Today, the news media is the main site of contention for how China gets represented. But what about translations of classical Chinese poetry? These translations, along with their negotiations of incommensurable values, institutions and histories, are some of the best kindling we have for discussions on how the English-speaking world understands China. In their process of interpreting and learning from the ancient Chinese verses, poets from William Carlos Williams to Chloe Garcia Roberts have also created new possibilities for what we can convey in English.

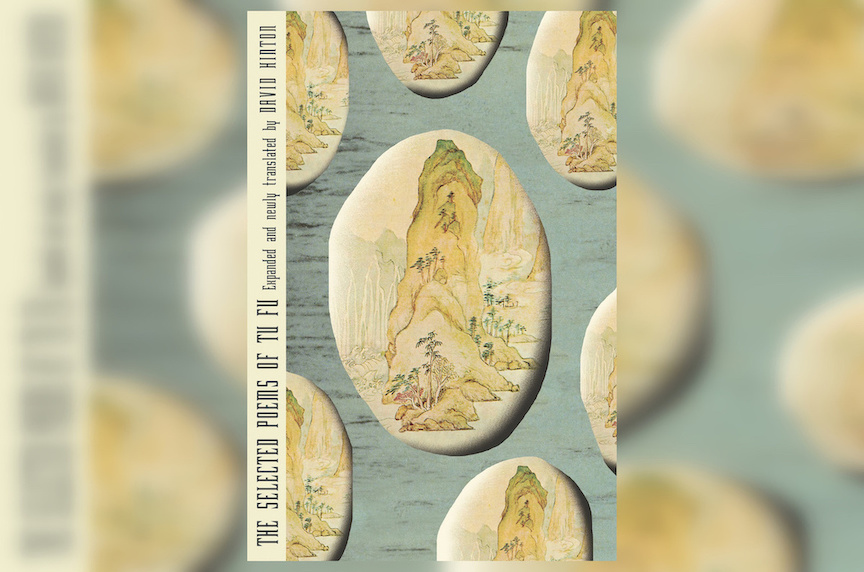

David Hinton’s Selected Poems of Tu Fu: Expanded and Newly Translated (New Directions, February 2020) is the newest addition to our dialogue with Chinese antiquity. As a reinterpretation, this book comes three decades after Hinton’s original Selected Poems of Tu Fu (1989). During this time, Hinton translated the seminal works of Chinese philosophy from Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching to Confucius’ Analects, the Zen Buddhist koans of the No-Gate Gateway, and dozens of canonical works from the Chinese poetic tradition from the 15th century B.C.E. to the 13th century. With a deeper understanding of the language and the facts of Tu Fu’s life, Hinton returns to the first poet that he translated.

Tu Fu 杜甫 (712–770) was a failed civil servant who spent much of his life as a refugee as he watched the Tang establishment’s collapse. His best-known works depict endless wars on the borders, peasants forced to man the armies, and his own separation from home and family. He wrote satires on the lavish lifestyles of the emperor’s friends and concubines. “Behind red gates, the stench of spoiled meat; on the street, bones of frozen dead” has become a timeless articulation in the Chinese idiom of the end-of-dynasty outrage.

Hinton’s precedent, Kenneth Rexroth, translated dozens of Tu Fu poems during a time when Ezra Pound’s Li Po still seemed to speak for all Tang poetry. In Classics Revisited (1968), Rexroth compares Tu Fu to Baudelaire and Sappho, praising their shared “exacerbated sensibility,” “exile’s nostalgia,” and poetry of “elegiac reverie”—assessments indicative of Rexroth’s troubled outlook for his own country. Hinton’s translations, though, are more informed by the spiritual insights of Taoism and Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism. Here’s his new translation of a poem Tu Fu wrote while trapped in the capital, then fallen to rebel armies:

Facing Snow 對雪

Enough new ghosts to mourn any war,

and a lone old grief-sung man. Broken

clouds at twilight’s ragged edge, wind

buffets a dance of frenzied snow. Ladle

beside my jar drained of emerald wine,

flame-red illusion lingers in the stove.

News comes from nowhere. I sit spirit-

wounded, trace words empty onto sky.

戰哭多新鬼

愁吟獨老翁

亂雲低薄暮

急雪舞回風

瓢棄樽無綠

爐存火似紅

數州消息斷

愁坐正書空

It’s worth noting how Hinton’s translation has changed. Here’s the poem’s third line, for example, with my cribs and Hinton’s versions:

亂雲低薄暮

[disorderly] [clouds] [low] [twilight]

“clouds at / twilight’s ragged edge foundering” (1989)

“broken / clouds at twilight’s ragged edge” (2020)

In both cases, the enjambment slows down the reading and almost hints at the unsaid density of the original. “Broken” is a deft interpretation of luan 亂, superior in sound and image to “foundering,” not to mention the unnecessary delay between “foundering” and the clouds it modifies. This line is particularly tricky because “low” 低 says little about where the clouds are in relation to the twilight. With no copula, preposition, or conjunction, the translator is left to fill in the grammatical emptiness. Do “Ragged clouds press down in the fading twilight” (Burton Watson)? Do “Tumultuous clouds lower toward twilight”, as pictured by Stephen Owen? Kenneth Rexroth does away with clouds altogether: “Ragged mist settles / In the spreading dusk.” In his versions, Hinton simply uses at, but “Twilight’s ragged edge” elegantly extends the speaker’s vision toward the uncertain meeting point between land and sky.

The interpretive problem in this line recalls a similar one in Wang Wei’s 王維 “Deer Park” 鹿柴, made famous by Eliot Weinberger’s 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei. The poem’s fourth line, partly a description of sunlight, is a litmus test for how translators play with ambiguity: 復照青苔上 [again] [shine] [green] [moss] [above/on/top]. Hinton’s interpretation of the line shows that he has spent time in the woods, where a patch of light on a boulder moves upwards with the approach of evening: “late sunlight / flares on green moss again, and rises.”

A more telling revision is in the poem’s last clause from “tracing words onto air” (1989) to the more complicated “trace words empty onto sky” (2020). In the key terms section, Hinton notes that the word empty 空 often describes “consciousness emptied of all contents.” This conceptual framework, which was not present in the 1989 edition, is the fine-tuned lens through which Hinton has translated new poems and refined old ones. His introduction, reading guide, endnotes, and key terms are indispensable to the book’s architecture. We can only understand a line like “Dark-enigma winter bleeds through dark-enigma’s yin-dark / frontiers” (方冬合沓玄陰塞) after reading Hinton’s explanations of Taoist and Ch’an philosophical concepts, which most contemporary Chinese readers would not be familiar with.

Of course, many of Hinton’s translations can be easily read without the supporting discussions. The poems that do require this background tend to create their meaning slowly, like a guided meditation. In fact, Hinton claims that many of Tu Fu’s landscape poems mirror the process of meditation, during which we watch “the form of thought arising from emptiness and disappearing back into it”—just as things in nature appear from and disappear back into the ground. Hinton’s word choices are consistent across all of his translations, from the Tao Te Ching (2001) to The Late Poems of Wang An-Shih (2015). “Dark-enigma,” for example, is Hinton’s translation of xuan 玄: “equivalent to Absence—the generative tissue from which the ten thousand things spring—but Absence before it is named. For once we name it, we have entered the realm of the differentiated and therefore lost it.”

Tu Fu was not a Buddhist, but one can certainly reconstruct his poetry using Buddhist (or Marxist, or feminist, or deconstructive, or cornucopian) terms and values. “Stars suddenly there, sparse, next aren’t” is a line from Hinton’s 1989 translation of “Sleepless Night” 倦夜. In a poem about Tu Fu’s fears for his country, the line offers a metaphor of similar strain to Shakespeare’s “When yellow leaves, or none, or few.” The line takes up a metaphysical register, though, in the 2020 translation: “Sparse stars / Kindle Presence—then darken into Absence.” In addition to “Presence” and “Absence,” the word “sparse” is also explained later as a key term. In comparison, Rexroth’s version seems light as a breeze: “One by one the stars go out.” Hinton, at the risk of alienating his reader, is not interested in domesticating the poems or translating their “apparent content.” Instead, he seeks to interpret the cosmology underpinning Tu Fu’s language. For that, his scholarship warrants our attention.

In China, Tu Fu’s verses continue to arise in daily conversation. They decorate the walls of homes and offices, are memorized by grade-schoolers, and travel across borders, nostalgically recited by expatriates. What do these poems mean to them? Hinton’s approach, as well as the book’s subtitle, “Expanded and Newly Translated,” gestures to an ongoingness, an endless number of ways to present Tu Fu’s poetry—but here is one Tu Fu to which many readers will turn for times to come.

![“Party 1-8” from Sexual Equilibrium of Money by MID [Mita Dimitrijević] Translated from the Serbo-Croatian by Steven Teref and Maja Teref](http://archive.columbiajournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MID-Sexual-Equilibrium-of-Money-2-445x400.png)