A short-haired woman leans on her right leg, her chin tilted up. She’s got something between a smirk and a frown on her lips. It’s 1970, and she’s at a protest in the Village wearing tight black jeans, assuming that sexy stance of toughness that is alluring across gender. Don’t fuck with me, she seems to say. Or do. The placard in her hand says it better, and in bold, scrawling capital letters: “I am your worst fear. I am your best fantasy.”

This iconic image, blown up to life size, greets you in the north gallery of the Leslie Lohman Museum in SoHo for the exhibition “Brave, Beautiful Outlaws: The Photographs of Donna Gottschalk,” on view until March 17. Gottschalk is responsible for the photographs that fill the room, but in this photograph, she is the subject, inviting you into her intimate world of working-class queerness with an enticing warning: you may find what you see and hear disturbing, and you may find it unbearably alluring.

The introductory image depicts an act of self-conscious courage and overt activism, but the majority of the images in the exhibition do something different: they depict politics as something lived every day, and family as something chosen and found. The images here are fine art, certainly, but also something like a photojournalism of the everyday, albeit of lives that were never allowed to be merely ordinary. The show provides a record of New York City before Stonewall, when being out was dangerous and illegal, but it is far from a miserablist parade of atrocities or a cloying celebration. The photographs instead depict women that we hardly ever get to see in a way we hardly ever get to see them: lesbians from the past, shot artfully and softly, living full lives.

Gottschalk grew up working class on the Lower East Side—her mother was a beautician and her father a merchant marine—and trained at an arts high school and then at Cooper Union. It was in high school that she befriended other lesbians for the first time, many of whom had been kicked out by their families and were now spending their evenings in gay bars and sleeping on the streets. At Cooper Union, a teacher gave Gottschalk an assignment to go see a show at the Museum of Modern Art, where she wandered into a room full of Diane Arbus photographs and saw outsiders depicted respectfully in art for the first time. Gottschalk describes Arbus’s work as “frank,” the same word she uses to talk about her own work. “She was taking pictures of people nobody wanted to take pictures of.” Those people were were, like Gottschalk, misfits—poor, queer, peripheral, and ignored.

One of the first images in “Brave, Beautiful Outlaws” portrays Gottschalk standing with three such women—her “girl gang”—looking up at the camera on a cramped fire escape. The photograph came from the first role of film Gottschalk ever shot, using the first camera she ever owned. It was shot by a friend outside the frame. Here is a group of women, butch and cool, looking like they’re a punk band, or the cast in a lesbian version of Rent, their faces young and yearning, one suppressing a smile as she leans against the brick building, holding a cigarette casually. They are fierce in their ordinariness; the working-class-lesbian-activist version of the female friend groups that have long populated the fiction of New York, looking up and towards a future, full of so much hope for a better life.

It was a hope that would never be fulfilled easily, or often at all, for Gottschalk and the other women she knew—Gottschalk was a working-class lesbian women in the 1960s and ’70s, far outside the mainstream art world or even avant-garde culture. She had been part of one group show in the ’70s, but never found a foothold in the art world or in the world of lesbian photography because, she suggests, her work was too melancholy for those activist times and she had no stomach for self-promotion. Instead, her money came from jobs driving a hansom cab in Central Park, nude modeling for artists, and eventually a photo processing business. She considered any job that allowed her to wear pants. It was an old girlfriend of Gottschalk’s—the activist Joan E. Biren—who, decades later, recalled that Gottschalk had often taken photographs during their relationship and asked Gottschalk if she still had any of those images. She did. Boxes of old negatives languished in Gottschalk’s Vermont farmhouse, many of which she had never developed. She sent scans to Biren, who brought them to the museum. At age 68, “Brave, Beautiful Outlaws” is Gottschalk’s first exhibition since the 1960s, and her first solo show.

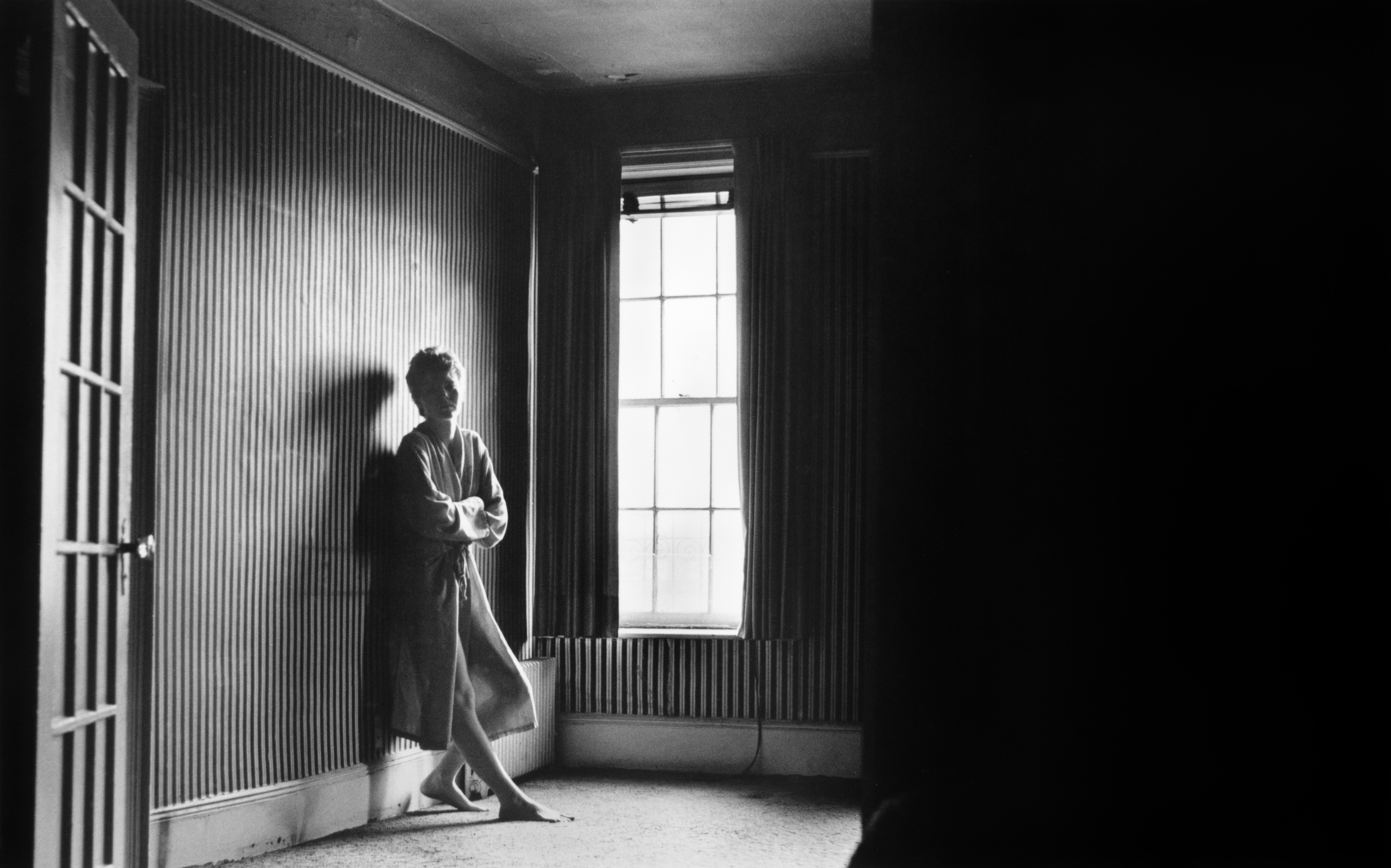

The exhibition progresses chronologically, through Gottschalk’s life, depicting lovers, friends, protests, children, and siblings. Gottschalk moves from New York to San Francisco, photographs a pigtailed lesbian auto-mechanic, documents a pilgrimage of lesbians to a Black Panther Conference in Pennsylvania, captures couples nude and entwined in each other’s arms. Many of the images are classical in their composition, the product of a self-consciously artistic eye—figures recline; Gottschalk herself leans against a wall, the light from a window highlighting her naked knee under a robe; a hand grasps an arm over a nude torso. The photographs are deeply intimate and, as Gottschalk herself says, frank: the people in them seem to reveal themselves eagerly. Taken in total, these images of working-class queer women offer a lesbian visual culture that has often been left out of the queer canon. Gottschalk is a woman looking at other women—sometimes lustily, sometimes longingly, sometimes with the tenderness of a sister or a friend.

The future inherited by the those documented in “Brave, Beautiful Outlaws” is a tragic one. Many of the people in this show were abandoned by their families, lost jobs for dressing too butch, lived on the streets as they struggled with mental illness. One such woman, Marlene, appears several times over the course of the show. “She was magnificently beautiful and brave and unusual. Marlene exposed herself to the hostile outside world more bluntly than anyone I had ever met, without much regard for the consequences,” Gottschalk explained in an interview. We see Marlene nude from the waist up as a young woman, grinning flirtatiously, arms crossed over her chest. Later, she sits on the back bumper of a car, covered in grease, tough but open. She and Gottschalk travelled cross-country together, friends in search of new horizons. But then, near the end of the exhibit, we see Marlene again, obese and struggling with mental and physical illness, a few years before her death. The show closes with a series of photographs of one of Gottschalk’s siblings, born Myla, born Alfie, who came out as gay and then transitioned from male to female. There is a romantic image of Myla as a young person wearing a velvet dress, sprawled across a bed and pushing beyond the frame. Next to it is an image—really, a document—of Myla’s face, lacerated and beaten, after a transphobic assault. Gottschalk took care of her four biological siblings, and many other found siblings as well, paying their rent, helping them get on their feet, and then, finally, holding them as they grew sick from disease, and from the poverty and neglect that comes with it. One sister, Mary, died of a botched chemo treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma; Myla died of complications related to AIDS in 2013.

One can’t help but feel Gottschalk wanting to gather up these siblings, friends, and lovers, trying to care for them, to save them, in part by bearing witness to them with a fullness and compassion that they rarely experienced in life. The harshness of the lives of her subjects is met with a gaze that is soft, even tender. These are not specimens or outsiders. They are family, known and loved. Existing somewhere between the profound ordinariness of the family snapshot and the skillful eye of the art photographer, the photographs in this exhibition demonstrate the intersections between beauty and politics, care and revolution. The work on the walls of the gallery show a kind of love that is the best fantasy of what family can be.

Photo credits:

Donna Gottschalk, Self-Portrait with striped wallpaper, 1978, New York, silver gelatin print/ 2017, 14 x 11 in. Collection of the Leslie-Lohman Museum. Museum purchase in honor of Meryl Allison.

Donna Gottschalk, Marlene, New York, 1969, silver gelatin print/ 2017, 16 x 20 in. Courtesy the Artist.