Fiction by Saadia Faruqi

—

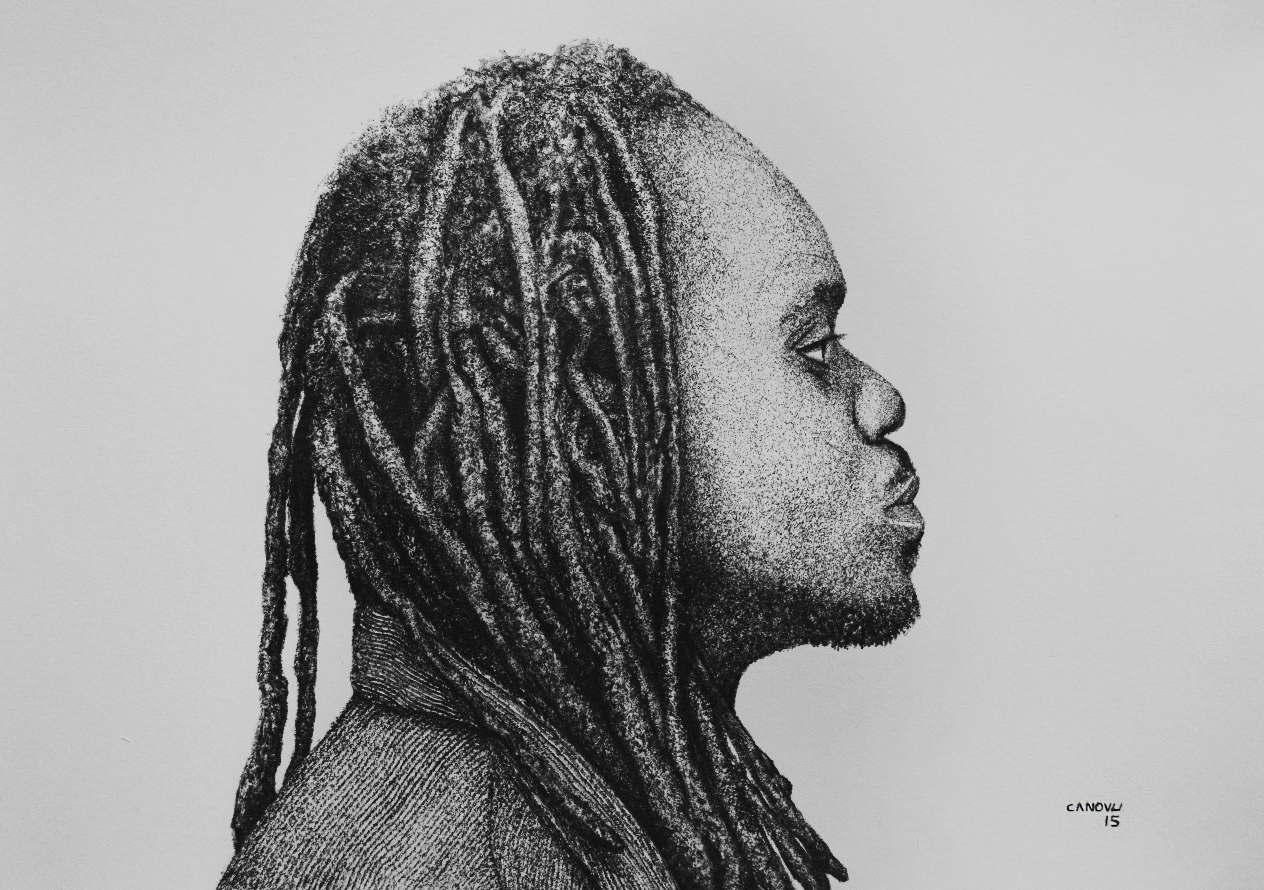

I don’t know about you, but to me, hair is the most interesting, most powerful thing in the world. No matter where a woman lives or how much money she has, her hair is her pride, her joy. Just like my hair salon, which is my pride and joy, opened after my dear husband Bilal died from a heart attack three years ago.

You may not agree with me, of course, about the power of hair. In fact, you probably wouldn’t call my shop a hair salon at all, seeing as how it’s just a room in my hut, and more a meeting place for poor Punjabi women than a fancy salon. Rarely does it actually witness a haircut, because my customers would be horrified at the thought of cutting their crowning glory. Never mind that most of my customers’ hair is mousy, withered, dry as twigs. Still, they strongly believe their husbands will stay loyal if they keep their hair long and supposedly shiny, and who will argue with age-old conventional wisdom? My scissors are resigned to a back drawer in an ancient armoire that I received from Bilal’s mother on my wedding day. Mostly I provide massage services to new mothers, application of hair oil or henna to those getting on in age, and even the occasional arm and leg waxing for village brides.

But yesterday was different, invigorating, game-changing. Yesterday turned out to be quite a busy day at my tiny hair salon, even though the weather outside was sweltering hot and I hadn’t expected anybody to visit me. My anticipation of a quiet afternoon with my Urdu digest and a tall glass of lassi was shattered with the arrival of Uzma, a thin, middle-aged woman from the other side of the village who frequented my salon almost every month for henna and chai. Today, however, Uzma wasn’t alone and didn’t look in the mood for a piping hot cup of tea. I was curious, firstly at her uncharacteristic expression of rage and secondly with the slight girl she was literally dragging like a police sergeant behind her. What on earth was going on, I wondered, putting down my glass of lassi carefully and standing up slowly to greet my unwanted visitors. I am past my prime and have gained more than a little weight after Bilal passed away, and this kind of unexpected arrival makes my heart pound in a decidedly unpleasant way.

“Uzma, what’s going on? Who is this?”

I didn’t think the anger on her face could get any fiercer, but I was wrong. Her features were distorted and flecks of spit lined her mouth like little dancing devils. She shoved the girl onto the charpai in the corner and told me: “Shave all her hair off, even her eyebrows! Right now!”

Immediately and instinctively, I knew the whole story. Shaving off the precious, shiny hair of a young woman was only a sign of one thing, meant to shame not only her but the entire family. But she looked so young, couldn’t have been more than thirteen or fourteen. She would be traumatized if I did what her mother asked.

Of course I was assuming that Uzma was her mother. It could really be anyone in the village, feeling a sense of holy indignation at the thought of a young girl committing such a big sin, one that they all imagined but never committed themselves. The village was one big family, splitting at the seams, hating each other, resigned to be chained together forever. I took one look at the figure cowering in the corner on my charpai and made a momentous decision very unlike me. I decided to help her escape her fate. She didn’t deserve being shaven and paraded through the village for everyone to laugh and point at, no matter what she had done.

Uzma, of course, wouldn’t take kindly to my magnanimity, and therefore had to be distracted. Luckily, I wouldn’t have to lie, which I hated. “Uzma, I need a new razor, a big one. I don’t usually get requests for head shavings, you know.” I had to get her out of my salon, and this was the perfect excuse. Our sole grocery store was on the other side of the village, a walk that would take at least twenty minutes in this sweltering heat. I sweetened the pot by waving a wad of rupees in front of her face. It was my hard earned money, but I was willing to sacrifice it for my forthcoming heroic act. Reluctantly, Uzma walked out, throwing threatening glances at the girl as she left. Her departure left my hut heavenly quiet again, for which I was grateful. I needed a quiet, calm look on my face as I approached the sniveling mess in the corner.

Her clothes were torn and muddied, her dupatta was clenched in one hand in defiance instead of draping over her head and shoulders in the customary signal of propriety. “What’s your name, daughter?” I asked gently, if a little impatiently, trying to suppress my curiosity. My mind was working overtime imagining the behavior that had gotten Uzma in such a tizzy.

“Zahida.” Her voice was low; obviously there was no reason to trust the woman hired to shave her head.

“Okay Zahida, no need to be unfriendly. I’m going to try and help you.” She didn’t believe me but I went on, ignoring her incredulous look. Her manner wasn’t as docile as it had been in Uzma’s presence, which proved that the older woman was indeed her mother. Who else but a family matriarch could have the power to control a girl’s expressions as if they could be wiped off the face at will?

I sighed, wondering what I had gotten myself into. Bilal had always warned me against opening this shop. “Sooner or later,” he’d say, shaking his head, “you will become a part of the lives of the women who come here.” How right he was; how much I missed him. Well, now that it seemed his prophecy had come true, there was nothing else to do but follow my gut and make the best of a bad situation. My day had started out with a promise of boring solitude, but this girl was going to make my day even better: I was going to be a heroine in her eyes. I would be the fairy princess and save her from the clutches of her evil mother.

But first, I realized, I had to knock some sense into her before she left, so that she wouldn’t be dragged back into my salon a month later for the same infraction, or worse. “You know what you did was wrong, don’t you?” I tried to look shocked, as if I myself hadn’t known Bilal before I married him. But that was twenty years ago in the city, and this was now, a different time and place. “It’s a sin to have relations with a boy, and the punishment of the village is being shaved. You know that, don’t you?”

She stared at me with big eyes. “I didn’t do anything wrong. He didn’t even touch me. He was just telling me a joke and I was laughing.”

A joke, was she serious? I resisted the urge to tell her that I wasn’t born yesterday, primarily since she could see that fact for herself. I ignored her interruption and went on. “That’s enough for our village. That’s how things start, and before you know it, you’re committing a real sin.” I made my face as stern as I could – with a round face and overweight body resulting from years of delicious, starchy foods, I doubt if I could ever look as frightening as Uzma, but I had to try. This girl needed to be sufficiently scared so that she would never go against the traditions of the village again. So that she would never bother me again.

“You should be grateful you are still alive. Two villages to the north they killed a girl who went out alone with a boy.” I shook her bony shoulders to make my point. “There is no mercy for those who break our village traditions. You must understand this if you want to be saved.”

Zahida nodded vigorously. “Yes, I understand. I won’t go near that boy again. Not any boy! Please don’t shave my head. Everyone is going to know what happened if you shave my head!” Her pleading was funny in a sad sort of way. In literature they call it irony, but that would be lost on the ignorant inhabitants of this village. Think about it, the same hair that was the beauty of these women was also a source of shame if taken away. More than actual morals or actions, it was the hair that gave and took all. I realized then what power I had in this salon. With a few motions of my dimpled hand holding a razor I could give honor or take it away. I was more than the heroine, I was a god.

I stood up regally and strode with a new vigor to the door, flinging it wide open as befitting my status. “Go, before your mother comes back. Run to the next village and never return.” Zahida’s shock at this freedom couldn’t be more obvious. The eyebrows that had seemed destined to obliteration were fixed high up on her forehead as she registered the fact that I was banishing her from her home. She had to decide, was exile a more suitable punishment than a naked head? Was a joke a serious enough punishment for either? Nobody knew the answer to such existentialist questions. The decision had to be made now, before Uzma came back.

I have to admire Zahida, she is brave even at this tender age. She stood up in one movement; with shaking fingers she smoothed out her dupatta and draped it over her head and shoulders. Instantly she looked modest, chaste, unable to sin. How well our clothes hide our faults, I couldn’t help but think poetically, whether the fault is overeating or laughing with a boy. Maybe clothes are as intriguing as hair, but not quite.

“Thank you,” she offered in a low voice, still not sure if she had won or lost. “I have an aunt who lives about fifty kilometers away. I will go there.” Did she want me to look pleased? I am sure she will find a boy to tell her jokes in her aunt’s village as well. Still, I had served my brand of justice, and I was suddenly eager to get rid of her and return to my digest stories. I watched her step outside and disappear in the rising heat of the midday sun, then closed the door quietly behind her. Out of sight, out of mind. Let the aunt’s village take care of this now.

I decided to close the shop for the rest of the day. I would make myself another glass of cool lassi and wait for Uzma to return with the razor. Her anger no longer intimidated me, for I was heroine, judge, jury and god, all rolled into one round package. No one would dare question me or my razor.

—

Saadia Faruqi is a Pakistani American writer of fiction and nonfiction, focusing on the Muslim/Pakistani/immigrant experience in her writing. She is editor-in-chief of Blue Minaret, a new literary journal, and editor of the Interfaith Houston blog. Her short story collection “Brick Walls: Tales of Hope & Courage from Pakistan” will be published in summer of 2015.