When it came to disguising my emotions, I was more capable than the average twelve year-old. That was what I figured and there was proof I figured right. The kids I grew up with often said my thick spectacles and curly mop-hair obscured my expression: when I didn’t open my mouth, it was hard to know how I felt. Cookie’s and my nine months with Pops was recent history, and we were back at the orphanage. It was there at the orphanage, Junior Village, during the spring of 1969, that my favorite comic book, The Amazing Spider-Man, was snatched from me and ripped apart.

My latest comic books had not come easy. I had begged and traded, acquiring one twelve-cent funny book at a time until they could be alphabetized by title or sorted by issue or publisher or superhero and, when placed one atop the other, make a substantial enough stack to be considered a collection.

I was walking and reading when it happened. With a crease in my voice, I asked the kid,

“Why’d you do that?!”

“What you gonna do about it?” he shot back. Setting a look of implacability on my face, I turned and walked away.

That night I carried my short stack of comics and a few library-lifted books from T. Roosevelt Cottage onto the single street that curled like a noodle through Junior Village. Past the high-steepled chapel and the three-story cottages of Taft and Harding and Coolidge I walked, down past the Dining Hall and Admissions-Infirmary Building. Where the street flattened out, I waded into the woods that covered the valley, which held Junior Village like a fist. Beneath a kaleidoscope of starlight, I slid my box of books under a flowering shrub.

Not three months later—in August of ‘69, the day after my thirteenth birthday—I stood hunched in the doorway of the McKinley Cottage lavatory staring, owl-eyed, as one boy fellated another. The fellater was the bully who had snatched and ripped my Amazing Spider-Man.

My cranium clung to the details: the backed-up-toilet aroma of the room; the jeers of the tangle of teens ricocheting off gritty tile; the bully kneeling in the doorless stall, dungareed legs splayed wide, tee-shirted back, muscular and spotted with sweat, bobbing, between two sooty knees.

Where are the counselors? I wondered. And Why did this bully transform? You wouldn’t have known it to look at me, but I wanted to cry. It was my pragmatic self who tapped me on the shoulder and said, You’re watching an initiation. The bully had turned thirteen days before me. He had been transferred from T. Roosevelt to McKinley, “The big boy’s cottage,” the day after his birthday, as had I. Be prepared, my pragmatic self warned. It’ll be your turn next.

~

It must have been ninety degrees the September day of ’69 that I sat waiting on the hard bench in the marble hall outside of the DC Superior Court courtroom. Ms. Shickles, my latest social worker, had promised I’d meet her replacement this day. Cookie and Mama were in the courtroom testifying in that same rape trial against my father when a guy strolled up wearing a squeezed-out smile. He looked sophisticated, and scared.

“You must be Nick.” When I nodded, “I’m Scott Surrey, your new social worker. But call me Scott.”

“How ‘bout I call you Mr. Surrey?”

“How’re you handling all this?” scared-looking Mr. Surrey asked, still Cheshire-grinning. “The trial? Junior Village?”

“I’m cool.”

“And Saint Anselm’s Abbey?”

“It’s awright.”

“Awright” meaning I would not discuss the squandering of my academic scholarship: that this school, too, had become bleak (because I saw in the students’ eyes that I was impoverished, that they found it funny and elbowed each other), which, somehow, translated to boring (and what incapacity I, as a boy, had for boredom); how I’d begun failing Latin and eighth-grade algebra; that I was finding myself on the receiving end of paddlings by the Benedictine monks for strong-arming the lunches of those apparently rich Caucasian kids. Because one had to be hard back then, and I could not be hard at Junior Village.

Since I suspected it was only a matter of time before I was expelled, I changed the subject: “Been on vacation?”

“How’d you know?”

How could I not have noticed his tan? As I could not but notice that Mr. Surrey’s shoulder-length blond hair and blue eyes were offset by an odd double-snort as he spoke, like a mare fighting the rein. It also seemed odd that, at twenty-four, he had only just graduated from college, and that this was the first month of his first job, ever.

He volunteered, “Just got back from Saint Croix. It’s part of the Virgin Islands.”

“See any coral?”

“You know it.”

“Did y’know that coral is little animals that eat meat?”

“You’re plenty smart for a thirteen year-old, aren’t you, Nick?”

“I read a lot.”

“What are you going to do with all that brainpower when you grow up?”

“Go to Harvard Law School,” I snapped.

Typical was the belief that Junior Village kids grew up to be crooks and junkies. I was set on something else. During my father’s trial, I had discovered that lawyers were ennobled with authority and, by the likes of their fancy clothing and lingo, money and a good education. A black Perry Mason is how I imagined my adult self: suave, rich, and beneficent. I knew Harvard was number one.

I might say that I aspired to Harvard because acceptance there would mean I’d made it. But, truthfully, I was just “signifying.” School had always been, would always be boring. “Signifying” as such made the vibrant world seem within reach.

“Harvard works,” said Mr. Surrey, grin working overtime, “My dad teaches at Harvard Law.”

Mr. Surrey, I would discover, was the only adopted child of Stanley and Dorothy Surrey. Stanley Sterling Surrey, an accomplished attorney, had spent the last eight years leading the Kennedy and Johnson administrations’ tax policy offices before resuming his professorship at Harvard.

“Get out’a hea’!” I shouted, reserve forgotten. The world, abruptly manifested; school as an escape vehicle! I decided right then that Mr. Surrey could be an unlikely ticket out of Junior Village. But I needed to work him fast, before he quit, as had every one of my previous social workers. Resuming my air of indifference, I asked, “Think your dad could get me in?”

All that (being a fanciful notion) did not work out as planned. Weeks after meeting Mr. Surrey—from the sea of my yearning, it seemed—a mysterious woman entered my life. It was she, not Mr. Surrey, who would deliver me from that place where bullies could be victims.

My future benefactor – I’ll call her Miss Smith – had, apparently, been watching me from her living room window. She’d witnessed my descent from the DC Transit bus, my trudge past her house in Saint Anselm Abbey’s Boy Scoutish uniform. It would have been easy enough for her to inquire at the Abbey, to learn I was a ward of the DC government.

She greeted me from her stoop one crisp November morning, “You’re Nick, aren’t you?” A taut, mid-forty-ish, brown-skinned woman with the air of a Mother Superior, Miss Smith wore no perfume, makeup, or jewelry. Her hair was hot-ironed straight and cut, medieval monk-like, above the ears. In a round-voweled voice, she asked, “Would you care for a cup of hot chocolate?”

That detour to Miss Smith’s for cocoa and a chat became a routine I grew to adore. There was only a single spark of misunderstanding during our bright beginning: When she learned I had a sister for whom I felt responsible, she chuckled—J. Edgar Hoover peepers peering over cat-eyed bifocals perched on the tip of her prizefighter’s nose—“That’s unfortunate, isn’t it?” Suspecting her quip was at Cookie’s expense, I frowned. But watching her amusement, I began chuckling along with her, and her laughter became a part of mine. When Miss Smith brought up the possibility of a trial adoption, I barely wondered, Why me? What I thought was, She is a way out. I said to her “Cookie goes where I go.”

Both Ms. Shickles and Mr. Surrey expressed doubts about Miss Smith. According to Ms. Shickles’ report, which Mr. Surrey shared with me, “The applicant is unmarried, does not like girls, and has lost some interest in Nick since he was expelled from Saint Anselm’s.” Mr. Surrey said, “I want the best for you. I’m just not sure she’s it.”

Well, I was sure.

The sweet spot for selection into DC’s temporary home placement program, Foster Care, was between the ages of post-toddler (when independence began to bud) and pre-pubescence (before the vines of sexuality took to creeping). I was years beyond the ideal candidate, I knew. So, I stood my ground. With no other placement options, and given the discontents of their offices, my two social workers must have convinced themselves that most any place was better for me than Junior Village.

Miss Smith’s three-bedroom single-family was at the corner of 12th Place and Varnum Street northeast, a neighborhood gripped by Providence Hospital on the west, Saint Anselm’s Abbey to the east, Catholic University at the south, and, to the north and directly across the street, The Josephite Rectory. I shared a bunk bed with Glenn, her nephew, a reserved boy a year older than me, and singularly focused on the build-it-yourself Mustangs and Corvettes, Zeroes and Messershmitts that adorned his room. Cookie bunked with Glenn’s sister, Sheila, a chunky girl her age with an indolent demeanor. We never got to the bottom of their not-nuclear-family mystery. Miss Smith met any mention of Glenn and Sheila’s absent parents with “We won’t be discussing that in this house.” She enrolled us at Birtie Backus, the middle school at which she taught.

Have I mentioned that Miss Smith had never married? She had no significant other. It was also true that she did not like girls, particularly girls turned sullen by a history that had nothing whatsoever to do with her. As I tended to my studies, Cookie got stuck with the chores. When Cookie complained, I countered, “You wanna go back to Junior Village?” Her response: “The only reason I’m here is you.”

In the year since our father’s arrest, Cookie had changed. Karen, her Christian name, was what she demanded her new friends call her. She’d grown independent, tough, even. She had also begun to consider me, the least courageous of brothers, an embarrassment.

When I summon forth the kid I was at thirteen and give him the third degree, “Being light-skinned was hazardous duty at Junior Village,” is his response. And it was certain that my mixed-raced sister and I were a mishmash. Ten year-old Cookie was a milk-faced tomboy. By eleven she was a pallid girl-Kato, punching anyone who looked at her twice (That was the way of Junior Village, you couldn’t walk and look at someone. Looking would get you beat up.). Fighting earned her the respect all Junior Village kids craved.

The boy I see when I look in the rear view mirror confesses to putting his forcefield up, to cloaking his difference by reading and slipping into the state of Staying Out of Harm’s Way. This point of suspension grew until he/I understood little else except the desire to avoid trouble. I also feigned not noticing Karen-not-Cookie’s new disdain. How could I blame her? I thought myself a coward, responsible for my sister’s rape by my father. If you’d asked me then, our dad had slapped and bludgeoned cowardice into me. Still, it hurt that my sister who once looked up to me no longer did.

Karen saw Miss Smith as one of the many Foster Care creeps we had learned to avoid over our years at the orphanage: professional parenters trolling for children and the government checks that trailed them. Karen only agreed to our placement because I wanted it so badly. She told me as much. She also opined that I’d developed an infatuation for Miss Smith. “You so far up ‘er butt, she can’t take a crap” is the way she put it.

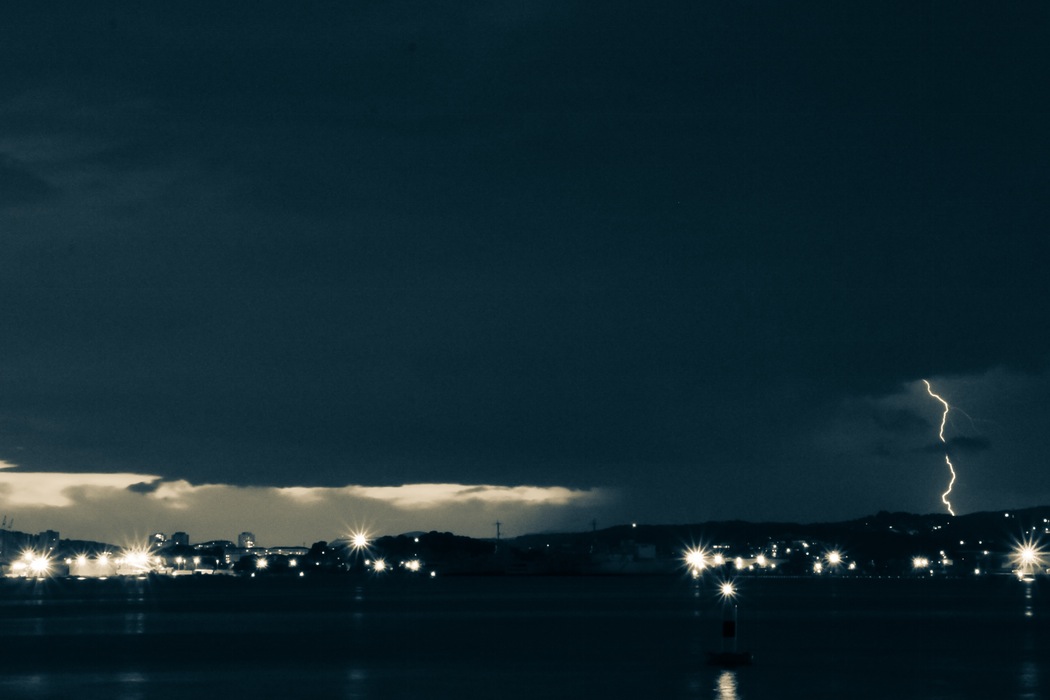

Chapter Break – Sample Photographs

Ms. Smith was a sorceress.

What I remember developing between Ms. Smith and me began one night shortly after we moved in. Glenn and I were lying in our bunks going over the events of the day when Miss Smith called, “Nicky, come here.” When I shuffled into her bedroom, puzzled, “There’s no talking in this house after we retire for the evening. You’ll sleep tonight with me.”

“What about Glenn? He was talkin’ too!”

Miss Smith, giving me the deadeye, patted the mattress. I clambered into her four-poster wearing what I always slept in – white cotton briefs. Within minutes her breathing settled into a regular cadence. I tried to settle in, too.

I was awakened by Miss Smith’s hand brushing my back. When I looked over she was fast asleep. A short time later, I was roused by some soft part of her coming to rest against me. I lay embarrassed but excited until the intermittent cars in the street began to roar like lions and the rhythm of her breathing, regular as raindrops, coaxed me back to sleep. I awoke the next morning with my usual A.M. hard-on. Miss Smith was already up and at ‘em. Not a word was said by anyone about where I’d slept.

At least one night every few weeks something similar happened. As bedtime approached, Miss Smith would find some fault. I would be summoned to her bed where parts of her would inevitably settle against parts of me. During the day-afters, no one made mention of our sleeping together. Even Karen seemed oblivious.

I began looking forward to nights with Miss Smith. I’d come to believe that her slumberous touches were purposeful. Foster-home shenanigans were urban legend at Junior Village. Since the age of nearly 12, I myself had learned – by this way and that – of Foster Dads (as well as our natural father) trying to touch Karen. Mr. Surrey had expressed concern that “Something’s not right with Miss Smith.” The not-right, I figured, was her liking me in some similar but better way.

Like many boys, I’d begun masturbating as a pre-teen. During the months sharing Miss Smith’s bed, I beat off con brio (with perseverance, with abandon and immodesty): before arising from bedding suffused with her, in the prickly school cloakroom, during my toilet at night. I tried to bring my longing to Miss Smith’s attention. She refused to acknowledge my tented briefs, my vigorous chunks of bathroom time.

By springtime, my nighttime desire had wandered into afternoons of an effulgent Miss Smith transformed by the translucent cotton nightshifts into which she changed after school. I was tormented by hints of her nakedness: her prominent papillae, the shadowy isosceles at the confluence of her thighs. During one postprandial study session, nodding towards a nude-under-nightshift Miss Smith, I whispered to Karen, “Not bad for forty-sompin’.” Eyes widening, Karen whispered back, “Eeuwww, you like Old Raisin Tits?”

I never again broached the subject. But it was during this time that I began to return Miss Smith’s nighttime touches: my fingers brushing her shoulder, my foot on hers. She never awoke, never protested. I grew bolder: my hand at her hip, thigh, until an apparently still sleeping Miss Smith turned. I persisted. She turned again. By morning I was a wreck. She seemed rested and ready for the day.

As my longing for Miss Smith concreted, interest in girls my age waned. After a day of touch football, a Saturday night of slow dancing, I raced home, anticipating, “Nicky, you’ll sleep with me.” But though she sometimes summoned me, frequently she did not. I felt bedeviled, stymied by her, like a middle-school dropout presented an algebraic proof. Then came the incident that cut through the springtime anesthesia.

We were alone in the house the afternoon Miss Smith asked, “Nicky, would you like to watch a little television?” Then, “It’s cooler down in the den.”

The closed-shut basement door sealed me in with her. She had not seemed drowsy. But she unfolded the pullout then fell past me into an apparently deep sleep. She lay in a curl facing away, nightshift straining against her back and across the swell of her buttocks. Hot excitement poured into my brain. She’s got to be faking, is what I thought—Her persistent summons, our nightlong episodes of touch-and-turn, I could not interpret her repose as anything but an invitation.

She was naked, as usual, under the thin cotton shift. Heart slamming, I unzipped my dungarees then inched forward, caterpillar-like. When my body touched hers, I stopped and held my breath. I wanted to lift her flowered nightdress, but dared not.

She lay silent, breathing deeply.

I began to move my hips, rub my ornament against her nightshift-over-skin. I could barely feel the zippered teeth scraping my flesh. It was the tingle I felt. A tingle that swelled then exploded onto flowered cotton.

My ragged breathing ripped the still air. The room was a tomb. How humiliating! Confusion is what I felt: Had I mistaken her repose for invitation? Then shame: If I’d thought she’d acted with intent, why not somehow bring it up? Why not ask? What kind of man was I?

I began to work my way back across the tarpaulin-like foldout. Hot-faced, I stood. When she didn’t stir, I beat a hot retreat up the creaking wooden staircase.

Weeks after, I was sitting in class in a near-catatonic swivit doodling “V Smith,” not comprehending the helplessness I felt, when I was interrupted by the call to recess. The playground was where I heard three young Tarzans beating their bony chests and yodeling feats of conquests, a shimmering huddle of boys I hardly knew:

First boy: “I heard she fuckin’.”

Second boy: “Fuckin’?”

First boy: “Miss Smith, eighth grade. I heard Reds boned her.”

Third boy: “Oh, I hit dat, too.”

First boy: “You? Pu-lease.”

Third boy: “Don’t believe me? Listen in when I talk to ‘er!”

First boy: “I wouldn’t fuck her with yur dick.”

Second boy: “Niggah, don’ you know old bitches like that give you worms?”

Third boy: “Bend over n’ I’ll feed yur ass some worms.”

But it was when the first boy jeered, “Bet you in love now!” that the three folded over in laughter: they knew love was not part of the game. Any boy who developed feelings for a female was pussy whipped, an automatic loser.

Today, I give little credence to schoolyard braggadocio. Back then, because I was young and she, not the kind of woman about whom boys preened and gossiped, I concluded those boys were speaking truth. I had assumed that goodness lived within Miss Smith, because she’d rescued me from Junior Village, because she held a position of authority. I had to admit, because I was devastated, that I had come to care for her. Paradoxically, I, who had not consummated my desire for Miss Smith, was one of the pussy-whipped.

I dared not confront her about what I’d overheard. Who was I to broach with Miss Smith a subject so intimate as sex? But the next time Karen complained, “I can’t stand ‘er snooty ass!” I concurred: “She a bitch.”

“Your saint, Miss Smith?”

“She always workin’ you like a maid.”

“Like you just noticin’,” the words slanted from Karen’s mouth. When I slung my arm around her shoulders, she shrugged it off. “Whatever she did, it must be bad,” Karen said, looking at me sideways, “‘cause you trippin’.”

Was I tripping? I did feel betrayed by Miss Smith. Running events backward in my mind, I felt she was no benefactress. It was Miss Smith who had plotted my seduction, then expecting me to emerge from her ministrations a young Tarzan thumping his breast. Her circumspection I attributed to caution. She was, after all, my foster mother.

In my anger everyone was complicit. I felt betrayed by Glenn, her nephew: they must’ve slept together. What other explanation was there for his non-reaction to my nights in her bed? I resented the schoolboys for revealing Miss Smith’s liaisons. I detested the bullies at Junior Village for harassing me to the point of ineffectualness; my father for my spinelessness, the counselors and psychiatrists for overlooking my abuse.

What I said was, “It ain’ just Miss Smith, they all fucked up. Lookit what happened when Junior Village sent us to live with Dad—he messed with you, and the judge found him not guilty!”

Karen’s raised eyebrows told me that I was ranting. “Nicky, what’s wrong?”

“I’m just sayin’,” I said, hiding behind my lenses, “somebody should’a said sompin’ before sendin’ us here.”

“Well, I said sompin’,” Karen recalled. “Mr. Surrey and Ms. Shickles said sompin’, too.”

But, Karen reminding me of my poor judgment only angered me more. The social workers recognized her type. And they still approved her application!

Karen asked, “Did Miss Smith do sompin’?”

“Naw. She didn’ do nothin’.” As far as I knew, I was telling the truth. My speculation about what Miss Smith might have done was just that. But I had done to her whatever I could get away with (to the extent to which I was capable). Who had been wronged, me or Miss Smith?

If I seem equivocal, it’s because I was, and am. It is not sufficient to say that I did not then think of Miss Smith as an abuser. The child that I was felt confused, compliant, enticed. If told, I might have accepted that reports of female sex offenders are met with disbelief, and that they rarely enter the legal system. It is not sufficient to say that I would not have guessed that women commit one-quarter of all child sexual abuse; as I could not have imagined the nuances of pedophilia: that offenders do not have to penetrate or be penetrated, that women interested in sex with young boys often practice a pathology of seduction and misdirection, ironically called “The Mrs. Robinson approach” (after a character in 1967’s The Graduate). I can say that I knew instinctually that boy victims were taken less seriously, because of the assumption-myth that to be seduced by a woman is every little boy’s dream-come-true.

Still, today, I want to rush to Miss Smith’s rescue; shield her from my conclusions; represent what she might offer in her defense (because, to my knowledge, no exegesis exists of her but this one). But she, I believe, would not deign to defend herself. And living as we did in our bog of silence, the only thing I can say with certainty is that I will never, truly, know her intent.

I do know I was lucky I was young. Over my heartache, my cells were already forming a scab. Even as I was mending, I was imagining a time when I felt nothing for Miss Smith.

The months flew by. Nothing changed. By the close of May 1970, as summer was about to breathe its fiery breath over DC, Karen revealed to me her intention to return to Junior Village. What she whispered was, “So sick of ‘er. I’m out’a here!” I felt punched in the gut. Karen’s decision squeezed me into a domestic cataclysm: forced to choose between Miss Smith and living as close to a quotidian existence as a kid like me could expect, or my only sister and life at Junior Village.

When I built up the nerve to tell Miss Smith, “Me and Karen goin’ back to Junior Village,” she froze, J. Edgar Hoover peepers reconnoitering my face for a hint of the rupture between us. In her round-voweled voice, she urged me to “Let Karen go, and I’ll forget you ever wanted to leave,” as if this was an offer too good to refuse. She did not touch me as she spoke, though my eyes whispered how much I wanted her to. It sounds fatuous now, but I hoped she would not only embrace me, but confess her romantic love. I hoped she would say she’d concealed her affections because of the legal consequences, then beg me to stay.

Yes, I was still under her spell. But no confession forthcoming, with marble lips, I threw at her, “We goin’.” Those two words were worse than weeping.

It was closing in on the middle of 1970 the heat-hazed day Karen and I walked out of Miss Smith’s ambit—yet another Family Walk of sorts. I was not yet fourteen. Yawing towards Mr. Surrey’s blue Barracuda idling at the curb, I glanced back at her thin form radiating in the doorway. On occasion, I think of Miss Smith: her dry, tree-bark smell; how I’d tried to peel back the layers, but never got close to her core.

“The Sweet Spot” by N.R. Robinson is a Nonfiction Finalist in Columbia Journal’s 2019 Fall Contest, judged by Emily Bernard.