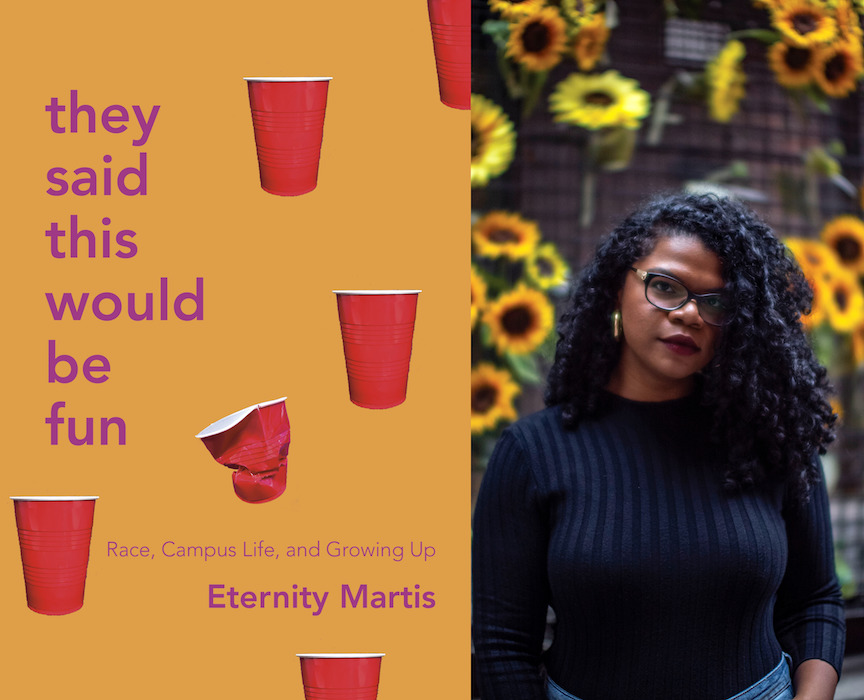

Shalvi J Shah, an MFA candidate in Fiction and Literary Translation and Teaching Fellow at Columbia University, talks to author Jenny Bhatt about craft, cultural stereotypes, her debut short story collection Each of Us Killers, and how far artists go to create.

Jenny Bhatt is a writer, literary translator, and book reviewer. She is the host of the Desi Books podcast. Her debut story collection, Each of Us Killers: Stories, came out with 7.13 Books in September 2020. Her literary translation, Ratno Dholi: Dhumketu’s Best Short Stories, came out in October 2020 with HarperCollins India. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in various venues in the US, UK, and India, including The Atlantic, NPR, BBC Culture, The Washington Post, Literary Hub, Longreads, Poets & Writers, The Millions, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Kenyon Review, PopMatters, Scroll.in, and more. Her fiction has been nominated for Pushcart Prizes and the 2017 Best American Short Stories. She was a finalist for the 2017 Best of the Net Anthology. Having lived and worked her way around India, England, Germany, Scotland, and various parts of the US, she now lives in a suburb of Dallas, Texas.

Place is an important commodity to many of the characters in EOUK. Some of your writing is imbued with the texture of its real estate, and some of it relies on memory, spirituality, work-life, and oral narratives. How important is both physical space and microcosm to you when it comes to writing?

Yes, several of the stories have place as an explicit theme. The space or place in a story is metaphorical or physical, as you rightly observed. In some stories, a character is negotiating their place within their work community. In others, they’re navigating the challenges within their workspaces. I was exploring the causes and effects of such constant work-related negotiation and navigation and what that means for their personal lives. We’re never going to be able to get rid of the power imbalances in our workspaces and places because the forces that create such imbalances—class, gender, caste, ethnicity, job role, race, nationality—intersect in complex, deeply-layered ways. And we’re all conditioned from an early age as to how we respond to such imbalances. The best a writer can do, I think, is peel back the layers a bit to help us become more aware of these forces and how we deal with them. The best I can hope for, with this collection, is to help a reader question their own prejudices and biases as they read.

“The Prize,” a story in the latter half of the collection, is about real estate and corruption in an Indian city but skews the spotlight, in the end, on women and marital life. What inspired its subversions? And how did you move through the writing of it?

When I moved to Ahmedabad in 2014, I experienced a lot of stuff around homeownership—bureaucracy, paperwork, “money-under-the-table”, never-ending stages of the process. Many people, including my family, talk of this as a normal cost of doing business. And I kept thinking, yes, but there has to be that first moment for each of us when we decide: I’m going to accept this as a way of doing business. I wondered about the effect of that singular moment. For me it was agonizing, and I’m not like Mother Teresa. I would argue with my dad how it’s not about the amount of money, it’s about the principle. I wanted to understand why it bothered me so much more than it seemed to affect some others.

But yes, you’re right, you can’t just write a story about one thing, right? When you talk about something fundamental changing within a human being, it changes not just who they are to themselves, but also who they are with the people around them. I wanted to write about that, too, but without playing into stereotypes. So I start with this posh Italian restaurant because that’s also an aspect of this complex, layered city. We know about the slums. We know about the Muslim ghettos. We’ve also got the Rajasthani migrant workers. I wanted to show different aspects of the city that I was living in while exploring what this “cost of doing business” does to a person and their personal relationships.

It’s almost as if it’s not even about corruption. It’s about power dynamics because everyone’s trying to move through that class divide.

Corruption, to me, is about people exerting their positional power unjustly onto others. So, yes, the story is about the dynamics of power on three levels—you see it at the class and caste level in how the two men, Nikhil and Manoj, interact with each other and how the migrant restaurant manager is treated. And then there’s the gender dynamics. I remember when the story was first published and a Facebook friend commented, “Oh, Megha and Ekta, they’re just trophy wives.” I said, “Did you read it? The women made the whole thing happen.” I wanted to upturn some of those patriarchal gender dynamics. The women aren’t just quietly suffering in the background; they’re making things happen.

As you mentioned, women and minorities are often subjugated in writing. It’s widely discussed in not just “The Prize” but also “Time and Opportunity.” It shows a whole other side of the religious dynamic where the narrative observes how everyone regardless of their beliefs is suffering. The only person who is not being oppressed is the person who grabs power by any means possible. It is noticeable however that the dosa stall owner is Muslim, and the one who works for him is Satish, a lower caste Hindu. While religion doesn’t really play a role in this story, you’ve subverted the power dynamics of that equation as well.

I didn’t want to show the usual, simplistic view of the oppressed Muslim minority. In India, there are more complexities and layers because of caste, class, and gender. I wanted to show—with sympathy, I hope—what was motivating each character. But I didn’t want to play to the stereotype of the bad Muslim or the oppressed Muslim or the religious fundamentalist Muslim. It’s about exploring how the intersecting caste, class, religion hierarchies affect each character. Some South Asian books published in the West oversimplify the Hindu versus Muslim issue. As you know, class and caste go across the religion barrier. There are caste hierarchies in Islam as well.

This fear that the protagonist of “Time and Opportunity” has is also about losing his place in society. It’s not just related to whether he’s going to face any punitive measures by the government. He’s worried about himself and what his station is in the minds of everyone he respects.

I wanted to write about a street vendor because I grew up interacting with them daily in Mumbai. We knew certain vendors as if they were family friends and we only bought our Bombay sandwiches or our chaats from them. In my research for the story, I found these academic studies done by students at Indian universities. Mostly, they were about recommendations to the government to improve working conditions related to, for example, hygiene issues by providing more mobile toilets. They all also wrote words to the effect that “. . . street-vending is a fact of life in India, you’re not going to get rid of it. But here are things we can do to improve their lot.” One of the studies was mostly a summation of interviews with Mumbai street vendors. Some of the conclusions were about how attached they were to their little bit of real estate, that three-by-two stall that they had worked so hard to get after migrating to the city from some small village or town. That stayed with me. And I wanted to explore these complex, intersecting dynamics of religion, class, and caste. Just like we talk about intersectional feminism, there’s intersectional casteism, which we really need to understand better.

Another EOUK story that is about making ends meet is “Mango Season.” It is heartbreaking; it is also very seductive. It’s not easy to create these complex and layered microcosms, where in one scene you use billboards as a way to capture that whole moment in time. Then you use a La La Land-esque dream sequence to give us a macrocosm of what’s going on in the protagonist’s head. How did you approach writing that?

I moved back to India mid-2014. This was right after Prime Minister Modi’s first win. Everywhere I went, I saw these huge billboards. It was fascinating because, when I left in ‘91, you didn’t see these massive ads in politics—so dramatized and so in your face 24/7. We didn’t even have social media. I was also seeing this myth forming around him, which is, as you know, this chaiwalla, this tea-seller who’s made it good. And he’s going to save everyone, he’s going to bring jobs and good days to everyone. At the same time, there was an ongoing, horrific spate of farmer suicides. I was meeting young Muslim men who were sharing how they had to live in the outskirts of the city because they’d been ghettoed since 2002; how they couldn’t live in the city like their parents used to; this Indian brand of gentrification meant they had these terribly long and draining daily commutes. Juxtaposing all that, there was this manufactured propaganda in 24/7 news media. I wanted to understand what it’s like if I’m a young, marginalized man with all these hopes and dreams of making it and working my way up from the bottom of the food chain—what hopes and dreams do I have? What’s igniting that fire in my belly?

Around then, from a craft perspective, I’d been reading various articles and essays about how South Asian writing panders to the white gaze by exoticizing. “You know, they put saris and mangoes and spices and the exotic descriptions.” And I thought, wait a minute. I do know some writing that does so in gratuitous ways. You, as a reader, know that it doesn’t have to be there. But what if it’s essential to the story? In India, saris are a big deal; my mother would spend hours in a sari shop before every major event or festival. And mangoes? I mean, we would have discussions about which mangoes were the best that season and which ones we should buy by the crate. It was vital to our summers.

There’s a whole conversation about what box of mangoes to order, who to send it to, what to make with it.

Exactly. My mother and her friends would exchange all these market secrets and recipes, “Buy this, don’t buy that, why don’t you make your own garam masala?” I still do it with my siblings. This is truly everyday life in India for hundreds of millions. So if you think it’s pandering to the white gaze, you haven’t been to India or you only know it as a tourist. I’ve read such accounts by certain diasporic writers who haven’t really spent time in India other than vacations, where they come back overwhelmed by all of it and want to write about it. I wanted to be subversive by writing a story that had all these tropes—mangoes, saris, spices, slums, Bollywood. It’s the one story where I threw in everything and the kitchen sink. But I wanted to make these timeworn tropes essential to the plot. They’re not just there. Rafi is an employee at a sari shop and lives in a slum area. Mangoes are what he remembers of his dead mother. There’s Bollywood music and spicy food in that dream sequence. It was an experiment for me to see if it can be done in a way that isn’t your usual caricatured or stereotyped script.

Trauma, place, and memory constitute the titular story, “Each of Us Killers.” This story cut me very deep. The collective trauma in it was hard and necessary to read. It must have been painful for you to write. I’ve always wondered how different writers, if their writing deals with trauma, handle the resulting hurt.

“Each of Us Killers” was based on the real-life Una floggings. I’d been watching it all unfold on the news, including the following riots. When I first started to write about it, it just wasn’t working. Although it wasn’t because I was traumatized. The writing wasn’t moving me and that means it wasn’t going to move the reader. Then I went to Diu for a weekend. Una wasn’t too far so we stopped to talk with some people. I positioned myself as a journalist because “writer” doesn’t cut it but “writing for newspaper X” does. They treated me well and answered my questions politely. But there was so much I felt they were deflecting or not speaking of. In the story, the community is hiding a secret. I don’t think that was happening in my real-life meeting but the way that conversation unfolded made my writer-ly imagination churn. It could be that they didn’t want to bare all of their wounds to a stranger. They were also all men and it could be that they preferred to be seen as capable of handling problems within their own community. It’s been like this for centuries, right?

Anyway, that was when something changed for me, because of having actually sat across from them. It gave me the human face to the whole tragedy. I couldn’t sleep after that. I kept recalling their stoic faces and voices. I could have just sat there in my nice cozy flat and taken everything from the internet or TV. It might have worked, I don’t know. But the energy and urgency on the page, for me, came from that encounter.

To your point, I had struggled with whether I was the right person to tell that story. I switched the point of view and narrative voice multiple times. I didn’t want to speak for all caste-divided villages everywhere or even any one oppressed, lower-caste individual. So I wrote with a collective voice for a specific, fictional community.

Please talk about the collective voice!

The people I talked to in Una were so united in how they were responding to me. There was something unusual in that whole conversation where it was me as a “journalist” versus a community (though not exactly against them). I wasn’t comfortable writing with the POV of the sarpanch or the shopkeeper or one of the villagers or the journalist. I didn’t feel comfortable representing any of them individually and speaking for them. So I represented them as a collective voice, as a community—which was my experience of them.

In “Journey to a Stepwell” I could feel that you may have been inspired by Gujarati writer Dhumketu, whom you’ve translated. Were there any folklore myths or oral narratives that you followed as you wrote it?

Not Dhumketu because he didn’t do folklore. He did social realism and history. Jhaverchand Meghani, who I’m currently translating, was definitely one inspiration. The direct influence, though, was my mother. The folktale is about four sisters and we’re four sisters in my family. My mom’s version of the story had a moral or lesson for the four sisters about behaving as they were told if they wanted to secure good husbands. It’s funny because she would change some details with each retelling, depending on the particular lesson she wanted us to take away at the time. As most parents do, right? I would argue with her every time she changed parts of the story. She’d say, “Go write your own story then.” So I wrote this feminist retelling where the four sisters have skills and layers of their own and aren’t just living to get married.

What’s your favorite space or location to write? What’s a comfortable environment for you to build that writer-ly momentum?

That’s an interesting question because I’ve moved around so much geographically throughout my life. When I moved back to the US in February, for the first two months, I wasn’t writing nearly as much as before. I did 8-10 hours a day when I was in Ahmedabad. I lived alone in a flat with no distractions and, if I wanted to just shut the world out, that was fine. Here, I got married and the pandemic started. It was chaotic initially. Now we’ve gotten to a rhythm where I’ve got my physical desk space. But, more than that physical space—which does matter, of course—it’s about headspace. The approach I’ve taken is that my journal is my trash basket. If I’ve got a lot of things going on in my head, I’ll write it all out there. Then it’s in a different holding place and I can focus on some real writing. That said, a compulsive, habitual writing practice is a real privilege and I’ve worked hard to earn it. I never take it for granted.

Photo Credit: Praveen Ahuja