Review by Lilly O’Donnell

—

By naming his collection of short stories after one of the seminal philosophical texts of the last two thousand years, Gabriel Blackwell set the bar so high you’d need a telescope to see it.

In the original Critique of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant sought to determine how much is knowable through reason alone, divorced from the evidence of past experience. He challenged the very idea of a priori knowledge, or what we think we already know, arguing that just because something happens the same way ten thousand times doesn’t mean it will necessarily happen the same way the ten-thousand-and-first time.

In this collection, Blackwell sets out to follow Kant’s logic to its literary conclusion. He reduces his stories to their most essential, knowable levels. By stripping them of the details that authors usually use to telegraph meaning through shared experience, accepted symbols or cultural/literary references, Blackwell forces readers to approach the page without any a priori conceptions. He tells a love story as a math problem, reduces an account of torture to a transcript, a play to a list of characters and their motivations. By silencing the static of literary tropes, characters or story lines that might remind readers of other things they’ve read and therefore set up expectations, Blackwell attempts to challenge the way we read a story in the same way Kant challenged the way we perceive the world, the number of assumptions we bring to any experience.

The philoso-literary experiment of Blackwell’s collection was most successful in a piece that consists of a description of a photograph that’s never shown. The description is meticulously, obsessively detailed, but is also convoluted and seems to contradict itself. Following along becomes a mental exercise for the reader trying to conjure a clear image of the photograph, and since the description meanders and doubles back on itself, the reader can’t skip ahead and fill in the blanks but has to build the image step by step along with the writing. It makes the reader slow down and think about their own reading, the conclusions they’re drawing and assumptions they’re making along the way.

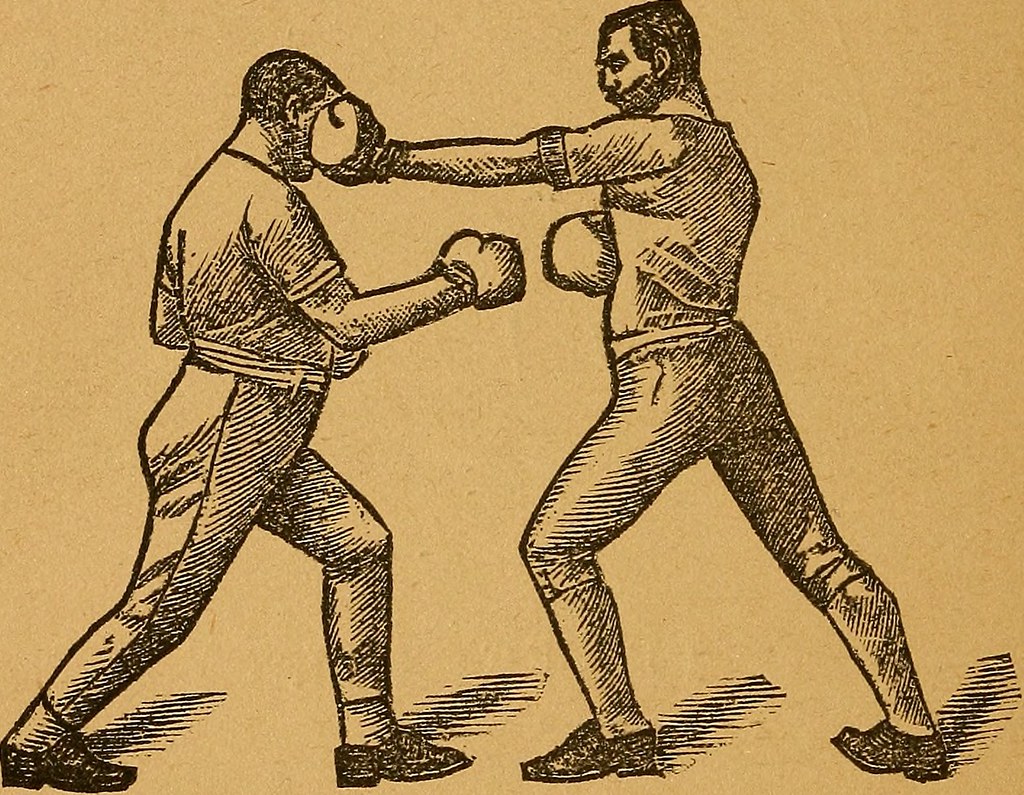

Telling stories from a remove, through documents or notations, has the potential to abstract the subjects in a way that could make them clearer. It’s like the classic art class assignment of turning an image upside down to copy it, so that rather than drawing your a priori, preconceived concept of a face or a tree, you draw the shapes as you actually see them.

That clever extension of Kant’s philosophical principle seems to be at the heart of this collection, and it’s an admirable undertaking, but Blackwell doesn’t quite accomplish the mind-bending, a priori knowledge-challenging affect he seems to be going for. Somewhere along the way Blackwell loses sight of the great potential of his premise to serve as a foundation for great writing, and gets distracted playing with the device itself. In a way, Critique of Pure Reason reads more like a series of experiments, a book of templates for cheeky ways to tell stories, than like an actual collection of complete, finished stories.

Instead of serving as a starting point for the work, the clever idea is presented unadorned, as if its presence is enough to inspire adoration, rather like a date stripping naked upon entering your apartment without waiting for lights to be dimmed and wine to be poured.

These stories might have worked better if served up one at a time rather than together in a collection—there’s a fine line between cohesiveness and redundancy. Once the reader has figured out the game that Blackwell is playing they’re left wondering what more there is. The literary extension of Kant is fascinating, bold and clever in each story, but when they’re read one after another the luster fades with each new installment so that even a reader who’s excited and inspired during the first piece is likely to be frustrated and bored by the last, wondering why the same note is being played yet again, that sky-high bar still far out of sight.

—

Lilly O’Donnell is a freelance writer and a Girls Write Now mentor. She’s currently working on her first book, a work of personal nonfiction.