Julie and I are in the field behind our houses. The day is dimming quickly but quietly — one second it was afternoon and now it’s almost night. The two of us are catching fireflies with our hands and sticking them in an old pickle jar. Over our heads, bats swoop, their little bodies black against the purpling sky. They’re chasing the mosquitoes that keep screaming in our ears. This is the kind of thing our science teacher, Ms. Duprey, would tell us to thank the bats for. She would say the bats, even though they’re scary, serve a purpose because they limit the population of bugs and insects that can bite us and ruin our plants and houses. I’m not afraid of the bats or the screeching mosquitoes. I’m at a point, though I won’t realize this until later, when there is too much to be afraid of, when I have to choose what to care about and what not to care about, and scary creatures just don’t make the cut.

Once Julie and I have caught enough of the fireflies—she calls them lightning bugs because she moved here from somewhere else—it’s time for the next part of our plan. The fireflies glow on and off, sending distress signals to no one as they float in the jar at our feet. Also at our feet is the box of tampons we took from Julie’s bathroom. The box has three compartments, each holding tampons of a slightly different thickness.

“Why does your mom need three sizes of tampons?” I say to Julie, who is pulling out the thinnest ones.

“I don’t know, maybe her vagina changes size sometimes.”

“Why would it change size?”

Julie looks up at me and shrugs. “The weather?” she says.

She and I unwrap the tampons she’s pulled out. We figure out how to release the soft, cottony bodies from their cardboard casing. There are a lot of tampons on the ground. They remind me of very skinny white mice, the way their strings curl behind them like tails. Julie and I are comfortable doing this to tampons because we are eleven years old and haven’t yet had that terrible, stranded feeling of reaching for a tampon when you need one only to find it isn’t there, the feeling her poor mother will probably have when she finds out the entire box is missing, Julie having taken them for other, less urgent purposes.

It is now officially dark, and the jarred fireflies’ plaintive blinking has strengthened in contrast. Normally I would need to be home by now, but Mrs. Little has been staying with me and my little brother for the past week or so and she’s old and doesn’t know any better.

Mrs. Little is staying with us because my mother is in the hospital and my father is there with her. My mother’s sick, I know that, but I don’t know yet that she’s dying. I know she hasn’t felt well in a long time because she has cancer, but I don’t know she fainted last week and my father found her on the bathroom floor. I know, because I’ve been visiting her every afternoon in the hospital, that her skin is yellowish and tight on her bones, but I don’t know her skin is that way because of her liver, which stopped processing the pills she was taking to help her sleep through the nausea from her aggressive treatment, and when her liver stopped processing the pills it meant her organs were shutting down, one after the other. I know things have been going wrong for my family lately. I don’t know my mother has only eight days left to live.

Julie opens the jar and holds her hand over its mouth like she’s trying to keep it from telling a secret. She doesn’t need to be home yet, either, but it’s because she just has a mom, no dad, and her mom is always too tired to make her and her sister do anything other than exactly what they want to do. This is one way that having one parent can go—not enough attention, not enough watching. Soon I’ll find out the other way it can go. After my mother dies, my father will hold my brother and me so tight and so close that we’ll barely be able to breathe until, for a few years at least, we’ll have to pry ourselves away and avoid his grasp all together, finding lives of our own beyond his careful planning of them, making terrible mistakes just because they’re our mistakes to make.

“Get ready,” Julie says, looking at me seriously. “I’ll move my hand so you can reach in real quick and grab one.”

“Ok.” I squat by the jar and try to look serious, too, so she knows she can trust me.

“1…2…3!” Julie hinges her hand open and I reach in. I feel like I’m doing something dangerous—my heart’s beating really fast—even though I know I’m not. My fingers hit one of their bodies and I pull it into my palm. I take my hand out quickly so Julie can get the lid back onto the jar.

“Okay,” she says. “Now rub its butt on this.” She hands me a cardboard tube.

The firefly is throwing itself weakly against the soft walls of my hand.

“Come on,” she says, “just pick it up with your fingers and rub.”

Holding the tube in my teeth, I try to get the firefly between my fingers. I open my fist a little bit and a neon glow throbs from the soft cave of my hand. I get the bug between my pointer finger and my thumb, then open my hand all the way. Unlit, the firefly just looks like a beetle—you would never guess it did anything as miraculous as glow in the dark. I take the cardboard tube from my mouth and try to plan a method for rubbing the firefly’s butt on it.

“God, you’re so slow,” Julie says.

“Will this kill it?”

“Don’t think so.”

I know she’s lying.

“Here, want me to do it?”

I don’t want anyone to do it, but I nod and let Julie take the little body from my fingers. Holding the firefly by its head, she rubs its light along one of the cardboard tubes. It works—there’s a glowing radioactive-looking smear all the way up one side.

“See,” she says. “It’s like a glow stick.”

Julie shakes her hand and the firefly falls to the ground. She doesn’t even notice. She’s already squatting to snatch another one from the jar. I grope around and pick up the dead firefly, holding it in my palm. I’m fine killing a mosquito or a bee, but there’s something different about this, this casual distinguishing of a harmless life. I have a pit in my stomach that I’ve been feeling a lot lately, especially every time I go to visit my mom in the hospital and I see her lying in bed like a bug herself, trapped in a web of tubes and wires.

“It’s dead,” I say. The firefly is lighter now. It’s lost its heft—by dying it has somehow become less dense, less consequential to the palm of my hand. “You killed it.”

“So?” Julie says, the darkness of her fist closing around another light.

I turn from the captured fireflies to the ones that are still free, floating in the air above the field, their lights brightening, then extinguishing, then brightening again. Each time the glow goes out it’s sudden, like a snuffed flame, and it feels like it will stay gone forever. Somehow, though, it always comes back, just as bright as it was before, fighting the dark in its own small way.

—

Heather Wells Peterson is a third-year MFA student in Fiction at the University of Florida. She is currently at work on a novel.

—

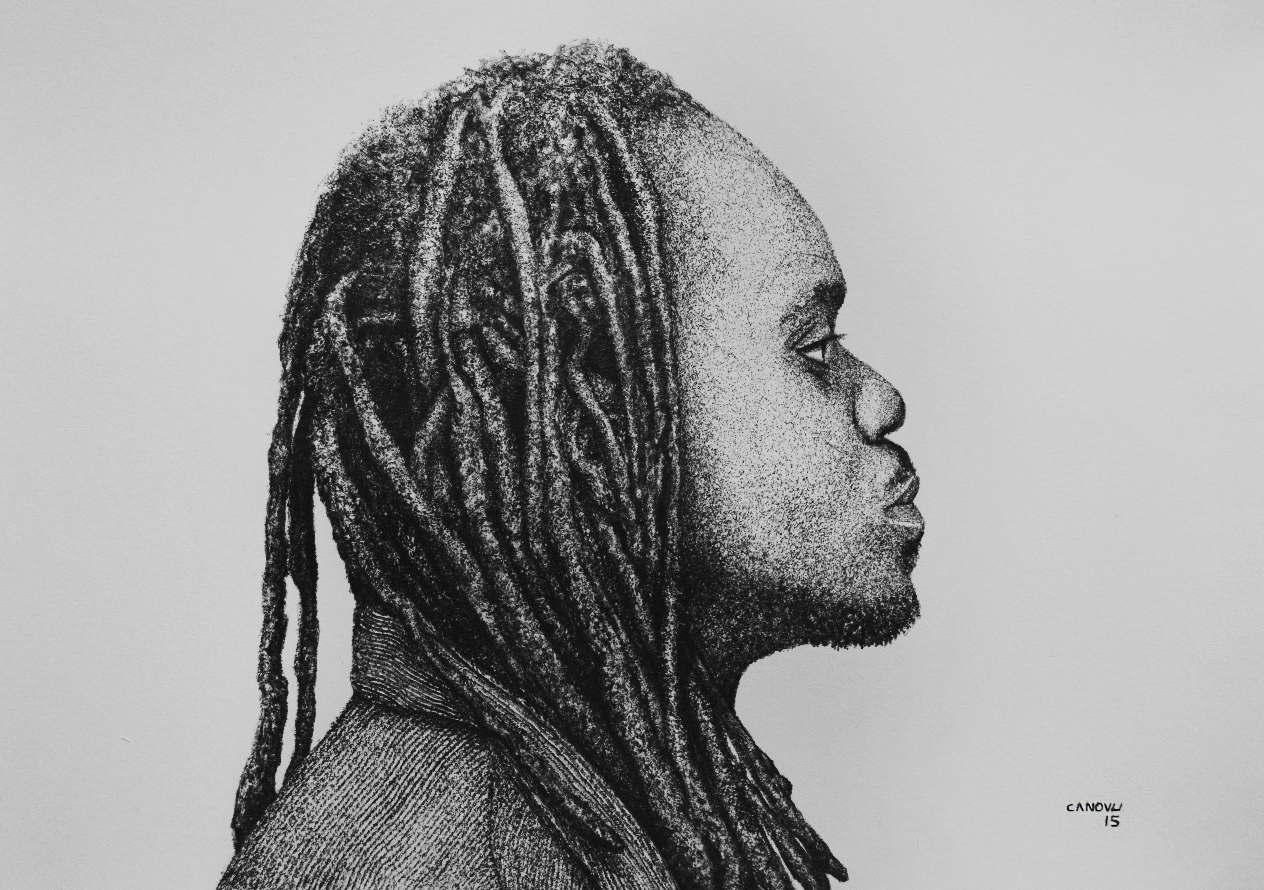

Featured Image photograph by E.B. Bartels, www.ebbartels.com.