Review by Meghan Flaherty

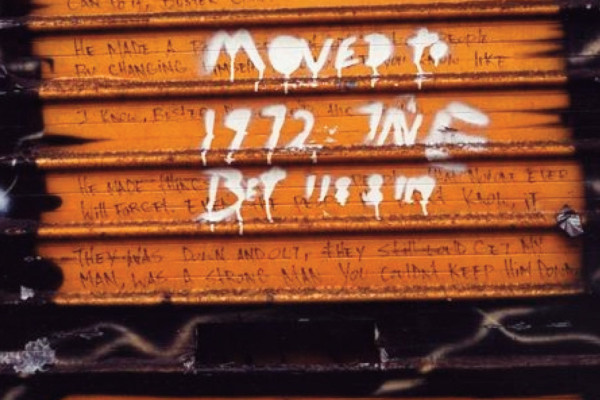

In Harlem, distinguished professor Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak attempts to create a poetics of academic idiom. It is a handsomely illustrated hardback volume no bigger than a Kindle. The matte cover shows off two of her collaborator Alice Attie’s photos, in vivid urban hues. Spivak, to use one of her verbs, ‘locates’ Harlem as the site in which “African-American” as a concept remains under negotiation. She presents sixteen photos of that robust, resistant neighborhood now more than ever on the brink of gentrification and possible decay. The photographs contain no figures. They focus instead on what she calls “inscriptions”: text that, by accident or design, stands between the twin engines of ruin and development. The “space” created by the book aligns neatly with the idea of the “vanishing present,” one of the foremost subjects in her work.

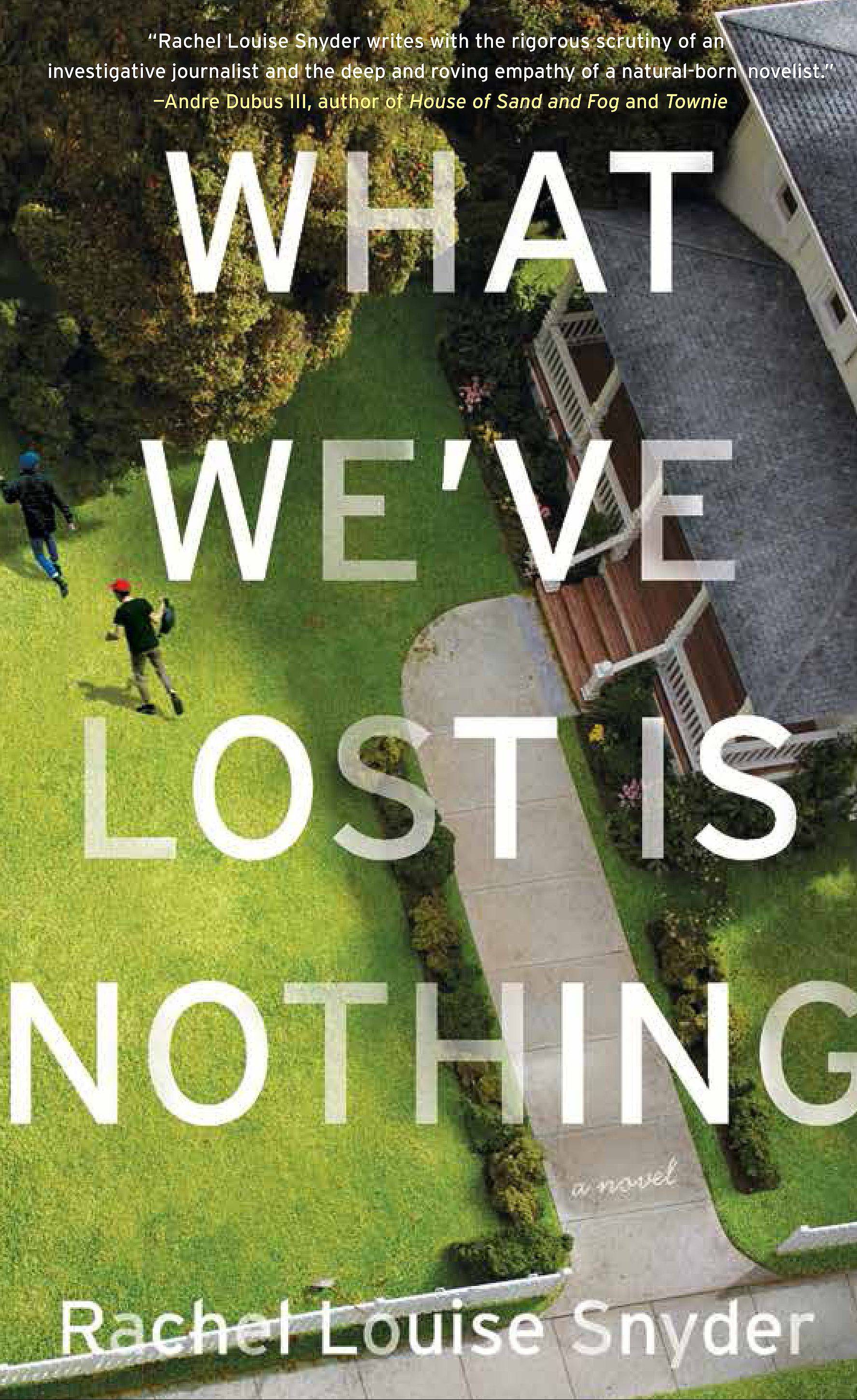

As a philosopher and critical theorist of distinction, Spivak is best known for challenging the legacy of colonialism, and for examining the identity of the subaltern – used in this context to describe the person or group of people socially, politically, and geographically outside the hegemonic power structure (see her 1995 essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?”). Here, she centers on Harlem, arguing that “no amount of pious diversity talk will bridge the constant subalternization that manages the crisis of upward class mobility masquerading as the politics of classlessness.” In conversation with Du Bois, Gramsci, Kant, and Yeats, Spivak threads her questions about the changing cultural landscape of Harlem through her larger discussion of the changing cultural landscape of the globe – Harlem’s place, her place, Calcutta’s place, a New Yorker’s place, our place, their place, women’s place, and most urgently the subaltern’s place therein. She concerns herself with culture, with identity in megacities, and with “collectivities.” Her essay appears to posit several questions, most of which remain unanswered:

“What is it to be a New Yorker?”

“As ‘culture’ runs on, how to we catch its vanishing track, its trace?”

“In the face of class-divided racial diversity, who fetishizes culture and community?”

What does it mean to ‘memorialize’? If these inscriptions are messages, who sends and who receives?

The inscriptions themselves consist of graffiti, hand-written signage, official interdictions, murals, storefront advertising, words reflected in a window, and tags on merchandise. The identities of the message-leavers and the intended recipients remain a mystery. Harlem is merely trying to provide a record. To catalogue certain of these bits of text as emblematic of a neighborhood perilously in flux. To mark the “moment of change.” It does not pretend to be empirical; Spivak disavows “archivization” in favor of a more imaginative approach. She and Attie “resolutely kept to rumours,” comparing their project to “poorly edited oral history,” and all the “boring authenticity” that goes along with that. The photos and text presented here make no claims to objectivity. This is precisely the idea – and what is so interesting about her work. It is history from the subaltern’s point of view, subjective, scrawled wherever possible among the artifacts and records of the dominant, colonializing class.

The sites photographed become case studies of development. A spray-painted message, “WAKE UP BLACK MAN,” shot through a chain-link fence, is replaced with an apartment building and a bourgey children’s gym. Corvette, once a flagship business in Harlem, is replaced with a Duane Reade. She describes the entire argument of her essay (in neat parentheses, no less) as “the fragility of the differantiating moment.” Differantiating does not mean differentiating. The term refers to Derrida’s concept of différance, coined in his 1967 de la Grammatologie, which Spivak translated in 1976 and again in 1997. You will not find ‘differantiating’ in the dictionary. And here is where the little volume may lose the reader.

Harlem, essay/art book/article, attempts to give us both a work of scholarship and an aesthetic object, and it really only fails at the latter. First, the visual elements don’t quite cohere. Spivak’s professorial enslavement to the visual aid allows other, more incongruous images to get through: archival photographs, digital enhancements, loosely relevant bits of illustration, which detract from the overall consistency of her argument-in-pictures. Perhaps this is an example of content influencing form—or lack of possible form given the content. Perhaps this was intentional.

Secondly, prose-wise, Spivak is an acquired taste. Without casting the slightest aspersion on her significant scholarly contributions, nor meaning to throw down another sister in the already unfair fight of published letters – the critical equivalent of a girl foul – I must warn the would-be reader that Harlem, at barely seventy pages, is a demanding read.

In our age of frankness and approachability in prose style, we often look to Orwell – and for good reason. Spivak, I regret to say, commits each of his cardinal sins: imprecision, staleness of imagery, verbal false limbs (set down by, coming forth to code), pretentious diction (globalized contemporaneity, allochthonic), dying metaphors (the gutted warehouse), and meaningless words (originary hybridity?). She overuses ‘stage’ and ‘locate,’ both as verbs. And she breaks Rule #5 repeatedly: “Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.” Her prose feels both dead and bafflingly, teeth-baringly postmodern all at once, as if she set out to create new words from older, bloodless ones to infuse them with new meaning. This she may have done. I admit to lacking the deconstructivist vocabulary necessary to fully parse her essay. And there’s the rub. Who is she writing this to and for? If she wants to reach anyone outside her wing of the academy, I’m not sure she succeeds. Even the most intrepid looker-upper stumbles here.

Then again, who was Orwell if not a member of the colonizing class? A white and wealthy man, stepping, dignified, into the canon with his quill held high. His principles of language, however pleasing to us, are still just one patriarchal point of view. If Spivak wants to wield her language how she pleases, she is well within her rights. My only question is: will she alienate her reader? Might there have been another way to phrase “abyssal specular deterity,” perhaps? A way to show us what she means? Though Spivak does meet each of Orwell’s four great motives for writing prose: sheer egoism, aesthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse, and political purpose. He wrote in “Why I Write,” that attempting to separate politics from art “is itself a political attitude.” Spivak has fused the two together in this form: critical theory as art object, essay as ethnography, bibliographical collage.

With Attie’s sixteen photographs, Harlem provides a visual testimony to “anonymous unclaimable delexicalized collectivities” free from the “humanism of human faces.” This is important work. I now have a better idea, for example, of what ‘teleopoesis’ means, which is to say: “to touch a past that is historically not ‘one’s own.’” We want to imagine ourselves into the ‘other,’ and we sometimes use the binaries of ‘us’ and ‘them’ to blur the lines between them. This is the work of the imagination and, from a literary perspective, this is what we do as readers and as writers. This is the pursuit of empathy. When empathy is not enough, Spivak asks us what becomes endangered by development and multiculturalism. More baldly put, “What are the implications of corporate promotion of culture as a tax shelter in today’s Harlem?”

Terry Eagleton, for all he also criticized her prose style, has written that Spivak “has probably done more long-term political good in pioneering feminist and post-colonial studies within global academia than almost any of her theoretical colleagues.” Judith Butler came even more forcefully to her defense, lambasting Eagleton in the process, when she said, “The wide-ranging audience for Spivak’s work proves that spoon-feeding is less appreciated than forms of activist thinking and writing that challenge us to think the world more radically. Indeed, the difficulty of her work is fresh air when read against the truisms which, now fully commodified as ‘radical theory’, pass as critical thinking.”

To think the world more radically. That’s just the kind of construction we could find difficult to parse – certainly the eye stalls; we blink to make sure we’ve read correctly – but it is not. To think the world. This works. The preposition is omitted, ‘think’ becomes a more fiercely active verb, and ‘radically’ modifies the thinking process, rather than the necessary adjective we imagine will come next. No further explanation is offered, but none is necessary. It’s just a different kind of language use. Butler also wrote that cloudy style, by questioning language’s grip on reality, “can help point the way to a more socially just world.” No doubt Spivak aims at this. She leaves us with the swelling crescendo of a plea to our imagination, to try and touch the distant other, to “honour what we cannot ever grasp.” She strikes her augmented seventh at the end. But could she have foregone, along the way, a bit of her opacity to open up the hardbound covers of her fiery little book to those who wouldn’t otherwise have the definition of différance at their fingertips? In future works, I hope she finds some happy middle ground between her fearless coinages and spoon-fed clarity. For now, we’re left to squint sideways at the jargon and hope we can make sense of it.

Meghan Flaherty is an MFA candidate in creative nonfiction and literary translation at Columbia University. You can find more from her at meghanbeanflaherty.wordpress.com. She lives in Bushwick with philosophers.