High Noon / Rio Bravo

The Western is one of the three American political landscape genres (the other two are twins: the crime saga and the noir detective piece). The Western is the Odyssey that trails the Iliad of the Civil War.

Over Thanksgiving, I watched two well-loved Westerns that actively tried to tie the Western to the contemporary politics of the period in which they were made: High Noon and Rio Bravo. These two films make for good grist to discuss art, the role of art as historical processing, and the role of the Western as American epic.

Both films were made during the Blacklist/Joe McCarthy fuck-up in the fifties. One a deeply enraged screed against group cowardice, the other a call for individual skill and reluctant cooperation—the American dream, basically.

High Noon was specifically made to scorn the politics of the 50’s, and it does so, capturing with detail and clarity how the long standing wants of the many—the white many—overpower what is right with a ticking clock, airtight plot.

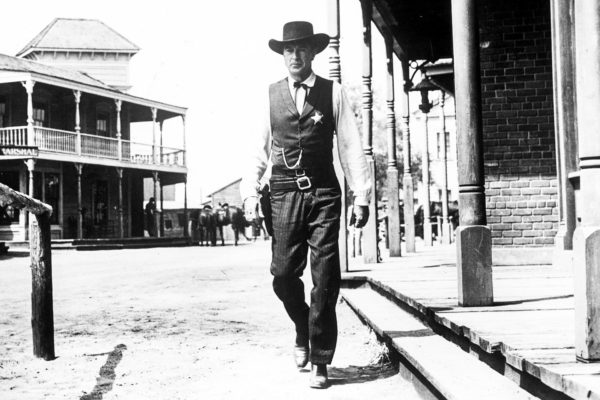

The great Gary Cooper plays Will Kane who, as the film opens, is getting married to Grace Kelly’s Amy Fowler. All the potentates of the town are present because Kane is the Marshall that has cleaned up the place. So the mayor, the previous Marshall, the town judge, and the town lawyer (though pointedly not the town preacher), all see the Kanes’ hitching. But. Over the opening credits we have seen three unspeaking desperadoes riding into town, and just as the ceremony finishes, we see them walk up to the train station ticket window and ask about “Frank Miller.” The name inspires fear. The train station master, sweating bullets, races to the Marshall’s office where he finds Kane leaving. It turns out Miller is the dastardly villain that Kane had sent up the river years ago, and now he’s out and coming back for revenge. Everyone, including Amy, the new Mrs. Kane, urges Will to run. And, for a moment, he does. He tries to ride off with Amy. But he must turn back.

The next hour of the movie consists of Will going to everyone in town for help and getting turned down. The film shows how each form of commerce arrays against Kane and the rule of law: The saloon keeper liked the lawlessness that kept the saloon packed when the outlaws ruled; the hotelier liked how many people were always in his hotel when the criminals were in town; and even the mayor, who respects Cooper, wants him to go away, lest a gun fight sully the town’s reputation with the powers that be up north. Even his new wife, a pacifist Quaker, denounces his intention and profession despite their mutual love. Literally everyone abandons Will except for a scrawny kid and a drunkard with one eye and a limp, both of whom Kane gently refuses.

Right on the hour, Miller comes into town. Amy has since met Kane’s former lover (and Miller’s lover before Kane) Helen Ramirez, who is leaving town on the train Miller rides in on, and Amy, to rebuke Kane, almost goes with her, but when she hears the first gunshot she runs to save Kane. A very tense shootout involving fire, horses, and mirrors ensues. Finally, Amy sacrifices much of her morality by shooting one of the hoodlums in the back, allowing Kane to kill Miller. The final shot of the film is of Kane throwing his tin star in the dust.

Every second of High Noon brims with tension and real anxiety for Will and Amy. The countdown sounds like a narrative gimmick, but it works absolutely because everything is focused on turning the screws on the characters, not create unnecessary complications for no reason.

Rio Bravo was made in response to High Noon. Both Wayne and Hawks felt that High Noon was un-American. Wayne was particularly against it as being anti-American, while Hawks seemed mostly to be mad that Cooper’s character is “not a good lawman” who gets “saved by his Quaker wife.” As a result, Rio Bravo is stuffed to the brim with people offering Wayne’s Sheriff Chance help—which he continually refuses. Every character that offers Cooper’s Kane aid in High Noon is mirrored in Rio Bravo: the crippled old man, the drunk, the overconfident kid, but, instead of being treated with tender-hearted realism like High Noon, they are all turned into bona-fide heroes. The weak fourteen-year-old in High Noon becomes the great seventeen-year-old Colorado Kid who is as good with a guitar as he is with a gun!

Rio Bravo’s plot is this: John T. Chance (John Wayne) who must defend his town of Rio Bravo from the threat of Nathan Burdett, a wealthy cattleman intent on getting his brother out of the town jail. See, Chance has a drunken deputy “Dude” (played by crooner Dean Martin doing good work) who, in the first scene of the film, just gets back from a “2-year drunk” in time to find Nathan Burdette’s outlaw brother Joe Burdette hanging in the town saloon. Dude sees Joe bring a drink to his lips and gestures for Joe to give him a drink. Joe seems to comply, bringing out a gold dollar, but instead of handing it to Dude, he throws it into a spittoon—a brass pot for tobacco spit. Dude, so degraded, kneels to put his hand in—then Sheriff Chance appears. Chance stops Dude form putting his hand in the spittoon, and Dude punches him in the face. This knocks out Chance and Dude tries to hit Joe Burdette. Burdette then kills a guy and runs to another bar where, magically, Chance has recovered, wielding a Winchester rifle, and forgiven Dude enough to have Dude help him bring in Burdette.

Once Joe Burdette, Nathan’s brother, is in jail, the movie seems to totally lack forward momentum. It is highly episodic as various people reach out to give Chance help, but Chance, of course, refuses all aid. Still, people help him. Even a very beautiful, chatty, and interesting woman who impossibly loves Chance pitches in with a flowerpot. Of course, everything ends happily after when Nathan Burdette kidnaps a cleaned-up Dude, instigating a long, entertaining gun fight where we never see the bad guys until they are defeated. There are laughs then an implied marriage.

Where High Noon is a tragedy of the first order, Rio Bravo is nothing but a long episode of Bonanza. It is a very inventive and fun episode of Bonanza, but it still watches like an early sitcom. From the first moment, we know the John Wayne’s John T. Chance can do anything; even if he didn’t get help, it wouldn’t matter. So who cares if those people want to help him— we know he’s gonna win! Howard Hawks tries hard to make this trampoline into a taut political statement about the altogether-ness of America, but he fails because there is no danger.

In terms of plot, then, I feel that High Noon is superior. Rio Bravo is loosely episodic while High Noon is taut dramatic screenwriting. Plot is not the be all and end all of filmmaking, but these are high studio system Westerns: one expects a tight plot, or the untight plot must subvert expectations or reveal something to us about the nature of plot or cinema. For example: The Searchers. That film is also episodic, but it wrestles with the very roots of our endemic American racism. Rio Bravo does not possess that level of insight. Nor does the open plot structure do much for it that I can see except make it longer. The Ricky Nelson/Dean Martin duet is nice though.

In terms of characters and character development, High Noon is pure drama—both Will Kane and his wife Amy have strong character arcs, and both undergo a huge dramatic shift. Pacifist, Quaker Amy kills someone, and Will renounces the job that was his identity. Both undergo a form of death; I would say Amy even more than Will. Both Kanes lose themselves because of the town’s abject cowardice. Certainly, these kinds of dramatic shifts are not necessary for a work to be successful, but High Noon makes these two reversals central to its political message.

The only character that has a dramatic arc in Rio Bravo is Dude. The redemptive arc of Dude is the most interesting character path in either film. He becomes human again after being nothing for a long time. Will Kane is as great as his loss, but he is a superhero, a Greek figure. Wayne’s Chance does not change at all from frame one to frame last. He is a cartoon of the perfect Lawman that Cooper is. Mrs. Ramirez (who was actually a Mexican actor who won a Golden Globe for this film) is very interesting but not given a ton of screen time. We see all of Dude’s story in the film itself—his ups and his downs. But he is relegated to second fiddle after Wayne, diluting the potency of the soul he brings to the film. If Rio Bravo wanted to really be a strong counterpoint to High Noon, I would have made Dude the Sherriff and the film about him regaining his faith and self. But nope, we get John Wayne John Wayning it up.

I also want to highlight the visual splendor of High Noon. The visual language of director Fred Zinnemann and DP Floyd Cosby is stunning. A few examples: first—a smash cut of children running out of a church to the railroad tracks that will bring the evil Miller into town, both beautifully composed. In that one cut we get two visions of the future, the positive first literally cut off by the second. Second example—a crane shot that moves from a tight close-up on Cooper’s face to a bird’s eye view of him small and alone in the town’s streets. Final example—a shot of Miller’s three goons waiting for the train is composed like a Picasso, even down to the figures extending past the frame, breaking the world.

The only technical aspect that Rio Bravo wins on is acting. Hawks knew how to direct actors in a way that Zinnemann did not, and yet the wonderful performances of Rio Bravo do not redeem the story to me (and I am an actor myself) because the nice naturalistic performances sit underutilized among the clutter. If only Dude had been at the center of the story.

So High Noon, on almost every technical front, beats Rio Bravo: Its plot is better, it is more fun to watch, the themes are reflected in the characters, the dialogue is great, and the shots convey both story and poetry. It is clearly the superior film.

And yet.

High Noon is not reflective of the real West. The real West was a collective-oriented place. A place that distrusted money and big ranchers like Rio Bravo’s villain Nathan Burdette. The West was “Won” by people of Caucasian, African, and Mexican/Spanish (that slash is super complicated but we don’t have the space here to consider the divide between indigenous Mexicans from the mixed Spanish people who mostly run the country) people working together to eradicate the native tribes of the plains and the mountains. In fact, the biggest lie that these two films tell is in the total absence of indigenous people in both. In High Noon, I concede, that there are two generalized “Indians” outside of the Saloon, but I fear they were more window dressing than actual signifiers, let alone people. So while Rio Bravo is a little beyond a fun knockabout pean to the collective American spirit—it is telling the truth about the collective American spirit that existed before World War II.

See, Hawks and Wayne, in Rio Bravo, try to revive an ideal that could not live in the fully industrialized, individualized, McCarthyized, Cold War, post-War world. In his early films like Meet John Doe and Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, ironically, Gary Cooper represented what Wayne and Hawks want to sell us on in Rio Bravo—a collectively minded community that works together to achieve a moral goal—while in High Noon Cooper allows us to watch that good man do his last altruistic deed. And John Wayne now represents the sort of empty male chauvinist power that Wayne so clearly wanted to put aside and put down for Rio Bravo.

High Noon is a mirror for us: It shows us our acceptance of criminality if it means dollars. Our cowardice and self-involvement. Our resentment of having to do the right thing since it puts us out. Rio Bravo misplaces the actually interesting character work, even though Dude opens the picture, it has no real plot; yet it actually reflects what the West was like and the sort of rag tag people that made up white/American society in the West. Rio Bravo misplaces its art because it does not understand the times that it was made, even though it more understands the times it is showing. High Noon is a great work of art because it is so indelibly of the moment it was made and saw into the future. There are no universal artistic rules, but these films do tell us something about how artists can put something together that is good but miss their own place, making their own art obsolete.

The divide between these two movies also sheds a lot of light on what happened to white men after the war—a shift we are still dealing with. When we see Jimmy Stewart or Frank Capra or John Wayne as Republicans, we think of them as post-sixties Republicans or as Red Scared republicans. However, it is more complicated for these men who actually dealt with the War. It changed them, and it changed the world in a way they were not prepared for. The idea and ideals of the America they fought for were killed by their efforts to save them. These two films show us that divide.

We are still living with the problems of High Noon and the papering over of contemporary problems with History of Rio Bravo.

The problem with needing a hero is that it means something has already gone horribly wrong. We should aim to be the community of Rio Bravo, as that is our dream, but we need to keep watching High Noon because that is both more our reality and better art.

Alex Dabertin is a first year in the Fiction concentration but he does dabble in criticism, mostly of film, and that can be found in various places: Bright Wall/Dark Room, Film School Rejects, and The Smart Set.