“This is my skin. This is not your skin, yet you are still under it.” – Iain Thomas

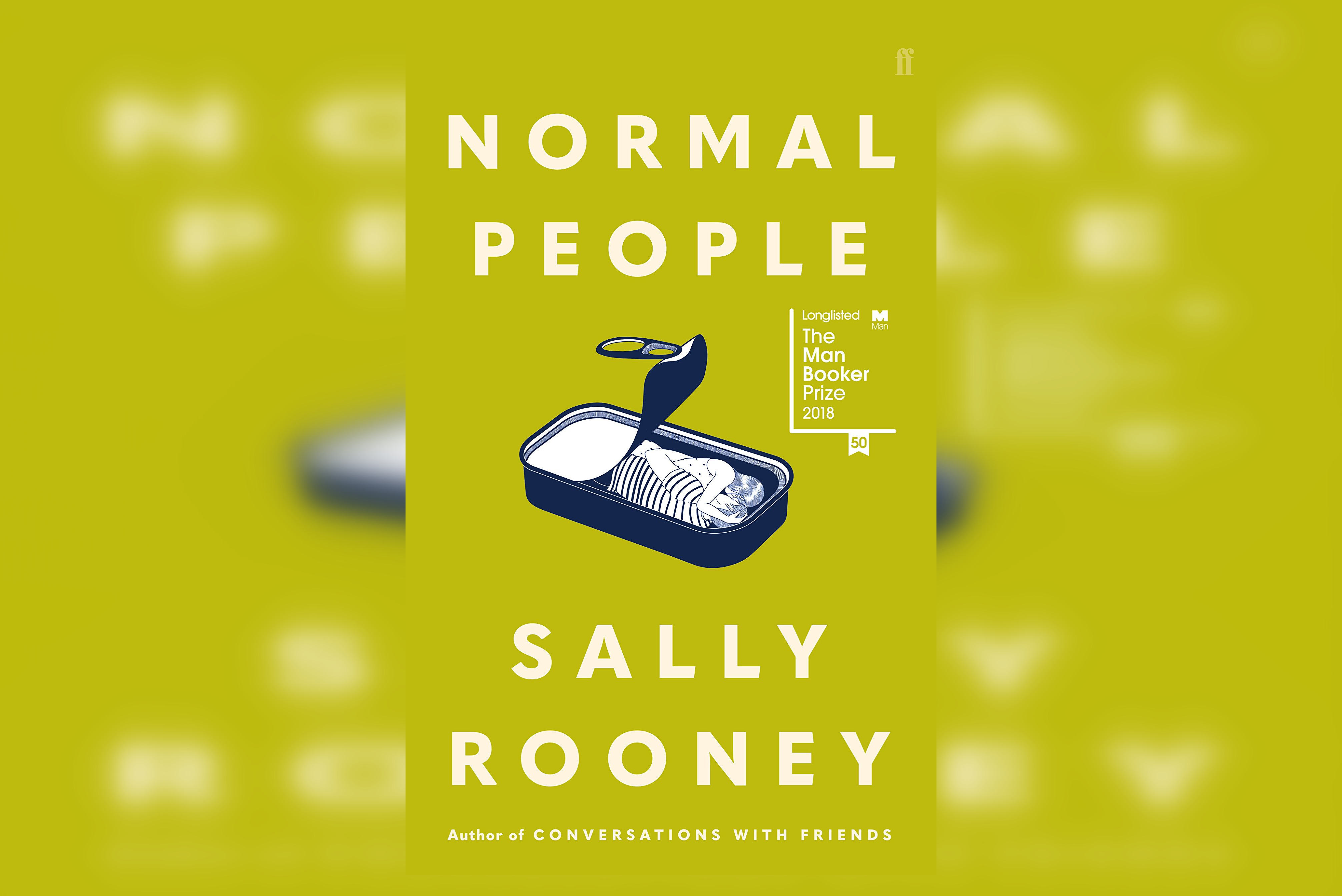

Nobody in Sally Rooney’s new novel Normal People—an addictive account of the relationship between two brainy college students—would ever use the word “intimacy.” The characters, mostly students at Dublin’s prestigious Trinity College, are too cool and/or too self-effacing for earnest lexicon. They lampoon monogamy while drinking seemingly bottomless glasses of red wine, invoke threesomes, and poke fun at the patriarchy. (“[Men] control the whole social system and this is the best they can come up with for themselves? They’re not even having fun.”) But when it comes to their own feelings, they are infuriatingly coy. They fumble over each other’s and repress their own.

Normal People is a moodier and tighter novel than twenty-eight-year-old Rooney’s debut novel, Conversations with Friends (2017); the story begins in high school and never loses the delicious gravitas of angst. It could be named Things that Don’t Come Up in Conversations with Friends. To list a few: crushing class anxiety, the lasting damage of childhood abuse, sincere political ardor. But Rooney’s most robust subject, and arguably her most taboo, is the unsettling effect of real human intimacy.

Normal People tells the love story of Marianne and Connell, who grew up in a small town in western Ireland. Marianne, from a wealthy family, is unpopular in school. Connell, whose mother cleans Marianne’s house, is a well-liked star football player. One day they kiss after flirting over a copy of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (Connell is secretly bookish). From there, in the words of F. Scott Fitzgerald, “they slipped briskly into an intimacy from which they never recovered.” Rightly so.

If Kristen Roupenian’s viral New Yorker story “Cat Person” was an object-lesson in the dangers of sex without intimacy—repulsion, violation, self-recrimination—then Normal People examines intimacy’s profound impact on the soul. In an interview, Rooney says that she is interested in intimacy as discomfort and the loss of self, “of being penetrated literally but also psychologically.” She depicts this cannily through descriptions of bodies. After Connell has sex with Marianne for the first time, thoughts of her “small wet mouth” threaten to prevent him from breathing. Her total availability overwhelms him: “He kisses her again and she feels his hands on her body. She is an abyss that he can reach into, an empty space for him to fill.”

Rooney posits that true intimacy leads to self-annihilation, a fate that Marianne desires and Connell resists. Rooney calls our bluff when we say we want love. Look, she gestures, is this really what you want?