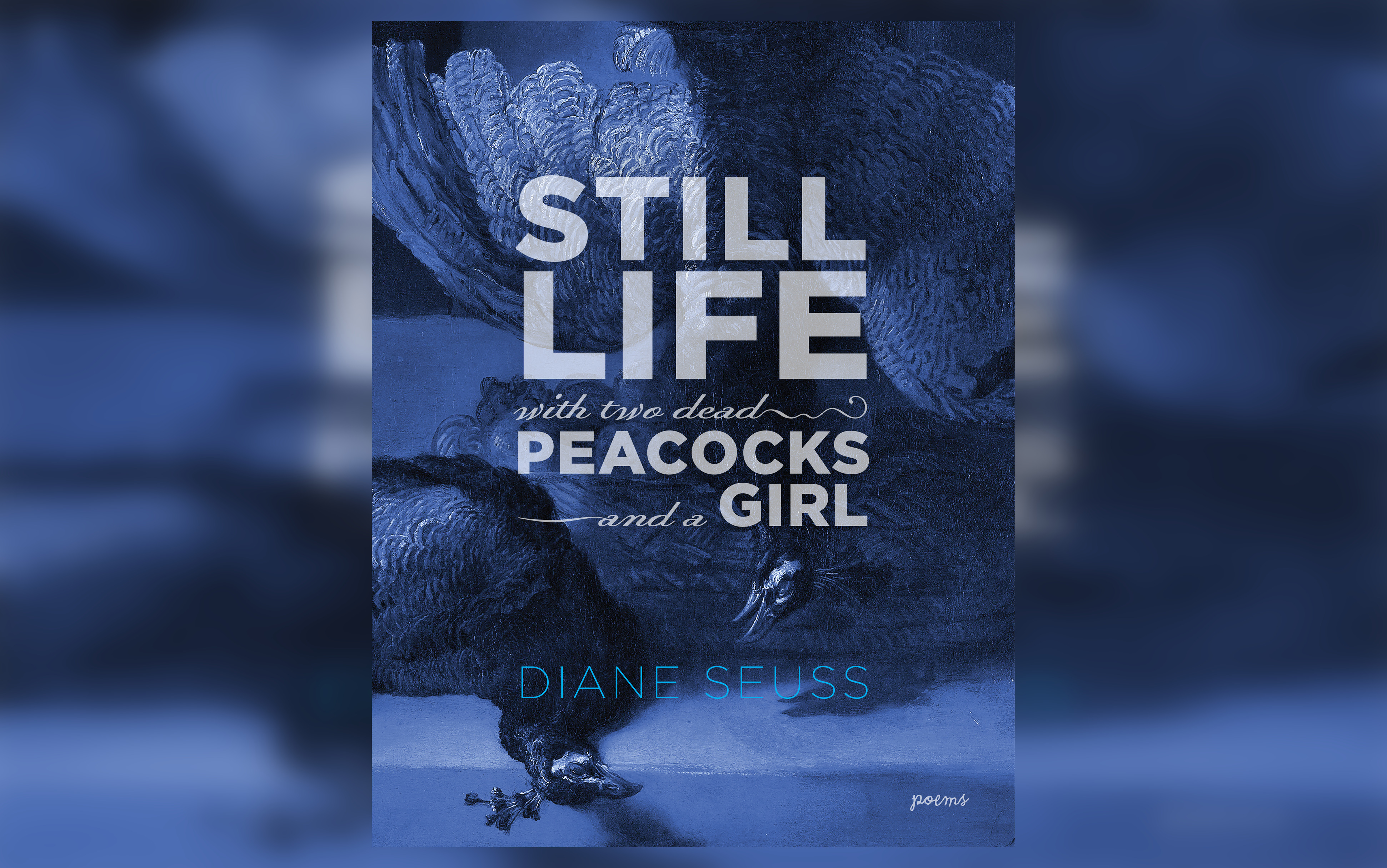

Sharing a title with a painting by Rembrandt, Diane Seuss’ fourth collection is a sensual bricolage of the exalted mixed with the mundane. Through the usage of self-portraiture as a confessional device and ekphrasis about fixtures in the Western canon, Seuss questions the politics of the gaze: who is able to see and at what cost? The collection is inscribed “To stillness. To life.” Long lines, syncopated sentences, and melodic repetition mimic optic travel. Images are brought to life and then mutated into the next. By presenting the inanimate as animate, and vice versa, the poet questions how experiences and memory, similar to visual art, are framed, and at times, concealed and censored.

Seuss’ approach to where and how “art” lives belong in the same intellectual sisterhood as Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation.” In “Walmart Parking Lot,” Seuss divides the poem into sections named after American artists such as Pollock, Rothko, and O’Keefe. The poem enacts a mordant commentary on our culture’s fixation with curation by juxtaposing darlings of the “highbrow” in proximity to working-class Americana. The Andy Warhol section catalogs fixtures of ‘00 pop culture by the way of frosted tips, lipgloss, and barbwire tattoos. In the fragment named after Rothko, Seuss likens the observation of art to a learned performance “Some of us would take the South Shore to Chicago to see art. We’d stand in/ front of large canvases in palatial museums, speaking to each other in/invented languages.” Later, in the poem “Memento Mori,” Seuss offers how emotion, such as grief, can be marred by adherence to a social protocol “I saw/ my father carried from the couch into the waiting ambulance/ which wailed like my mother could not, like I did not/ as wailing is is an art, its permissions, learned.” Seuss’ poems then participate in an unlearning by wavering through images of paradise contrasted with hell, violence in relationship to domesticity, and images where the crafted transforms into the organic and back again.

In the poem that serves as the collection’s namesake, the last sentence proclaims “Art, useless as tits on a boar.” The collection never fully offers a philosophical aesthetic platform. Instead, the reader is permitted to splash around in various visual pools. Where the collection does deep dive is into the predicament of sensory experience: “My eyes were hungry for paint, like I used to imagine/ a horse could taste the green in its mouth.” In the eponymous poem, the girl on an imagined search for pie finds two dead peacocks, birds known for their visual bravado. Yet, what can something dazzling, inanimate and inedible offer us? Well, this collection is a banquet.

Photo Credit: Graywolf Press