by Elisabeth Sherman

—

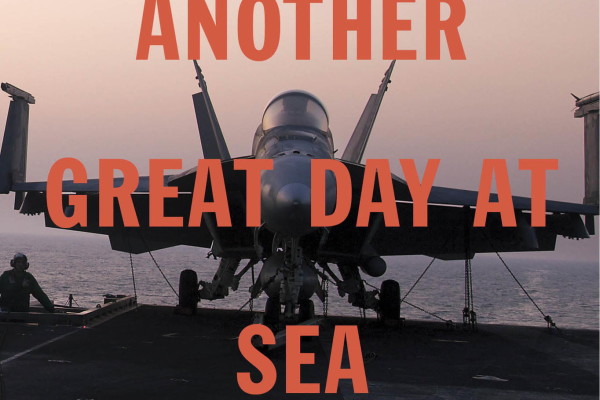

Another Great Day at Sea by Geoff Dyer

Towards the end of Geoff Dyer’s new book, Another Great Day at Sea, Dyer writes: “…the longer that I spent on the carrier, the more convinced I became that, of all the kinds writers I was not, ‘reporter’ was at the top of the list.”

The book is an account of the two weeks he spent on the air craft carrier USS George H W Bush as a writer-in-residence, and while Dyer’s observation about himself comes of as a self-deprecating dig at his writerly abilities, the statement works the opposite way when applied to the book as whole: his lack of reporting skills are at the heart of his tremendous talent as a story teller.

Because this book is about Geoff Dyer’s internal life: his meandering associations and the–what better word is there?–unique way he filters the world around him. The reader is not aboard the USS George H W Bush, she is aboard the USS Geoff Dyer, she is navigating the waters of his perceptions.

Late in the book, Dyer reveals the structure of the book: “So there I was: a tourist with a notebook…whose data was so thoroughly and distortingly mixed up with the means of obtaining it that it probably had no value as data, only as a memoir or a collection of camera-less holiday snaps.” Though the book is broken down by chapters, each one reads more as distinct snapshots of moments abroad the vessel rather than a continuous narrative carried through between sections.

In this snapshots, Dyer presents very little of exterior world: there are only a few interviews with crew members, brief sketches of the appearance of the air craft carrier–of the inside of the vessel, for instance, we only that is difficult for a tall man like Dyer to navigate the cramp passageways–and notably absent is a lack of physical action, save for Dyer’s constant stooping: though one assumes he must shake hands with the crew members he encounters, sit in chairs across from their desks, settle into his seat in the mess hall where he eats everyday, the book is almost entirely lacking in this type of action. The result is type of blindness, a Being John Malkovich-esque perception of the world, in which we bob around inside Dyer’s head disembodied and lost in thought.

I assume it would become tiresome to be trapped inside any other person’s head as he negotiates the minutiae of daily life aboard this vessel for 190 pages, but this is not the case for Dyer, who has crafted a persona so charming, I consumed this book in space of a couple days, mostly while riding the subway to work because I wanted this story to be the first one I encountered in the morning.

Dyer makes the point again and again that most of the 5,000 person crew have nothing to do and yet are always busy. They scrub and polish, monitor, guard, observe–and even those that fly, like the search and rescue teams aboard “helos,” continually circle the same side of the ship, chatting about football and waiting for the action to begin. It’s a strange sort of life, spending what often amounts to 15 hour days making sure that nothing happens, but Dyer is careful to highlight the passion and dedication the crew exhibits. There is nothing to mock in the lives of the people who have chosen to spend their lives aboard the ship.

Which is not to say that Dyer doesn’t often find himself disagreeing with some of the people he encounters. At the beginning of the book he attends a Pentecostal Bible study class, and becomes caught up in the attendees’ singing:

“I love gospel, especially like this, with no instruments, just uplifted American voices…within thirty seconds the atheist’s spirit was moved, tears trickling down his unbelieving cheeks…I could feel the happiness of it…it was a lovely hymn and when it ended, I could feel the whole halleljuah-ness of it in myself and the warmth that comes from being in the presence of good people.”

He describes the leader of the class as a “righteous, spiritual, decent man,” but that he had “pledged his light to darkness, had chosen ignorance rather than knowledge.” He and the photographer, whom he refers to throughout the book not by name, but only as “the snapper,” sneak out before the class ends.

It’s a powerful passage: Dyer acknowledges the power of faith, he feels it himself. But he can do all that and still remain committed to his own values, voicing them without remorse to a reader that depends on his skepticism, his cutting honesty.

Dyer can be sarcastic too though–it’s one of his clear strengths. Nearly every line is marked by his dry wit, but it’s the moments of reflection on his subjects that make this book an exceptional work. While lamenting the fact that there is no booze aboard, not for the first or last time, he wonders why the crew only talks of missing their families. “And what about other things: windows with views, trees, weekends going for a drive…” The list goes on. “No one mentioned this stuff–because they could not bear to? Because the torment of missing these things was so great that they could never be spoken of?”

For a man that spends so much of this book pondering how life on the aircraft carrier has affected his own life–often to hilarious and empathetic ends–it’s a compassionate moment. He breaks away from himself, if just briefly, and speaks a poignant truth about the secluded life of the naval officer.

There is just as much pleasure in the reading when his eye is turned inward, which is often, even when he is interviewing various officers. The food has a terrible effect on his digestion, he is terrified of pooping in toilets that are often malfunctioning, the absolute necessity of a basin to pee into in the middle of the night. As in Out of Sheer Rage, I find it striking how Dyer manages to sustain this constant interiority, which hovers near extremely narcissistic. In Another Great Day at Sea, Dyer is clearly uncomfortable physically–he must stoop whenever he walks around the ship to prevent injury, the noise is so loud it is, “beyond metaphor”–but also socially. He struggles to remember crew members ranks and titles, and he is not sure when he can crack a joke, and therefore most of them are awkward and ill-timed. He wants to be accepted but isn’t sure how to go about it, and that struggle is charming to read, not because the reader is supposed to feel especially sorry for Dyer, but because we know the feeling. He channels that anxious energy into vibrant prose that is always insightful even in his most irritating moments of selfishness.

The end of the book circles back to prayer, which for Dyer means “wanting the best for good people,” and it becomes clear that that selfishness is a facade, a surface level trick of Dyer’s personality that masks his underlying fascination not with himself but with other people, especially those with experiences radically different from his own–perhaps another symptom of his anxiety. Dyer doesn’t see establishments, he sees lives, which makes this less of a narrative about an aircraft carrier and, to it’s credit, more of an account of lives that would have gone unexamined were it not for Dyer’s curiosity.

—

Elisabeth Sherman is a writer living and working in New York City. Her work has appeared on Not So Popular and Tor. You can follow her on Twitter.