“Our silver is also called the White Bride, lying on the bed. Together with her husband, the Crimson King, who rises from the coffin, they enter Mary’s bath, in which through primeval Dampness they will conceive a Son, who will surpass his parents in all things. Look, here the Father upon his throne devours his Son and profusely sweats, to which sweat the Ancients had given the term …”

Professor Amadeus Billy shut the book with a sigh and wearily rubbed his forehead. Since breakfast, he had already been ploughing his way through the labyrinth of kings and queens, their beds, thrones, spas, and coffins and was still searching in vain for a single intelligible sentence, a single reed, of which he could in this threatening and unintelligible darkness grab hold. What he would have given to be able to continue in his research, but fate had decided otherwise, and so there was nothing left but to steel oneself with patience, open the alchemical folio again, and continue reading.

x x x x x

The laboratory of experimental chemistry was a forgotten place, hidden in the labyrinth of university corridors. Only a few remembered that they had once walked past the peeling door with a brass plate, upon which there was now only faintly engraved:

Prof. A. Billy, PhD

There was no reason to remember it. For several years now, there hadn’t been any interest in experimental chemistry on the part of the students, and Amadeus Billy lectured in no other subject. He did not recall his last lecture, nor his last students. He avoided his university colleagues. He sat isolated in his laboratory and wholly dedicated himself to bizarre experiments, the proceedings and results of which he scrupulously recorded in yellowed ledgers.

He would arrive around nine in the morning and would leave the university when the clock on the façade of the building struck midnight. He lived alone; nobody waited for him at home, and he often did not speak to anyone for days. Only with the cleaning woman, who came once weekly to mop the floor in the laboratory, was it necessary to converse shortly and politely. She was a quiet woman with a headscarf and a sad expression with which she always entertained him when she complained about her rags falling apart in her hands because of all those things she had to wipe off his floor.

Many a time, Amadeus Billy prepared to bring her a dozen new rags, but he did not know how to dress up the thing so that she might not interpret the gift in her own way. So it never happened.

The days passed by, one after the other, and the yellowed ledgers filled with more meticulous records of consistently stranger experiments. That is, until the day when, on the threshold of his laboratory, Amadeus Billy found the new issue of The Experimental Chemist and an oblong, brown envelope with the Chancellor’s seal.

Amadeus Billy acknowledged with pleasure that The Experimental Chemist had printed his article about extracting nickel from olive oil. However, there were five gross grammatical mistakes, which again spoiled his delight. In a bad mood, he opened the brown envelope and read: “Due to reasons of entirely insufficient results of your laboratory’s scientific work, this facility has been denied the requested funds from the university’s budget for next year.”

Amadeus Billy’s knees buckled, and he had to sit down. Once more, he read the crushing news, which he held in his shaking hand, and afterwards he looked desperately around the laboratory: silent and brooding, slightly dusty, but nothing in the world was as dear to him. Why, only here could he conduct the experiments with which he consecrated his life. Yet a mere laboratory was not enough. It was necessary to buy the constantly utilized raw materials; laboratory glassware also had to be replenished, burners as well, but what mainly …

Why, with this letter flickered out every chance to obtain the gold electrode which was supposed to be the future pride of his workplace and which he wanted to acquire out of the allotted money above all else. The sheet fell from his hands. The golden specter vanished, and he remained alone with his laboratory.

Not for long. Which is to say that the cleaning woman opened the door just then, set the bucket on the floor, and wearily sighed when she beheld that the floor was even worse off than usual.

Amadeus Billy roused himself with a jerk, gathered the letter from the floor, and stood.

“Good morning,” he greeted her with a forced smile. “Is it Wednesday again? Time’s just flying by, isn’t it?” He tried for levity but was unsuccessful.

The cleaning woman silently embarked upon mopping and only with an occasional, loud sigh indicated that the old professor apparently didn’t intend to have any compassion for hard-working people and intentionally poured everything on hand to the floor. Amadeus Billy was, as always, on pins and needles because of her presence; in the oppressive silence, he paced the laboratory and got in the cleaning woman’s way. Today, he decided to dispense with everything quickly. “I’m not going to be here now. I’ve got work elsewhere,” he announced to her and walked out of the room.

“What’s this here?” he heard her voice just as he was closing the door and, in that moment, with a chill, realized that the previous day he had spilled corrosive sodium hydroxide, which still lay in a narrow crevice under the laboratory table. He stopped, but didn’t know what to say and felt awkward. He closed the door.

Still, he deliberated on how to warn the cleaning woman, yet the painful scream, which presently rang out from the laboratory, was incontrovertible proof that a warning was unnecessary all the same. With hasty steps, he withdrew.

He roamed the corridors aimlessly for a while, examined the display cases next to classrooms, and contemplated what he could get done and procure while his place was being cleaned.

He set out in the direction of the Chancellor’s office.

x x x x x

“Ahh, Professor Billy,” the Chancellor raised his eyebrows in badly feigned surprise when Amadeus Billy entered through the large doors. “What have you got for me?”

“I … I received your letter today, Chancellor,” answered Amadeus Billy as he laid the sheet on the desk. The Chancellor took hold of it and perfunctorily scanned the lines. “This is all correct. I have nothing more that I could add to it,” he said and put the letter aside on the corner of the desk.

“But that’s not possible! I need that money! I can’t get anywhere without it, Chancellor, after all I have to maintain the laboratory and its operating expenses …”

“And the operating expenses for your laboratory are decidedly not commensurate with its results!” The scowling Chancellor interrupted harshly. “The sum you requested is somewhere between double and triple of the usual financial expenditures of the other laboratories. That is quite a bit of money given the published results!”

The Chancellor pulled an older issue of The Experimental Scientist from the pile of papers on his desk and angrily waved it in Amadeus Billy’s face.

“A strip of paper is soaked in a solution of ferrous sulfate, exposed to the effects of ammonia vapors, and then is dried in tobacco smoke in order to prevent the iron oxide from reverting to its original state. On the paper will settle a yellow sheet of gold, which is then dissolved in aqua regia. It is, however, not possible to subject this minute quantity of the resultant metal to a proper chemical analysis.”

The Chancellor acrimoniously closed the journal. “So, why would someone do all that? Is this what you call scientific activity, professor? I am not even talking about your ridiculous article in the latest issue! The money for your olives and tobacco smoke will decidedly be more useful elsewhere! And, besides, you would be as well!”

In a now gentler voice, he added: “Fifteen years ago a position was offered to you in the then nascent laboratory of analytical chemistry, which is the most prestigious workplace at this university today. Nobody blamed you for your refusal then. It was expected that due to your abilities and knowledge you would build up a laboratory of experimental chemistry of which our university could be proud, and which would make a name for itself in the academic world. Unfortunately, nothing like that happened. Your promising beginnings soon came to nothing, partly because of a lack of student interest in your field, for which, of course, nobody can blame you, professor; indeed, mainly it was due to your inclinations toward something, to which it is, rather than serious scientific work, apt to apply the term Alchemy! Perhaps you are sensible enough to understand that I will not finance your eccentricity! I would be glad if you were to accept a position in the analytical laboratory, although not in a leadership position this time. I am giving you seven days to deliberate. Should you decline for a second time and remain in your existing position, I advise you that I will weigh every penny before I release any funds to you! Which reminds me—I was informed that you have not yet turned in the financial statement for last year to the office. So, I ask you to do so as soon as possible. For now, I wish you a good day. And a week from today I want to know your decision!”

With this last reminder, the Chancellor leaned over the ledgers on his desk again and no longer paid Amadeus Billy any mind. Amadeus Billy, having left the letter in place, angrily vacated the office.

x x x x x

The laboratory was empty—the cleaning woman had gone—when Amadeus Billy returned. He did absolutely nothing else that day. For his research, he needed a clear head. But Damocles’ sword of threats and the necessity to make a decision clouded his mind. His scientist’s pride was offended by the Chancellor’s disdainful words about his efforts, and he was choking with rage at the memory of how his work had been termed eccentricity! The word alchemy, however, still resounded in his ears …

To accept a position in the analytical laboratory and thus join the ranks of a collective of at least five other coworkers was, for Amadeus Billy, out of the question; he had become too accustomed to being his own boss and organizing work in his own way.

Now he sat behind the desk, head in hands and submerged in thoughts.

Hours passed.

He was unaware that this book might have been here when he had left the laboratory. He stood and reached for the much-handled volume with letters embossed into a leather binding: Omina ab uno et in unum omnia. He opened the book, and a small, white card fluttered to his feet. He bent down for it.

It was all the way behind the cabinet. Maybe you were looking for it. Good day, was written on the paper, doubtless in the cleaning woman’s hand.

Odd, thought Amadeus Billy. “I had never seen this book,” he said to himself and absent-mindedly slipped it into his jacket pocket.

It was six o’clock, and it had gotten dark outside. Professor Billy locked up the laboratory, left the university, and headed home.

x x x x x

The sun stood high in the sky, and its rays painted a picture of the window frame on the white wall when Amadeus Billy woke the next day. The hands of the old alarm clock, good-naturedly ticking next to the bed, pointed to half past nine when he let his feet down the sideboard and set out to the bathroom.

During breakfast, along with memories, the previous day’s bad mood returned, and Amadeus Billy decided that he would stay home. Nobody needed him at the university, and that stuffed suit had said that he was giving him a week to decide, after all.

He slowly finished drinking his coffee and took hold of the book, which he had brought home yesterday. He ran his fingers gently over the leather spine and hesitantly opened it.

“The King’s Art of Great Work is the key to immense wealth, which will open before everyone whom God blesses …,” he read the words printed on old paper.

“Your promising beginnings soon came to nothing, thanks to your inclinations toward something which is, rather than scientific work, apt to be termed alchemy!” sounded the Chancellor’s voice, and Amadeus Billy decided abruptly: scientific work had been called alchemy, so let alchemy rescue it now. Does he, who scoops the purest gold by the fistful from the bottom of his cauldron, need money? And let this book be the key to the dim preserve of forgotten teachings which spawn golden apples!

x x x x x

Amadeus Billy studied the allegories and paintings of past adepts for the rest of the week. He often became stuck in a blind lane and no less often spent long hours by wiping the dusty layers of confusion with which the masters had covered over their shining truths for protection against the wanton curiosity of the uninitiated.

Perhaps he had been born at a fortuitous hour; perhaps he had been given a blessing meant for the few, but, at the beginning of the following week, he set out to his laboratory to flesh out the amassed knowledge and apparent secrets again and bring these to fruition in round retorts and pelicans.

The laboratory was filled with gloom and worry about the upcoming days, just as he had left it in the moment of utmost despair a few days ago.

Now, however, full of hope’s light, he began the work so that the oppressive atmosphere might dissipate as quickly as possible among the clinking glass and hissing Bunsen burners.

In duobus montibus arboribus sitis. His father is a virgin. His mother did not beget. Come here, my dearest, let us help one another and birth a new son. This is the king with a red head, black eyes, legs white—this is true mastery.

Look, he comes to you wholly prepared to beget the son, to whom there is not an equal in the whole world.

We want to go and search for the nature of the four elements, which alchemists bring forth from the world’s belly. Here are rotting bodies, which will become dirt, and this black air is the beginning of creation. For I am the blackness of white and the scarlet of white and the yellow color of red, and truthful I am and truthfully speak; I am not a liar and know that this art’s head is the raven, who during the black night and in the brightness of day flies without wings of bitterness extracted from his throat, yet the red dye will be extracted from his body and pure whiteness from his hands.

That which is over the substance is a dark cloud, vapors, and smoke, and this soil will descend to the bottom, and out of it will grow maggots of which one swallows another, for the destruction of one thing is the birth of another thing.

Look, here a new black son, whose name is Elixir, was borne. And then a dragon, who eats his own wings, will come into being.

“But how?” Amadeus Billy threw his arms up helplessly. For three days already had he toiled in the laboratory over the preparation of elixirs with no results, save strange odors contaminating the surrounding corridors, and black, viscous substances, which were impossible to wash from the laboratory glassware.

“Except that, aside from wings of wings, he may also devour his own tail,” pondered Amadeus Billy aloud, but he was not granted to say more, since the cleaning woman opened the door just then, set the bucket on the floor, and rested the broom against the wall.

“It’s Wednesday, Professor,” she looked at him apologetically and sighed. Amadeus Billy sputtered a confused apology, extinguished the burners, and left.

It had been exactly a week since he spoke with the Chancellor and, because he had wanted to know Amadeus’s decision in seven days, Professor Billy headed toward the Chancellor’s office.

x x x x x

“Ahh, Professor Billy,” the Chancellor lifted his eyebrows in a show of badly feigned surprise when Amadeus Billy entered through the large door. “What have you got for me?”

“You wanted to know my decision regarding the position in the analytical laboratory, Chancellor.”

“True, true,” the Chancellor nodded his head and tugged on his sparse beard, which sprouted from a long chin. “I believe that you have decided wisely and will accept the position. I understand, you will be a little homesick; fifteen years is fifteen years, after all, but you have decided correctly that results and teamwork are more important than sentimental adherence to something that hasn’t interested anyone for a long time, right? Well, now, Professor. I’m writing down that you accept the position in the analytical chemistry laboratory of Assistant Professor Kidd …”

“I’m not accepting!” uttered Amadeus Billy in a decisive voice.

“Excuse me?” the Chancellor blinked in surprise.

“I am not accepting the position in the analytical laboratory!” repeated Amadeus Billy, and he attempted to sound as proud as possible. “I will stay in my laboratory and continue the research. I will make do with what you provide. I will not ask for an extra nickel. You will give me what you will, but I will not give up my laboratory.” He uttered stubbornly and glanced at the Chancellor rebelliously.

That man remained quiet and measured Amadeus Billy sternly.

“Well,” he said after a moment of tense silence, “in that case, I cannot help you. What I said about money for the laboratory stands, and I will also seriously consider a change in your salary valuation, believe me, Professor, for you have until now drawn an amount disproportionately great for your scientific work, if it’s even possible to call it that. You are clear, I hope, about this unavoidable step?”

Amadeus Billy nodded and then indicated that he intended to leave.

The Chancellor released him without a single word.

x x x x x

On the way back, all this boiled in Amadeus Billy as in a smelter. On the one side the money he wouldn’t get; on the other the darned fickle dragon, refusing to devour his wings and tail; and in the middle of all this was the haughty Chancellor, who had been thrown out twice from his tenure review and was healing his own inability through revenge against more learned colleagues.

In the corridor before him appeared assistant professor Kidd and his assistant Kiddo, MS.

Amadeus Billy quickly performed an evasive maneuver through a side stairwell, since those two, not counting the Chancellor, were the last people with whom he now wanted to meet.

He aimlessly wandered the side corridors until he decided that enough time had passed for the cleaning woman to have finished her work.

He set out along the shortest route to the laboratory.

He took hold of the door handle and stepped with his right foot directly into the bucket full of slop. “Oh dear, Professor,” the good woman flung herself toward him. “I apologize so very much, I forgot about that bucket, because …,” she didn’t finish, only waved her hand over her shoulder.

Amadeus Billy did not understand what happened until the moment when he looked at the place she had indicated. He saw a pile of glass lying beneath the window, and something in him gave a great jolt. At the sight of the half-empty desk surface, there was no doubt that the glass pile was the remains of his apparatuses, with which he had worked the last three days and which had contained the isolated elixirs and other alchemical preparatives. These now flowed across the floor in colorful trickles and together formed puddles of an unpleasant, grayish shade.

“What, for God’s sake, happened?” He shouted, crushed.

“I only wanted to wipe off the table as well,” sobbed the cleaning woman, “but I caught something with my rag, and all of it fell to the floor,” she blurted out and commenced to shed heart-breaking tears.

“My elixir,” shouted Amadeus Billy and flung himself toward the broken glass at the cleaning woman’s feet. Yet, a quick glance was enough to find that all was irrevocably lost. The flagons, which remained on the desk, contained only distilled water and aqua fortis; everything else lay on the floor, and the rare extracts had long ago mixed into a worthless muck.

Amadeus Billy welled up with tears.

Suddenly, through the smudged veil of these pearls of grief, he saw something shiny among the shards. And next to it as well. He wiped his eyes on the sleeve of his lab-coat and began picking up the shards hastily. No, he was not mistaken; here he saw them clearly, after all! Small, round… and here another, and there as well! Amadeus Billy smiles and, disregarding the sharp shards, keeps on collecting.

His palm fills with sparkling grains, and he sees still more and more. Even some glass shards are covered by the precious coating, by that shining king of metals. He sees the cleaning woman’s rag lying in one of the puddles. If he remembers correctly, those rags were always black. But this one is white. A shining white as a bride’s dress, and within its folds something flashes.

And Amadeus Billy laughs whole-heartedly.

Author & Translator Bio

Author Bio

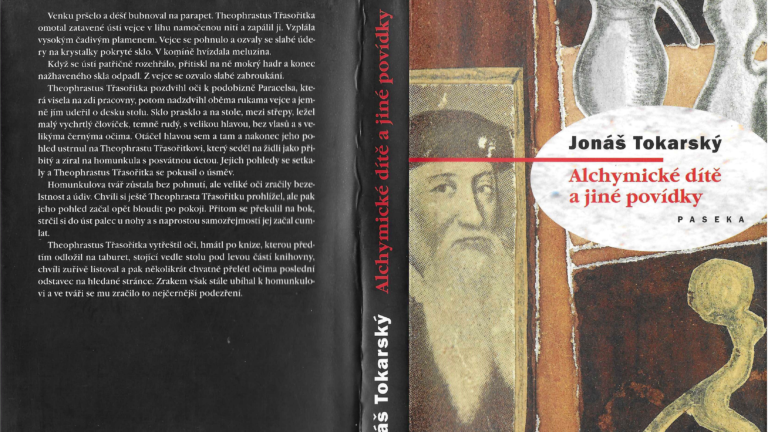

Jonáš Tokarský is an associate professor at the Nanotechnology Centre, VŠB Technical University of Ostrava, external academic staff at the Faculty of Science University Ostrava, collaborator to the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic, and research institutes within the Czech Academy of Sciences. He continues to write short stories. His influences in this genre include Gustav Meyrink, Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, Howard Phillips Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, and Daphne du Maurier, among others.

Translator Bio

Originally from Ostrava, Czech Republic, Tor Ehler lives in Denver, Colorado, where he teaches writing and literature. His work has been published in Marginalia, Reconfigurations, and Modern Language Studies, among others.