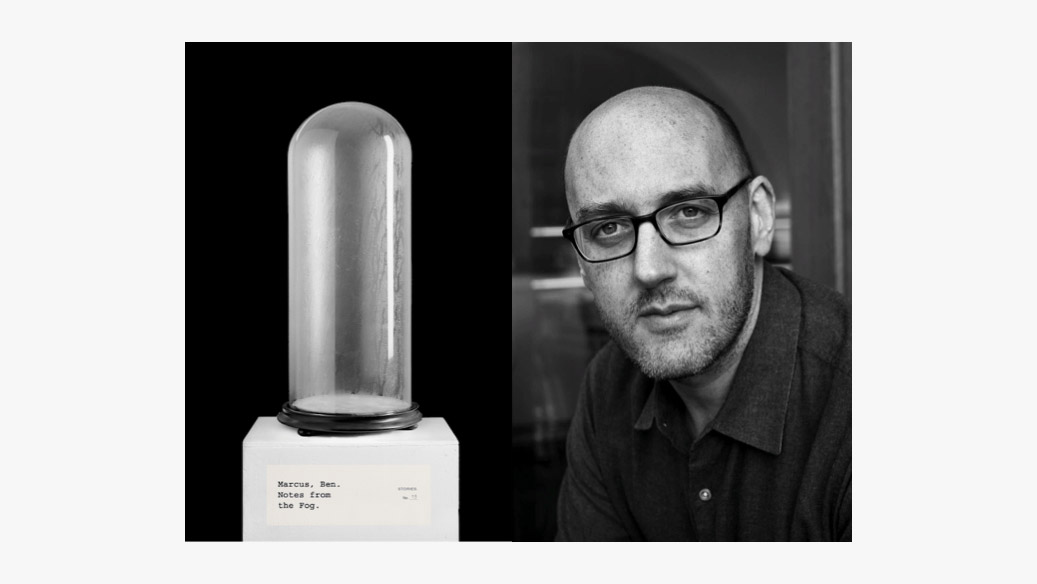

In this interview with Columbia Journal’s Online Fiction Editor Liz von Klemperer, Ben Marcus talks about sequencing his stories, writing characters that want the unattainable, and mood-enhancing mist, among other things. Marcus is the author of The Flame Alphabet, Leaving the Sea, Notable American Women, and The Age of Wire and String. His latest collection, Notes From the Fog, was published by Alfred A. Knopf on August 21st.

I’m interested in your treatment of architecture and physical spaces in these stories. In both “Blueprints for St. Lewis” and “Critique,” design is used to manipulate emotion. It is used to induce grief and even warps the perception of time. How does the architecture you are surrounded by influence your writing, your perception, your emotional states?

Understanding one’s own influences presumes a degree of self-awareness that is just colossal, and frankly that I would not want. But there are rooms that undeniably make me happy, along with spaces that crush the life out of me. I’m interested in the ideologies behind architecture, the way buildings are pitched to communities as objects that might rectify some kind of deeper disorder. Buildings house people, but maybe they also solve other problems, or create new ones. And there’s a desperate language around what a building might do for a person or place. There’s quite a bit of overpromising, as if a building might change us. The mood-enhancing mist in “Blueprints for St. Louis” seemed like a kind of natural evolution for architecture – just making the mood manipulation more explicit, more assured. I wouldn’t mind a mood-enhancing mist to steam off of a book I wrote. In “Critique” I was interested in talking explicitly about the made world as we might about a work of art. To subject the world itself to the kind of critique we might use for a piece of writing or a painting.

You discussed the story “Stay Down and Take It” in a recent New Yorker interview with Deborah Treisman, and you said, “technology causes sorrow. Sorrow leads to desperate acts that only deepen the sorrow. There’s a math equation for that, I think.” Could you expand on the nature of this equation? Particularly in relation to stories like “The Grow Light Blues” and “Prophecy” where technology features prominently?

In retrospect I think that I am often trying to build an engine of calamity, and technology—its promise and its ultimate hollowness—is always ready at hand. We can have ridiculously high expectations for it, and this is a strong dramatic situation, for me anyway (hoping and angling for something that almost certainly will not come to pass). Characters wanting something unattainable, longing to be other than themselves. Some technology implicitly traffics in promises of these kind of leaps into better, happier identities. And I guess there’s a creepiness and unease to all of it as well.

You say in the same interview that strict realism gives you feel a “queasy vulnerability,” but that you occasionally “test the waters of unassisted reality” anyway. What drives you out of the comfort zone? What can be gained from confronting this kind of queasiness?

Some of this is just connected to my early value system as a writer—the things I was attracted to, the things that bored me, the things that propelled me. But eventually I just became tired of my own positions and ideas. They weren’t leading to work that I cared about very much, so I had to adjust my approach and deliberately try things that I thought I had ruled out. Like any writer, I suppose, I have certain tendencies and crutches, little things I do to amplify what I’m writing, and many of these are slightly untethered from a strictly realist space, or else they flirt with something vague and mysterious. So now and then I will try not to allow these devices for myself, just to see what results. I guess it’s a kind of constraint.

“Notes From the Fog” is set in a relatively unassisted reality. Did writing it make you feel queasy? Can you speak to the decision to make this your title story?

I had a different working title for a while, but when I saw it on early cover designs I lost interest in it, and then Notes from the Fog just seemed to capture the book better. I don’t think I felt queasy about it. In an earlier draft of the story I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, so there was a lot of placeholder otherworldly stuff, just posturing in the middle of the story with no purpose. But the narrator’s voice finally took hold for me, and I found that there was more power and tension in the quotidian in this story, so I tried to strip away the distractions.

Can you speak to the sequencing of this book? How did you arrange these stories?

I kept changing the order of the stories well into copyediting. I’m not really sure how I do it. Some stories are thematically pretty close to each other, so I kept them apart. Others had overlapping techniques, so I separated them as well. In the end it’s about how it reads in certain orders, and how to carry a reader through an experience. But I myself don’t always read story collections in order, so I am skeptical, in the end, of how much I can control just by determining the order of the stories.

Your stories depict humans as self-absorbed “need machines,” doomed to alienation and Boredom. “Notes From the Fog” ends with the sentence “something amazing is coming,” a surprisingly hopeful sentiment, particularly for the last story in the collection. Can you speak to the ability to expect the amazing, despite the chronic monotony and dissatisfaction that marks human existence?

I see the ending as pretty grim. I thought that line was ironic. He is talking about a tree that might come down and crush them all, and so he makes his children sit under it with him, increasing their risk. So that amazing thing that is coming might just be what obliterates them. But I guess I don’t mind if it looks like a hopeful line instead.