The Big Red One

I stepped out of the hotel where Georgia O’Keeffe lived in New York City and into the urban canyon. The blue light of the clear skies bled to gray among the buildings. The breeze blew the pom-poms and hair of the college girls, dressed in white.

Wow, they’re here to hail my departure to the airport, I thought.

I veered away and down the access ramp to the left. I looked at my watch. A dozen cheerleaders and a big brass band blocked the steps. They spilled over the sidewalk and into the street, taking over the first lane as well. A coach bus waited to deliver a sports team to their game. It was March, after all.

I asked a guy standing next to his black SUV if he was there to pick up the crew for Flight 780. He said, no, but he’d call them for me. I said I’d take care of it.

Where you flying?

Vegas, I said.

That’s a pretty good deal, he said.

I thought of the smell of cigarette smoke and desperation.

Sure is, I said.

The car was five minutes late. I clicked on my app and called the limo company.

They told me the car would be there in a few minutes. My captain was missing, too.

Never had to deal with a late captain before.

The band struck up a tune while they waited for their ball players to show. People stopped and pointed their phones at the band. I looked at my watch.

My wife brought boxes down from the attic. She put one in front of me and told me to go through it. I threw away 30-year-old owner’s manuals for lawnmowers that were long gone and entry forms for races I never even ran. I found a map with my father’s precise handwriting on it. It showed my high school cross-country ski trail. His name and two others were written next to different dots. The blue mimeographed lines on the map showed where skiers would race. I looked at the dot that symbolized my father’s spot along the race course. It was next to a trail intersection near the finish line. I looked up from the paper and remembered the lone figure of my father standing in the snow as I raced to the finish. I was always proud that my parents came to stand in the snow to cheer me on. But three decades later, I finally realized, as I held the paper, that my dad wasn’t just a spectator that day. He was a course marshal. Obviously, he could do both. When I think of that race, I think of how the racers outnumbered the spectators. And now I realize the crowd of people was even smaller than I remembered, since my dad was also part of the race staff. I got a couple handshakes. Some pats on the back. I think it was the only time my girlfriend showed up. At least one person came to see me race who wasn’t a blood relative.

That was my big day. I was the 1985 Division II New Hampshire state champion in cross-country skiing. My team was also the overall state champion. We finished by the empty, snow-covered football field in front of a dozen people, many holding clipboards and stopwatches. Eighteen out of the previous 20 years, my team was the state champion. Our coaches still had to go beg the athletic director/football coach for money to buy ski wax.

After four years of high school racing, you’d think I would’ve been done with the inferiority complex. But I wasn’t. Olympians in my sport could travel 50k in two hours. That means 15 miles per hour under your own power on skis. I helped build parade floats for a football team that played a whopping 12 minutes between hikes and downs. Whenever there was a list of the toughest sports in the world that included cross-country skiing, I would crow about it to anybody who would listen: “See? See?” My sport was tougher. My sport was worthy of more admiration. They should have a homecoming parade for me.

I held a grudge for decades. I compared the worth of the sports I did with baseball, hockey, basketball, and football. Age and time have worn me down. I realize now that these pursuits have intrinsic value to the athletes themselves, regardless of the sport. I’m even mellower about spectating. Watching cross-country skiing is not for everybody, or even most people, and that’s okay. I can even admit that I watch the Superbowl.

Something finally shifted in me last year and it was a relief. I had the simple thought that it was all just entertainment. I stopped mixing athletics with the spectacle. Suddenly, watching a football game was the same to me as going to see a concert. I still find it a little irritating when someone finds out where I live and they ask if I’m a Vikings fan. Sports fandom is both geographical and somehow mandatory. “My regional sport collective is better than your regional sport collective.” I just don’t care. I don’t begrudge people their entertainment anymore. You want to work all day and then watch football? Great. You want to work all day and then listen to Taylor Swift? Great. It’s just entertainment. Knock yourself out. Work hard, play hard.

The saying isn’t, “Play hard, work hard.” I’m dating myself, but I couldn’t go to the video arcade until I split wood with that six-pound maul. My parents wouldn’t let me watch the TV until I did my homework. I wasn’t allowed to have dessert until I cleaned my plate.

I elbowed my way back up the ramp and into the lobby. I called the captain’s room. No answer. Barged my way back through the crowd. After this second, closer look, the girls in white looked twelve years old to me. I faced the street and stared at my phone, scrolling with my thumb. I sensed someone. He veered toward me. A clean-shaven, young man with short, dark hair. A dirty green jacket. One eyelid drooped. He held a black garbage bag in his left hand and an energy drink in the other. Dirty kicks that used to be white. He got close enough to talk.

Here we go, I thought.

Some shouts came up from the doorway to my right. The band director counted off and the brass rang off the stone towers. The pom-poms flew around. The trombones bobbed up and down. The tall players emerged from the front door and walked through the crowd like Ents through a crowd of Hobbits.

I don’t mean to be disrespectful, he said.

He was soft-spoken and I struggled to hear him over the band.

I don’t want to bother you, he said.

The band was so loud it hurt.

I’m a veteran, he said.

Every pedestrian was now blocked, so they stood and gawked. People raised more phones. Flashes. The players kept striding to the bus.

I was in Iraq, he said.

I asked, What unit were you in?

I was in Kirkuk. First Infantry Division. The Big Red One, he said.

He rattled off a series of unit names. All part of the 2003 efforts in the north. He seemed legit. I looked the units up later. He was either the real deal or an amazing liar.

The band played on. The young girls dressed in white jumped up and down and shouted at their schoolmates. Every single one of the ball players wore headphones.

He talked slowly. About 80% of normal speed. I thought, Maybe he’s drunk. He was a good six inches shorter than me. I leaned closer to hear him. No, he was just tired.

I was in the 179th Fighter Squadron, I said. I’ve been to Iraq a few times myself.

I opened my wallet and gave him some money. I watched my hands like they were someone else’s. Maybe the money would help him. Maybe it wouldn’t. Who knows? Who cares?

He said, Thanks for your service.

I could understand those words from a civilian. I didn’t understand why one veteran would say it to another. I still don’t.

We shook hands.

He drifted slowly away to another guy looking at his phone.

I looked to the right. The giants continued to wade through the tunnel of young flesh. No expressions on their faces. No acknowledgement of the crowd whatsoever.

I looked left and the man with the garbage bag talked to the guy. I saw their lips move but couldn’t hear what they said over the nearby ruckus. The guy blew him off without even looking up from his phone.

Fifty people now crowded around, smiling, pointing, and taking pictures of the stone-faced athletes. Fifty strangers who had somewhere to be were now somehow pleased to be obstructed by these tall young men and their worshippers.

I looked left. A soldier who knew the smell of the desert lifted his can to his lips, drained it, and walked slowly down the sidewalk. Alone and straight away from the sound and the light.

My phone rang in my pocket as the bus pulled away from the curb.

The captain asked, You coming? I’m with the van on the other side of the band.

I see you now, I said into the phone.

The trumpet players and the girls with the flowing hair turned their backs amid the dying echoes of the music.

I no longer care what people do to distract themselves. Have at it. But those pedestrians pointing their phones at the giants should’ve done their chores before they smiled at the pageantry.

This isn’t about my inferiority complex anymore.

This is about when you deserve to relax.

All you people turn around and look at the guy from The Big Red One.

All you people haven’t cleaned your plate yet.

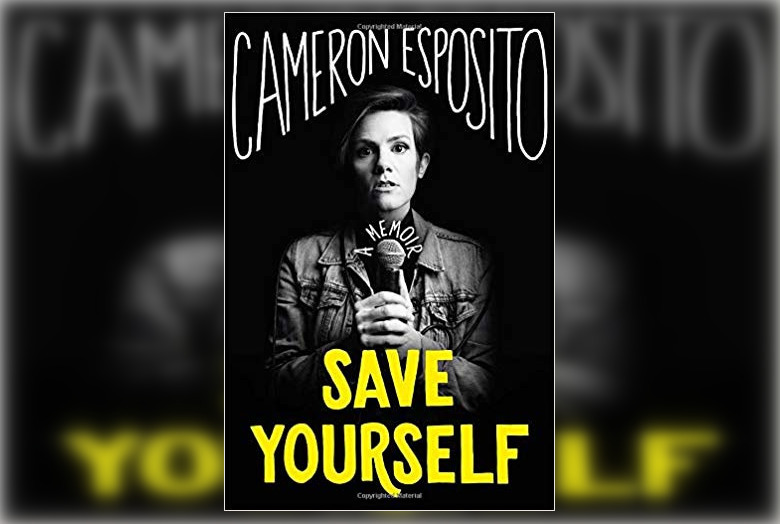

Eric Chandler is a husband, father, and pilot who cross-country skis as fast as he can in Duluth, Minnesota. His book of poetry Hugging This Rock (Middle West Press, 2017) was just released November 1, 2017. He is the author of two other books: a collection of outdoor essays called Outside Duluth and a novella titled Down In It. His writing has appeared in Northern Wilds, Grey Sparrow Journal, The Talking Stick, Flying Magazine, Sleet Magazine, The Thunderbird Review, O-Dark-Thirty, Line of Advance, The Deadly Writers Patrol, and Aqueous Magazine, to name a few. He’s also a veteran of both the US Air Force and the Minnesota Air National Guard. He flew 145 combat missions and over 3000 hours in the F-16. He’s a member of Lake Superior Writers, the Outdoor Writers Association of America, and the Military Writers Guild.