Mami woke up and found you sleeping with one leg dangling from the side of your bed. She moved closer and saw your eyes were wide open, one pupil shaking, the other immobile, your tongue slowly tapping the back teeth of a mouth that belonged to you no more.

¿Mamá?

¿Maruja?

¿Mamá?

Meanwhile, miles away from you, my best friend and I swallowed our second bottle of homemade sangria in my parent’s living room where my black cat—meowing and purring to the rhythm of her scurries—ran under my feet leaving behind enough wind in her shadow to sweep me off my drunken pigeon toes.

I tripped and spilled my glass of red sangria across the white living room wall.

Meanwhile, Mami rushed you to the hospital where you fell asleep and did not wake up.

¿Abuela?

¿Maruja?

¿Abuelita?

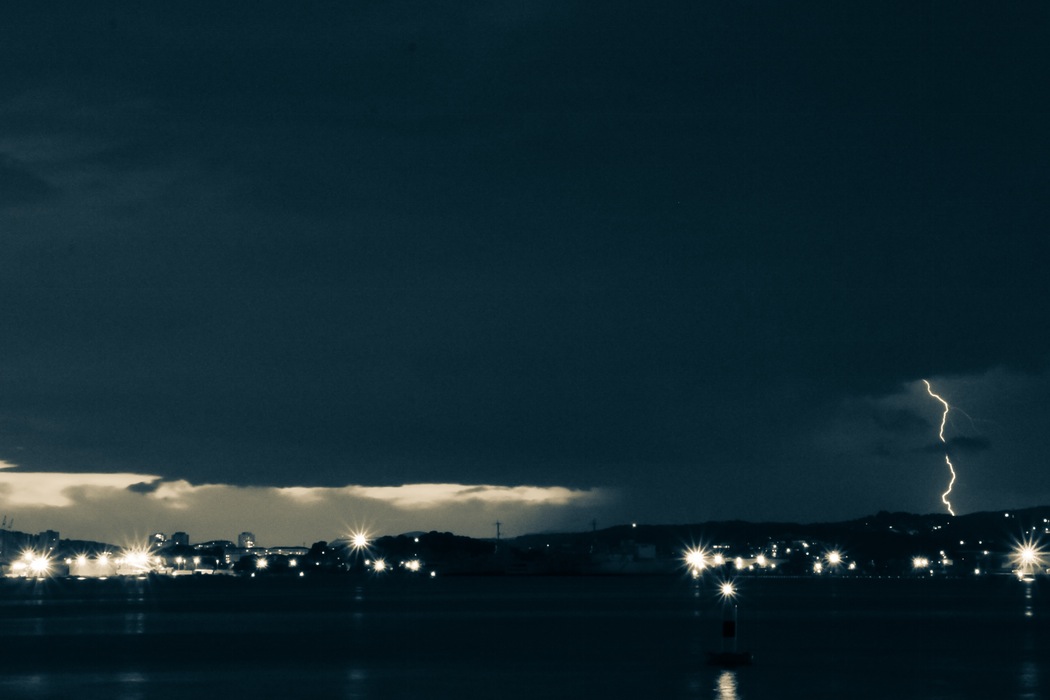

Since then, I hear your breaths hollowing to the rhythm of gravity pulling a wine glass to the floor, your last breath a streak of red wine on your daughter’s white wall.

Red wine and cats were two of your favorite things.

Mami told me you drank Merlot, she told me you recited “Oda al Gato,” your favorite Pablo Neruda poem, by heart at the dinner table, glassful in hand, hours before she found you between life and death in bed.

I can still hear your voice reciting el gato, el gato, el gato,

El gato,

sólo el gato

apareció completo

y orgulloso:

nació completamente terminado,

camina solo y sabe lo que quiere.

The cat,

only the cat

appeared complete and proud:

it was born completely finished,

walking alone and knowing what it wanted.

I had adopted a black cat because I thought your spirit would need a place to stay. I adopted her months before, when you weren’t sick, just old. After the last five years of your life— 85, 84, 83, 82, 81, —when I first saw death stretching its hands over your face, heard its spiny roots taking shelter on the insides of your ankles.

I thought I knew when I had seen you last.

I thought I knew when I would see you last when I heard a squeak and it was not your grandmother’s chair beneath you but your bones. Your femurs, like the wooden legs of that old chair, began to wobble more in their places, rasping against their joints, louder and louder, the loudest when you spoke to God.

As time passed your legs spoke to him more, they’d meet him on your balcony where they paced back and forth and you called for your Father,

Padre Nuestro que estás en el Cielo,

Santificado sea tu nombre,

venga a nosotros tu Reino.

Hágase tu voluntad

así en la Tierra como en el Cielo.

Abuelita, you did not believe in heaven for more than 70 of your years on earth but hallowed be thy name, María.

Hallowed be la virgen María, you’d say, so why did you not like to be called María?

Call me Maruja, you’d say, and you only had to live up to the expectations of a woman with domestic propriety. You named one of your cats María Magdalena, though, and she was one of our favorites. And although you, Abuelita María, had abandoned your holy name, thank the lord you never lived up to the meaning of your nickname. So hallowed be thine two names, too, Maruja and María Magdalena.

María Magdalena had different colored eyes, one blue and one golden, she stood on top of your small European refrigerator in between two lit candles at night. She always knew what she wanted and whom she was looking out for. She held herself up securely and with the sweetness and simplicity of her curved mouth, she would make you feel like something was not quite right with the air. Something thick like honey would drip in the air of your kitchen. Honey so thick that when you took pictures the corners of your photographs caved in.

That’s what María Magdalena was good for, you said.

Tunnel vision, you said, a reminder of the scarlet middle-name permanently adulterating Jesus Christ’ mother, María.

I never asked, so I’ll never know, but did you name your favorite cat after a prostitute? Did you want Magdalena to remind you of the sore sins sinking deeper and deeper into your shoulders?

Guilt, you said. That’s what María Magdalena was good for.

Thou hath coveted, thou hath bore false witness, or so thou thought, María Abuelita.

And so in the company of your cats you would give up TV when you lied to one of your children, you would give up bread after a night of wine and pray the Rosary. You would stick your tongue out at me while reciting Ave María,

———tongue out y Dios te salve, María, llena eres de gracia,

———tongue out y bendita tú eres entre todas las mujeres,

——-tongue out and Rejoice, Mary full of grace,

——–tongue out and Blessed art thou amongst women,

You’d stick your tongue out my direction in between verses and laugh. I’d hear the familiar sound of your noisy gas in between your thoughtful snores and laugh. I’d wait to see the ebb and flow of your long and winding chest wrinkles just to make sure you were still breathing, and catch your lips smeared in wine-lipstick, surrounded by grey whiskers full of sneaky breadcrumbs.

Who were you hiding bread from, María?

Danos hoy el pan de cada día.

Perdona nuestras ofensas

como nosotros perdonamos a los que nos ofenden.

No nos dejes caer en la tentación

y líbranos del mal, amen.

Give us this day our daily bread,

and forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us;

and lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil. Amen.

It was strange to walk into your room when you yourself hadn’t been there in months. Everything was exactly as you left it, your smell smeared all over the walls, tattered curtains, dusty tablecloths and wool sweaters. The smell of a vanilla field with a baby’s diaper—that noisy gas and those sneaky saltine crumbs.

Mami and I flew to your house in Cali, Colombia to find the right thing to do with your things, your had been’s, had not’s, would be’s, wish knot’s were sprawled out in many rooms, like this: Books so dusty you could draw

on their covers with your fingers, Rolled-up wrinkly brown posters of classic

Monets, Renoirs and Van Goghs— from the ballerinas to rolling hills of paint like swirling windmills—

your vanity diced in twelve boxes, in blue bags

made beige with concealer and reddened, pinked, oranged, purpled

with a lipstick for every outfit, for every occasion.

Silver platters, silver spoons, silver cups, the first one Mami ever drank from, your second and last anniversary present

a dried rose you kept from your mother, from when she used to sell flowers for 10 pesitos and you and her

and your 4 siblings slept in a single room.

And cats, tus gatos, completos y orgullosos,

21 gatos spread out and wailing,

some waiting, some mourning.

3 on your bed, 3 on your windowsills, 2 on your velvet chairs

2 on your vanity, 2 at the end of your bed,

2 on your pillows, 3 under your bed,

3 in your shoe closet where mama cats had had their babies

for more than 1,2…85 years,

Espectáculo, Bonito, Siam, Micha, Micho, Purrunga, Mirringo, Macho, Macha, Pecha, Pillin, Peky, Lindo, Mágico, Tonto, Terco, Adorado, Idolatro, Mecato, Mirringo, were all caught, put into carriers, and shipped to shelters or adopted homes; every single one of them except 1, the one nobody knew disappeared when you left, and only came back when you returned.

María Magdalena had not been seen for months even though your landlords kept finding balls of her grey and white fur on top of your refrigerator where, during your absence, she had tried to guard your kingdom. Nobody except the cats had been allowed to touch your things, until news travelled south from the Caribbean announcing the queen’s unexpected death. Your room then became a war zone where all, except one, were taken away by force to be shipped, imprisoned, or sold.

I imagine this is how María Magdalena experienced your disappearance.

She was the sole survivor of the apocalypse brought to life by your death.

María Magdalena had remained in hiding until the moment Mami and I tried to enter your room, and within seconds, María Magdalena rose from underneath your bed and blocked us from stepping deeper into your room; her wiry, grey and white fur shaking, growing taller from her mountainous spine and cactus-like tail. Her blue eye locked itself on my gaze; her golden eye bounced like a tennis ball ↓.

. from Mami’s face →. to my eyes ↓.

↓. entered we door the to.← eyes my from

from the door we entered→ .to the open windows ↓.

↓. sills moldy their to.← windows open the from

from their moldy sills→ .. to crummy bowls of cat food .

Abuelita, you know I’ve never believed in God or in souls leaving the departed, shooting out from the top of their human’s head in billowy clouds of smoke or purplish-blue air. But Abuelita, more than once, I’ve looked deep into an animal’s eyes and seen such entanglements of self-awareness and judgment only complicated enough to be human.

A cat’s eye can be aware of time.

Abuelita, María Magdalena and I were locked in each other’s gazes long enough that her eyes became yours. I hoped you or she would see something in my eyes, I desperately wished to break the boundaries of our skins and furs,

¿Estas ahí?Are you there?

¿Estas bien?Are you okay?

¿Tienes miedo?Are you afraid?

¿Qué te hace falta?What are you missing?

¿Dejaste a alguien atrás?Did you leave someone behind?

That time was passing was my only thought left.

You and María Magdalena bid me farewell. Then the two of you scurried under my feet and out of your room with a burble and a shadow of wind much too similar to the one my black cat had blown on my feet that night I dropped the glass full of wine staining my mother’s, your daughter’s, white wall with red.

Where do you remain, Abuelita?

I relived your lingerings. I saw silhouettes of your movements and gestures, heard the echoing of the quietest sigh you released on your last day in this room. I retraced the surfaces your hands had swept or sweated, searched for lone head-hairs or whiskers lodged between the threads of your bed sheets. I searched for the squeaks of your bones hanging still and steady in the air, felt the resonating crack of your wrist on the doorknob you last turned, walked barefoot on top of the curled carpet fibers that had last cushioned your feet shuffling from your kitchenette to your bedside where you had moved your 40-year-old scale to weigh your last oversized suitcase to America.

Where have you gone, Abuelita?

I talked with you every night for a year.

I liked carrying pieces of you in one of your pinky rings or worn bronze bracelets or black purses with spots of beige concealer. But your insistent balcony talks with God and your passionate fight for a space in heaven made it impossible not to wonder whether you had gotten what you wanted.

I wish you a spot in the heaven of your truth,

Even if in my truth there is no heaven,

Amen?

Are you on earth or in heaven?

¿Abuelita, Estás en la tierra o en el cielo?

My black cat must have gotten annoyed with the monological chatter taking over my sleep because one night she changed our nightly routine and stopped curling on the tops of my feet to snore.

Where have you gone, black cat?

The first night I found you sleeping on the bed of the TV room, I picked you up and placed you in the nest of pink wool scarves you had spent more than a year kneading at the foot of my bed. The second night I found you in that same room but you were wide-awake and sitting up on a tall chair with your gaze stuck on the ceiling. The third night I slept in the TV room with you where I could feel you sleeping soundly on the tops of my feet until I woke up to the glare of your yellow eyes, darting like two mini headlights from the TV to the fan to the night lamp, from the fan to the night lamp to the TV, and then resting them on the most clandestine edge of the ceiling. You did this every day, sometimes multiple times, and many times I’d mimic the movement of your eyes darting around and across the room hoping that with enough practice I could see what you were seeing.

A clear image never came with practice, but after weeks of your yellow eyes beaming on that dark corner I deciphered an outline on top of bubbled white wall paint.

What are you doing on the ceiling, Abuelita?

¿Estás bien?

For months now you have roamed to and from the TV-room and my bedroom. You are not sad or happy, just caught on glimpses of life, fading, skating, existing with all your chromosomes and then unexisting too. Dying a little more. You continue to enjoy the in-between of rooms and me seeing and not seeing you ever again all the same.

You scurry in and out of the closets, the bathroom, the office, the living room, bounce down the stairs and outside, up the mountains, closer to the roof where you pounce on the windowsill to eat the kibble and water that’s still left outside. You are as stubborn as you once were, convinced no one loves you after your fifth glass of wine, convinced María Magdalena watches over you and counts your sins, that all will one day be forgiven and forgotten.

El gato,

sólo el gato,

nació completamente terminado.

—

Originally from Cali, Colombia, Verónica Jordán-Sardi immigrated to the United States as a young teen fleeing severe sociopolitical unrest. She holds a B.A. in English Literature and French from the University of Florida and an M.A. in Comparative Literature from the University of Iowa. Verónica is currently a Diversity Scholar and M.F.A. candidate in cross-genre writing at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, California.