Last week, I visited your grandmother by the lake. She boiled a pan of milk and held our son. In her arms, he was quiet and not the despot we have come to know. She asked after you. I said that you have not been well. That the grooves beneath your eyes have deepened, that you are sleeping for days at a time. She said you should come to the lake. I did not mention the hardening of your skin, the figures in your sketchbook.

Your grandmother’s kitchen was suffused with lilac and pepper. Steam from the pan rose to fog the windows. Snowfall blurred into lines against the night. The sycamores were heavy with ice. Every so often, it would fall onto the roof, and the house would shudder. Our son would tighten his grip on my thumb.

When we arrived, I slept in your bed. Though years had passed since your childhood, the frame reminded me of you. I had not connected you with birch, but there it was. Perhaps the beds in which we sleep as children leave on our bodies some lasting scent.

That night, I dreamed of a field of statues. Grass grew in the spaces between the toes of men. The ground began to tremble. It was an earthquake. Heels sank into the ground. Colorless fingertips and ears collapsed into mounds. I beheld it from below, so much chaos.

In the morning, I shrouded myself in your blanket. Our son was still asleep. Classical music drifted from your grandmother’s room. Pulling your sketchbook from beneath my pillow, I tucked it beneath my arm. I would walk to the lake.

Beyond the doorway, snow dusted my slippers. Walking slowly, as in a dream, I reached the banks. Winter veiled the water. Strange shapes jutted from the surface, small evidence of life: wings, talons, and beaks. And from the perimeter: paws, muzzles, and paunches.

At such a sight, I felt ephemeral.

Where do the edges of my body begin, and yours end?

As our son grows, my eyes become attuned to the slight. His hands are lined with wrinkles. His eyes are marked with colors for which I have no language.

The lake held my attention. Water moved beneath the surface, propelling blocks of ice. I found I could name the animals as they emerged in parts. Here a mammal, there a bird. An eagle’s wing reached the edge. I approached it and pulled it from below. It was attached to neck and body, the sinews of which seemed to be made of stone.

My thoughts turned to your sketchbook. It is full of creatures in awkward positions, folded limbs and beaks, shaded eyes. When I confronted you, saying that you had no right to hide these pages of beauty from me, your face shut like a guillotine. You said that you would not speak of it.

Now I understand. You do not have much time.

In a grove, I found a sparrow. She was perched on a vine. I placed her in the palm of my hand. Her belly was round and cold. I wrapped her in the edge of my blanket and held her to my side. I pressed her, pushed against my skin, until she was sure to bruise me.

We were expecting when your illness emerged. You were sleeping at my back. Your breathing stopped for a moment. Your heart had paused, you said. Something knocked against it. A hardness within the chest. Months passed, and you told me of a callous, forming at your breastbone, spreading across the skin.

Would a doctor have prevented you from solidifying?

The midwife rubbed my hands with oil. Our son grew inside me, and I learned to be still when I felt a rush of movement.

We fought. Where our bodies touched, your blunt fingers would dig into me. You once hit me. Your face had stiffened into a mask. The callous had extended and thickened. Your voice became rough, almost indiscernible, as you said, I will never. I will never again. Your eyes faded from green to gray. You lost your ability to see in gradients.

When I returned to your grandmother’s house, she was cooking. She snapped chicken bones, one by one, into the pot on the stove. Our son was propped against the dishwashing basin, watching. Moisture moved along his cheek. Unwrapping the sparrow from your blanket, I placed her on the counter. Our son traced the ridges of the wings folded against her body.

Your grandmother and I sat in kitchen chairs, drinking soup from stone mugs. Ice fell onto the roof. She understands, she told me, and looked into the empty space of her home.

Our son smiled, and he threw the sparrow onto the floor.

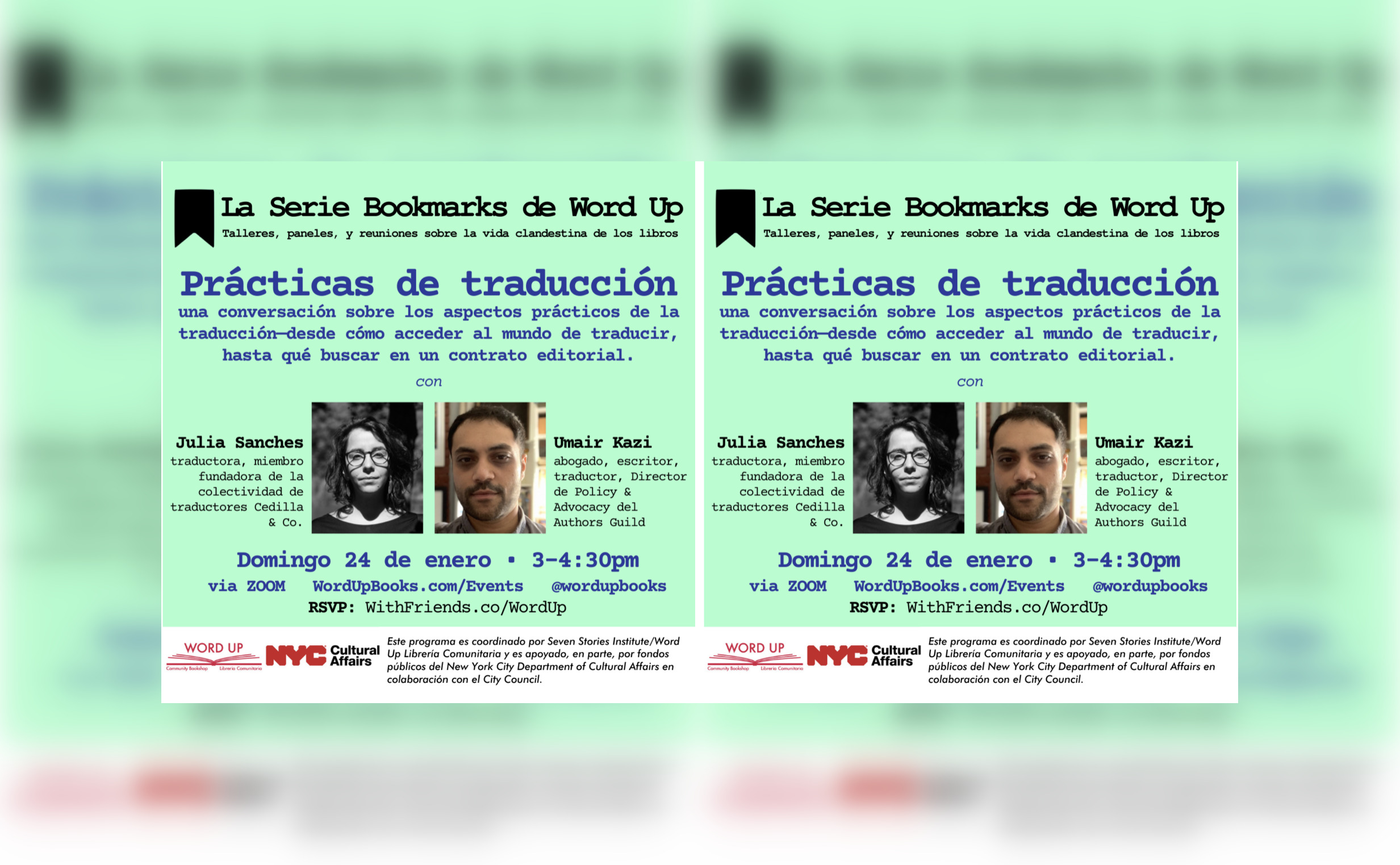

Photo Credit: avilarchik via Creative Commons