).

Helmut Newton was photography’s enfant terrible for years. In a career bolstered by scandal, Newton made headlines by putting saddles on naked women (1976) and S&M onto the pages of Vogue.

The large retrospective of Newton’s work at the illustrious Grand Palais in Paris bears testimony to how times – and tastes – have caught up. Co-curated by his widow June Newton, 83, the exhibition assembles over 200 works of a career that spun Newton’s lifetime, from 1960s fashion stories to celebrity portraits at the turn of the millennium.

Wandering through the gallery’s Art Nouveau rooms, it is hard not to be struck by the prophetic quality of Newton’s photographs. Whether it’s a bondaged model brandishing a fist or a saphire-clad hand grabbing a chicken crotch – whole chunks of the show remind me of today’s fashionably sexualized shoots by Steven Klein, Terry Richardson or Jürgen Teller. A 1976 story for the Pentax calendar includes an image of a naked woman floating in a pool with a battleship replica between her thighs. Other racy examples from the early 1980s include suited women surrounded by oiled-up beefcake men à la Schwarzenegger, or models posing nude in the street. These 30 year-old images were revolutionary at the time, now they feel curiously inoffensive. Has so-called bad taste become the norm, and is this evolution courtesy of Mr. Newton?

Newton’s background was marked by instability. Born Helmut Neustädter into a bourgeois Jewish family in 1920s Berlin, he fled the Nazi persecution at 18 and lived a playboy life in Singapore before ending up in the back of beyond, Australia. He set up a photo studio in Melbourne and changed his name to Newton, but restlessness and ambition drew him back to Europe in the late 1950s where his star rose quickly following work with British and French Vogue. His long international career was cut short by a car accident in 2004.

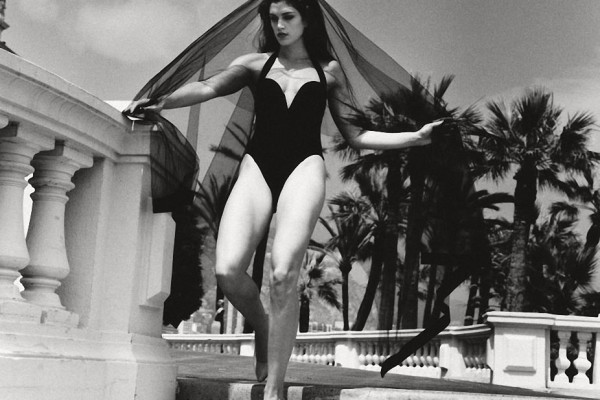

In a makeshift booth at the Grand Palais, a documentary on loop shows Newton as a graying gentleman in shorts and Hawaiian shirts, napping, then chatting charmingly with tourists and top models alike. In a scene from the early 90s, Newton directs a teenage Cindy Crawford to walk down a marble stairway in a bathing suit. Crawford’s muscular thighs shake with each Amazonian step, and the camera zooms onto her flesh. The photographer’s keyed up voice bellows “Yes Cindy! Cindy – again!” In many ways this scene epitomises Newton’s world – one of busty superwomen, objectified and unattainable (“essentially glaciers with breasts”, according to the New Yorker) but also revered and powerful. Heroine chic before the “e” got chopped off.

Another example? Take Newton’s arguably most famous series, Sie Kommen (1981). Displayed in the exhibition’s central room, it consists of two life-size images of a group of young women marching towards the viewer – dressed in chic attire in the first image, fully naked and equally aloof in the second. The title, “they are coming” in German, may be a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Allied army’s advance during WWII, but it also testifies to Newton’s prodigious fixation on the clout of female sexuality.

A quote on the gallery wall suggests Newton as a savvy predator. “I never intended my work to be in a museum. I’m a gun for hire.” The phallic connotation of the “gun” is no accident – the revelation in Newton’s 2003 autobiography that he had worked as a gigolo in Singapore testifies to his early appreciation of sex as a source of income. Perhaps this is why, above all, his daring vocabulary remains so widely imitated.

And yet, to me the most exciting part of this show makes us think beyond Newton’s reputation, to the deeper intelligence glimpsed on the edge of his oeuvre. It feels like a revelation to discover his more conceptual work in the last room of the gallery, such as a stunningly serene shot of a member of Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater being swallowed by a crocodile (Crocodile eating Ballerina, 1983). Another surprise is Main et dollars (Monaco, 1986), a close-up of a fleshy hand clutching a bunch of hundred dollar notes. Reminiscent of Martin Parr’s Parrworld series, this shot sheds an unflattering light onto the wealth underpinning the entertainment industry, and shows Newton’s rarely seen talent as a social satirist.

I walked away from this show wishing Newton had produced more of this subtle, self-aware work. Even if we will always remember him as Herr provocateur.