Review by Carla Stockton

“Thus I take my leave of my lost city. Seen from the ferry boat in the early morning it no longer whispers of fantastic successful and eternal youth. . . All is lost save memory.” (“My Lost City,” July, 1932)

F. Scott Fitzgerald characters are quirky, multilayered creatures who stumble through their stories, as Fitzgerald stumbled through his own, as though they are caught in the glare of oncoming life. The characters’ experiences, reflections of the author’s observations and reminiscences, resound with a fury rarely captured in adaptations, and, until Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, I wasn’t sure they ever could be. Luhrmann succeeded in capturing their wide-eyed foundering with remarkable sensitivity, and yet after I saw the film, I found myself outcast among my friends and respected colleagues.

Many of the people I admire most in the world hated the film; I loved it. And I loved it for precisely the reasons that they hated it: for the garish glitz and the dizzying 3D. Since the people I know tend to be vehement in their hatred and intolerant toward dissent – “I’ll un-friend anyone who says they like the film,” one man wrote on his Facebook wall – I kept my mouth shut. Until now.

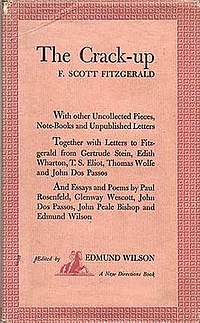

Now, having recently discovered and read The Crack-Up, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s own quasi-memoir (which is actually a collection of Fitzgerald’s essays edited to form a memoir by Edmund Wilson), I can speak with impunity. I am vindicated.

Baz Luhrmann represents Fitzgerald in ways that reveal an astute grasp of the demons that plagued the author, who was dead of the complications of alcoholism by age 44. The over-sharp focus, the bilious camera moves and the lurid scenes that turned so many critics and viewers off, actually encapsulate the Gatsby I had perceived even as a young reader the first time I encountered the novel, the one I tried to convey to my students when I taught it years later. The Crack-Up validates my sense of Fitzgerald in general and of the circumstances surrounding Jay Gatsby’s existence in particular.

The Fitzgerald of the essays is deafened by the noise of his flapper-dominated dreams and nightmares. “The whole golden boom was in the air – its splendid generosities, its outrageous corruptions and the tortuous death struggle of the old America in prohibition. All the stories that came into my head had a touch of disaster in them . . . In life these things hadn’t happened yet, but I was pretty sure living wasn’t the reckless, careless business people thought – this generation just younger than me” (from “Early Success,” October 1937). Luhrmann’s hothouse soundtrack sensibility for The Great Gatsby and its implied bling — with Beyonce, Jay-Z and Kanye West, the xx and other shouting, whining artists standing in as Gatsby’s background singers—captures Fitzgerald’s inner dissonance, the screaming “offensive, the realization of having cracked” that surely kept him awake nights.

One very close friend of mine complained that the film was too cynical, that she remembered the novel as a depiction of the innate naïveté of America in the jazz age, of the reckless innocence that preceded the stock market collapse of 1929 (Gatsby was published in 1925). But Gatsby was written when Fitzgerald was 33, long after he had lost his wide-eyed wonder, long after he discovered that “there was a rankling indignity, that to me had become almost an obsession, in seeing the power of the written word subordinated to another power, a more glittering, a grosser power.” (“Early Success,” 1937), and the title character retains the façade of innocence, but he is as jaded as the author himself. Gatsby embodies Fitzgerald’s notion that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. Life was something you dominated if you were any good.” (“The Crack-Up,” 1936).

Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jay Gatsby, criticized by many for being too calculating, too removed, was exactly the Gatsby I inferred from the book, an alter-ego of the novelist himself, who wrote, in the title essay, “Though the present writer was not so entangled. . . it was his nervous reflexes that were giving way – too much anger and too many tears. . . . I lived in a world of inscrutable hostiles and inalienable friends and supporters. But now I wanted to be absolutely alone and so arranged a certain insulation . . . .”

Gatsby may hope that he can begin again, recapture the love and the “iridescence of the beginning of the world” Fitzgerald himself saw in New York in the 1920’s. But he knows he is caught in the reality of the giddy, gilded pretenses of the upper class life he has created out of airy trifles. He lives in Fitzgerald’s “real dark night of the soul and it is always three o’clock in the morning, day after day. At that hour the tendency is to refuse to face things as long as possible by retiring into an infantile dream – but one is continually startled out of this by various contacts with the world.” (“Pasting it Together,” 1936).

In his 1937 essay “Early Success,” Fitzgerald muses over the young man he was, who arrived in New York from the Midwest with a theatrical dream of the future in his heart and cardboard soles in his shoes, and he imagines that “. . . for an instant I had the good fortune to share his dreams. I who had no more dreams of my own.” He imagines himself creeping up on his younger self, visiting him at a time when “he and I were one person, when the fulfilled failure and the wistful past were mingled in a single gorgeous moment – when life was literally a dream.” I admit to having wept when I read that, realizing that already in 1925, at the age of 29, Fitzgerald was already that lost soul; he was Jay Gatsby.

Baz Luhrmann got it. Somehow he has become intimate with Fitzgerald’s dark victory.

———-

Carla Stockton is a first year student in the Creative Writing M.F.A. Program at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.