Mark Rothko committed suicide at his apartment in New York, one year before the Rothko Chapel was completed in 1970. His health was declining – complications from smoking and drinking – and he was refusing medical advice. It was during his last days that Rothko was working on several large works for a postmodern art structure commissioned by the de Menil family in Houston, Texas. Even in poor health, Rothko was committed to the project, even going as far as to jerry-rig the lights in his studio on East 69th Street to mimic the natural light in Texas. He stated that it would be his single most important artistic statement. Due to the curvature of the earth, the light in New York would never truly mimic the light of Houston, Texas—shadows don’t work like that—so this was a fruitless endeavor. That failed recreation of light is a small example of a great masters decline that colors the experience I have when standing in front of his work. It all seems so pointless at times. So nothing. I often wonder where Rothko placed his work on the chapel in the grand scheme of his career. It’s beautiful, a testament to what abstract and postmodern art can create, but it’s also isolated, not really in conversation with Rothko’s’ work as a whole. Also, while the Chapel is visited by roughly 55,000 people a year, Rothko’s works are more frequently appreciated in museums such as the MET, The Guggenheim, MoMA, and the Tate Gallery, to name a few.

As mentioned, it’s his suicide and his certainty of the chapel’s far ranging impact that lingers in my mind. I’m attracted to the assuredness of an artist completing a final act, knowing it will be their conclusion. Rothko’s classic pieces—large swaths of color—are a meditation on form and style and meaning. They ask each viewer to step past preconceived notions they have regarding what a painting has to depict. Through large squares of color, Rothko invites personal reflection, once stating that each person should have a personal relationship with his work—that his main is to cultivate a two way relationship. In this way, the Chapel is his conclusion, not only of technical works, but also of his own personal ideas on art. The paintings for the chapel are typical large canvas, but they are mostly black, devoid of any color.

Yet, here I am, standing with my girlfriend, her sister, and her mother on a humid Houston summer morning waiting for the Rothko Chapel to open. We mill around a patio that pretends to be quaint. Usually, the square, marble fountain would add some refreshment and ambiance to the dull, insistent chirping of chicads and the melting wave of heat. Usually, the fountain’s centerpiece, a Barnett Newman statue called Broken Obelisk, can be observed in the round, giving people something to contemplate before stepping inside the chapel. But today the fountain is dry; the obelisk is off somewhere for restoration, and the Chapel is still closed. So, we wait, painfully and bored. We’re from Los Angeles—that is to say, we’re impatient and used to places opening on time—but the Rothko Chapel is running late.

We quip about how the humidity makes people run slow, how we’ve been operating in a fog since flying into Texas. Three days ago? Four? I’ve lost track. What have we done during that time? The weather breeds bugs that bite us, the humidity corrodes the metal obelisks, the Chapel’s opener is, presumably, off somewhere getting iced coffee. All around us the nothingness drones on and we hate the heat, the local animal life, and the opener for being late.

We inspect the outside of the Chapel. It’s an irregular octagon, according to my girlfriend’s mom, an architect, and by the time we complete a lap around it the time is 10:11 AM, the glass door clicks open, and we’re let inside. Is it worth the wait? We’re dubious. The benches preceding the main chapel are lined with religious texts of all kinds. Non-denomination taken to the extreme.The Quran, the Torah, the Bible in fifteen or so different languages, pamphlets on Confucianism and Taoism, Hindu Vedas, symbols and runes so foreign and ancient that they mean nothing to me. I pick up the Tibetan Book of the Dead because it’s the one I can most easily make into a joke without offending anyone and walk inside the chapel proper.

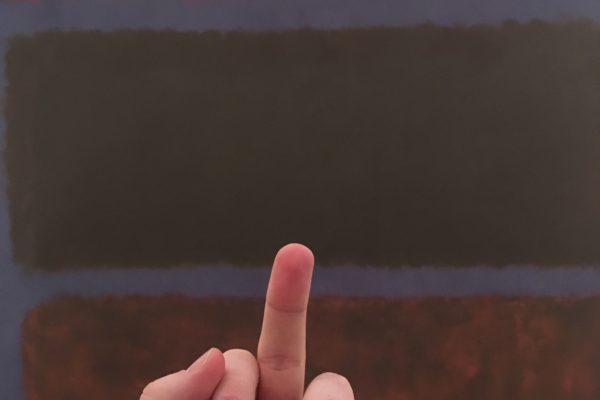

Fourteen large, black, stereotypical late-Rothko works line the walls. We meander around, sitting here and there on the benches or pillows and examine the three large triptychs of black—endless black. Except that after further examination the black is chaotic with reds and browns and charcoal greys. One triptych lines up perfectly so to create a single giant monolith of black canvas. The other two triptychs have their outer two paintings offset so the symmetry of the room—the energy in the room—is just a tad off, a nod to chaos, adding to some beautiful ominous feeling. Additionally, single, large paintings hang on the walls, interspersed between the larger works.

We admire these paintings for a long time, sometimes we stand very close, so it is only through our peripheral vision that we remain connected to the outside world. Then we sit back, far away from the walls. At a distance, the paintings stretch over us like a shadow or a massive black tidal wave that’s at its highest, its apex, its peak of destructive powers; it is going to consume us all in a mass of tar and we’ll sink and become one with the deep.

I feel humbled. I discard my Tibetan Book of the Dead, which now seems like a silly token that I brought in to make light of this situation. I am being rude, I am making a mockery of this place, this place my girlfriend labeled pretentious. Although now that I think about it, it may have been me that labeled it pretentious, and why do I do that? At the Chapel, I’m not having an experience I would call religious. (The only religious person I’ve ever known was my Grandma, a “Lutheran”). However, Rothko’s works stare back at me. When I was younger I paddled out into the ocean very far. Storms, as they do in the late summers of Florida, roll in quite suddenly, and on this instance I was engulfed in water that looked as if it was boiling and the sky and the water became one dark mass. I do not often think about this time, but I carry it with me. I feel this memory mixing with the overwhelming experience of the Rothko Chapel. Sitting here, on a bench in the chapel, a weight sinks into me—sinks into my heart and I do not feel like I will soon stop carrying it.

♠

I find the older I am the more things around me come to an end. Funerals, sure, an easy comparison to draw, but also, experiences, friendships, relationships, all end. In these absences are things anew. No canvas a complete black. No end without a beginning. This is not the same as my morbid interpretation at the Chapel a year ago, while confronted with waves upon waves of large black paintings. Now, when I think about the paintings I saw at the Chapel, it’s a cheeriness, a hopefulness that I see now. Giant windows of color. I subscribe to that Rothko idea. Last summer, when my now ex-girlfriend and I took our leave of the chapel we sat in the air conditioned car for a long time in total silence. “I love Rothko,” she said. “I do, too,” I said. It’s been almost two years since I’ve visited the Rothko Chapel—who knows? There’s is a possibility I’ll never return—but now I can actually say I do. I do.♦