Marcel Proust and Swann’s Way: 100th Anniversary exhibition at The Morgan Library and Museum. Exhibit through April 28.

Review by Beth Livermore

Bibliotheque Nationale de France (BnF), Paris, France

I had just read In Search of Lost Time, the seven-volume novel by Marcel Proust. By all measures, this is one of literature’s most important works. So I looked forward to the upcoming Proust exhibit at the Morgan Library with great anticipation.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of Swann’s Way, the first installment of this epic novel, curator Antoine Campagnon borrowed from the Biblioteque Nationale de France a selection of the author’s notebooks, manuscripts, and galley proofs to “provide unique insight into Proust’s creative process and the birth of his masterpiece.” Also on view would be period photographs of important people and places to Proust, plus letters to his mother.

Sadly, I was underwhelmed on arrival. The displays seemed meager. About six Plexiglas cubes that contained notebooks and manuscripts alternated with wall space hung with black and white images. This seemed strangely austere, even antiseptic, given this author’s penchant for detail, texture, and volume.

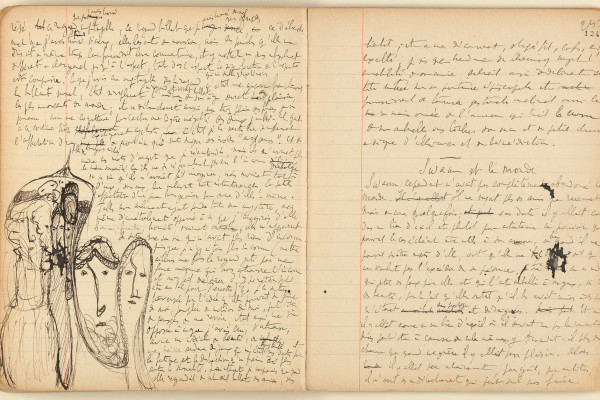

But the biggest disappointment was yet to come. The notebooks and other writings, which were obviously produced in French, were not accompanied by complete translations. My rudimentary French is hardly sufficient to appreciate the fullness and subtlety of the materials. Proust’s penmanship is no better than my own, making cross outs, write overs, and marginal notations, of which there were many, undecipherable. The excerpts that were included were maddeningly short, highlighting a single line or paragraph.

How sad, I thought, to stand so close to Proust’s original work, to the mind of a master, to the Rosetta stone of his process, and see so little.

I was not alone in my malaise. Every few minutes visitors would push through the double glass doors to this frigid little room, perhaps cooler than most galleries for hosting so few warm bodies. None stayed long, at least during my visit. They’d start off well enough, reading the introductory wall plate with a kind of reverence ordinarily reserved for places of worship. Then they’d tiptoe over to the first display, a portrait of Madame Proust and her two sons.

“I’m surprised,” said one young sophisticate, riding high on black boots, a cape slung over her shoulder. “Maman looks … I don’t know … indifferent.” Indeed, she looks oddly detached, sitting between the sons she revered, but staring off to the side, seemingly bored, waiting to be excused. The caption notes her influence on Proust; how his crushing grief for Jeanne Proust, née Weil (1849-1905), was a catalyst for his master work.

Some visitors also noted that Robert, with his nonchalant posture, his dark, romantic eyes could be mistaken for Marcel, who stood forward and forthright, like a jaunty society gent.

But most visitors began to lose interest after display number two. This is where several cahiers, given to Marcel by Bizet’s widow, lay open before them. These notebooks contained precious first notes for “Du Côté de Chez Swann.” But there was no way to penetrate the writings. Upon realizing this, most people looked bewildered, as if saying “Really? This is all?” They drifted about the room lighting now and then, like bumblebees searching for orchids but finding ordinary daisies, at best. Minutes later they’d leave for Degas, or lunch, or the Morgan’s well-stocked gift shop.

“My sister read the entire novel in college,” said one young lady to the next. “She says it changed her life.”

“How so,” said the other, holding the exit door for her friend.

“I don’t know.”

I decided to stay because I am a Proust fan—and I had made the long trip to midtown, which I loathe, just to see this show. Proust reveals human nature, life patterns, the value of authenticity, the reason for art, and the role of involuntary memory in his work. He shows us the magic of metaphor, the unbound shapes of sentences, the delight of full, unhurried description, and how an author’s perspicacity can provoke epiphany in readers. Surely I could find something revelatory in this room. A single object, perhaps?

In the end I was glad for my tenacity. As a writer I saw plenty.

First, the postcards and photographs served to remind me that fiction springs from reality. Proust modeled Combray on his ancestral home Illiers, Swann’s estate on his Uncle Jules Amiot’s expansive gardens, his party scenes on his social circle, and encounters with Swann’s daughter Gilberte on flirtations with a Russian girl he met in the Champs-Élysées, where he played most days after school. Proust did more than borrow inspiration from his life. He built castles in his mind from bricks of reality.

Furthermore Proust’s notebooks provided an intimate glance at this “writer-at-work.” They looked remarkably like my own notes, with bits of fluid text mingled with scratch outs, underlines, copious misspellings, and scribbles in the margin. And, you can see him working out the shape of his project. “Should it be a novel?” he asked. Or, is this “…a philosophical essay?” Proust even questions himself. “Am I novelist?”

His manuscripts were also revealing. There was nothing magic here. Just paper and words, just like mine. This showed me that Proust faced the same peril and uncertainty that we all do when staring at the page. All words are mutable. In one early draft, the famous madeleine that would be his portal to the past, access to a universe, was first no more than a slice of “toast,” later “biscottes.” Even Proust’s galley-proofs were at risk of last minute edits. On two occasions whole sections were cut and set aside as scrap. Luckily, Proust recovered them later, making one the opening to Within a Budding Grove. The other he published in Place-Names, in 1913.

I was also reminded by looking at the journals, manuscripts and galleys that while technology will change publishing, it will never alter the basic process of writing. Proust handwrote his drafts and typed his manuscripts. Now, most of us use computers to draft or revise, or both. But we still make notes to ourselves, move copy blocks and revise eternally, stopping only for deadlines or maybe for sanity.

Still, the most important exhibit of the whole show for me was the final box in the center of the room. Here Proust’s first published copies of In Search of Lost Time sat in a box. The binding is curiously simple: cardboard covers, only font shifts and size changes to doll things up. The caption reminds me that Proust published Swann’s Way with Bernard Grasset at his own expense, after being rejected by Gallimard, Fasquelle, and Ollendorff. Now that’s commitment, I thought.

Robert published the remaining three volumes of In Search of Lost Time in 1927, five years after Marcel’s death. Then, the novel was a smash hit, consuming Paris and parts of the educated world.

Edith Wharton wrote to Henry James: “I began to read languidly, and felt myself, after two pages, in the hands of a master, and as presently trembling with the excitement which only genius can impart.” She later notes that James, to whom she sent the book, “recognized a new mastery, a new vision and a structural design as yet unintelligible to him but as surely there as the hard bone under the soft flesh in a living organism.”

I left the room shivering, probably due to overly cool air temperature. But also I was moved. For in the end, I saw the design behind this show, as ambitious as any work in miniature. Like Marcel’s novels, which require time and attention to detail to truly appreciate, it built gradually to an illuminative end with lasting afterglow.

Proust said that artistic reality is “a relation, law joining different facts.” This is what I saw.

—

Beth Livermore is a MFA candidate in Creative Nonfiction at Columbia University. Her work has appeared in dozens of national magazines including Smithsonian, Glamour and Travel Holiday. She lives with her family in New Jersey on a hay farm.

—

Through April 28, The Morgan Library and Museum,

225 Madison Ave, at 36th, New York, N.Y.

Hours: Tuesday through Thursday: 10:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Friday: 10:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Saturday: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Sunday: 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.